Bank Street Writer on the Apple II

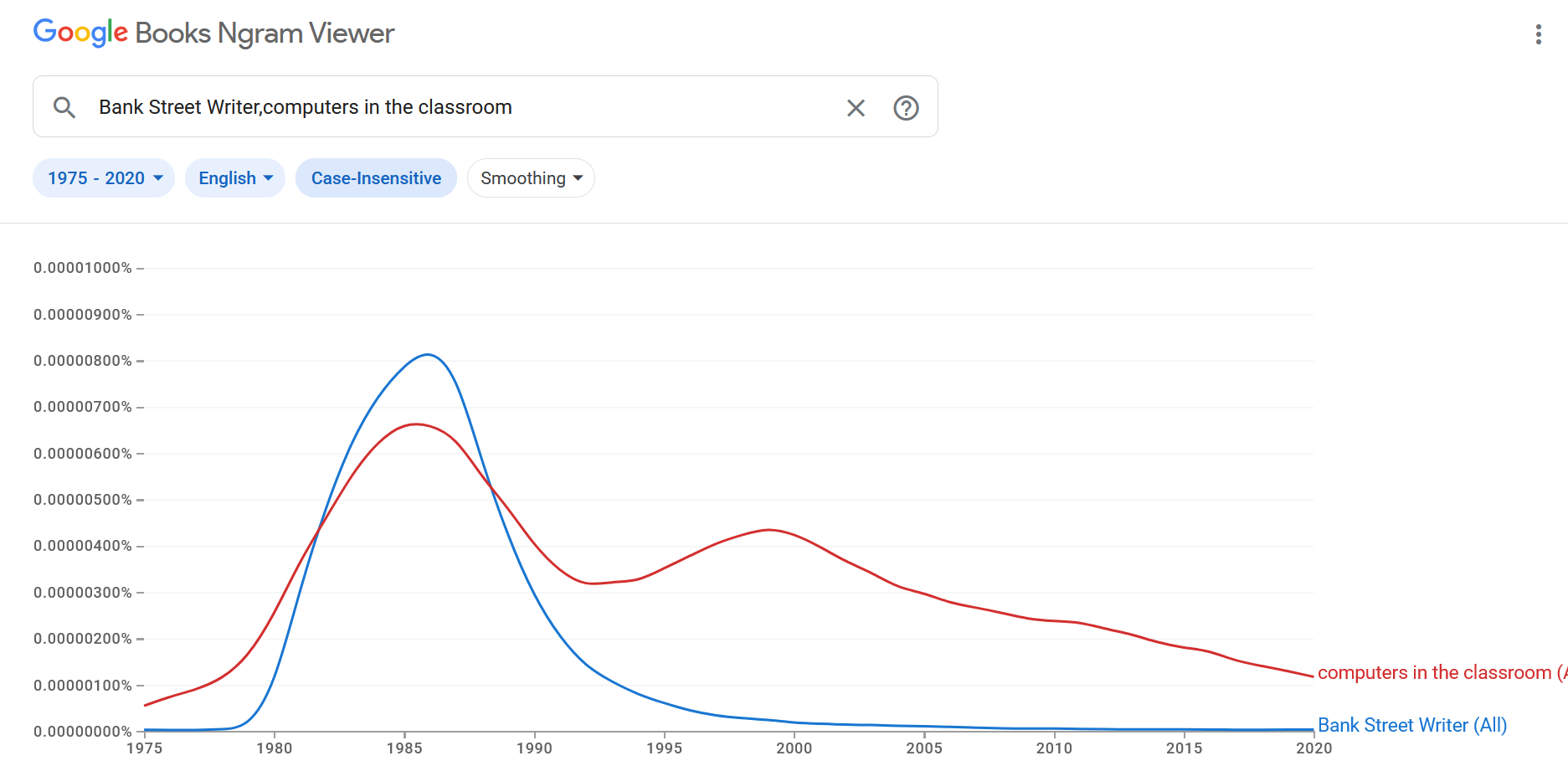

Society was once hell-bent on "computers in the classroom." The promise to transform education never materialized, but a sharp word processor did.

Stop me if you're heard this one. In 1978, a young man wandered into a Tandy Radio Shack and found himself transfixed by the TRS-80 systems on display. He bought one just to play around with, and it wound up transforming his life from there on.

As it went with so many, so too did it go with lawyer Doug Carlston. His brother, Gary, initially unimpressed, warmed up to the machine during a long Maine winter. The two thus smitten mused, "Can we make money off of this?"

Together they formed a developer-sales relationship, with Doug developing Galactic Saga and third brother Don developing Tank Command. Gary's sales acumen brought early success and Broderbund was officially underway.

Meanwhile in New York, Richard Ruopp, president of Bank Street College of Education, a kind of research center for experimental and progressive education, was thinking about how emerging technology fit into the college's mission. Writing was an important part of their curriculum, but according to Ruopp, "We tested the available word processors and found we couldn’t use any of them."

So, experts from Bank Street College worked closely with consultant Franklin Smith and software development firm Intentional Educations Inc. to build a better word processor for kids. The fruit of that labor, Bank Street Writer, was published by Scholastic exclusively to schools at first, with Broderbund taking up the home distribution market a little later.

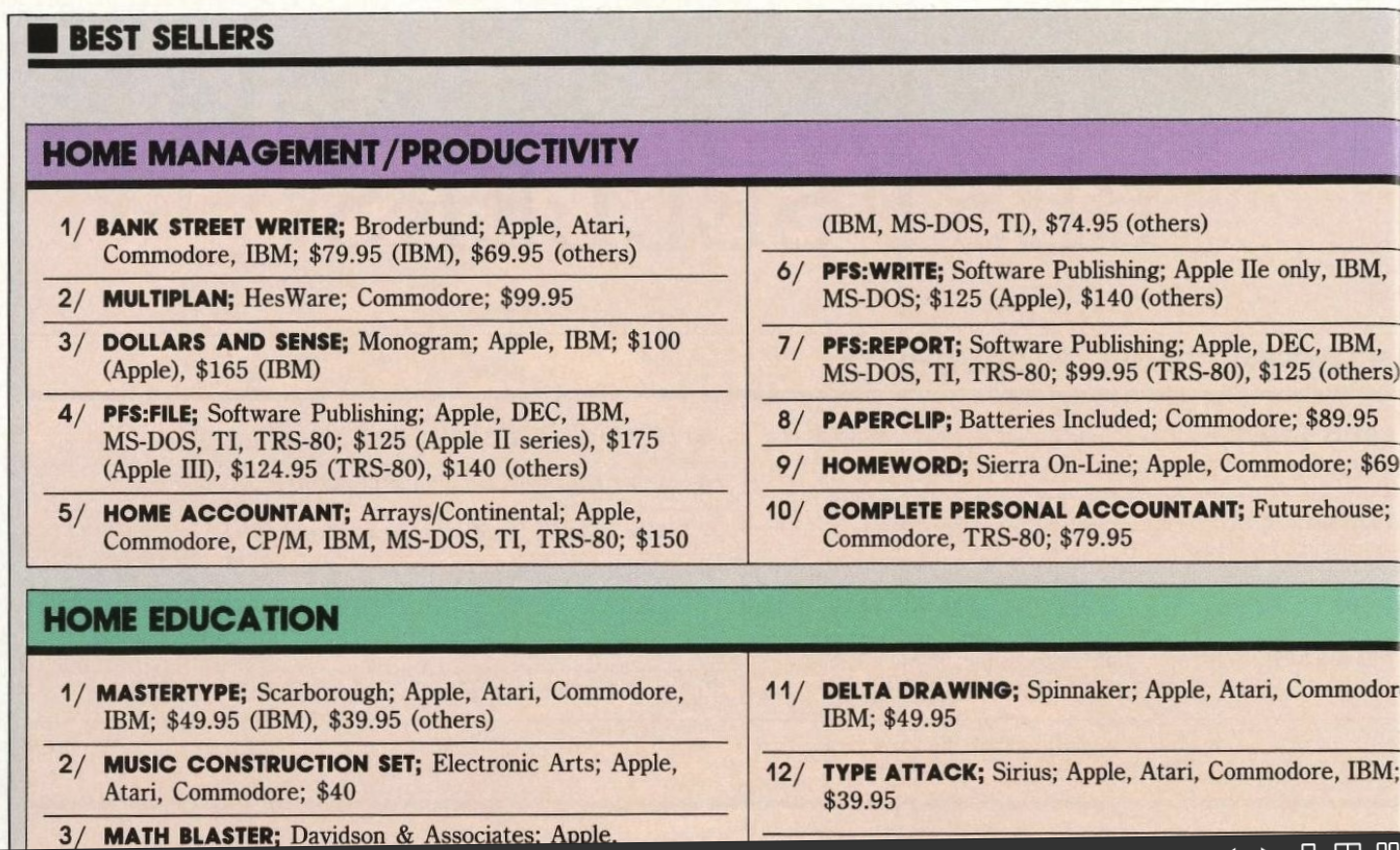

Bank Street Writer would dominate home software sales charts for years and its name would live on as one of the sacred texts, like Lemonade Stand or The Oregon Trail. Let's see what lessons there are to learn from it yet.

Historical Record

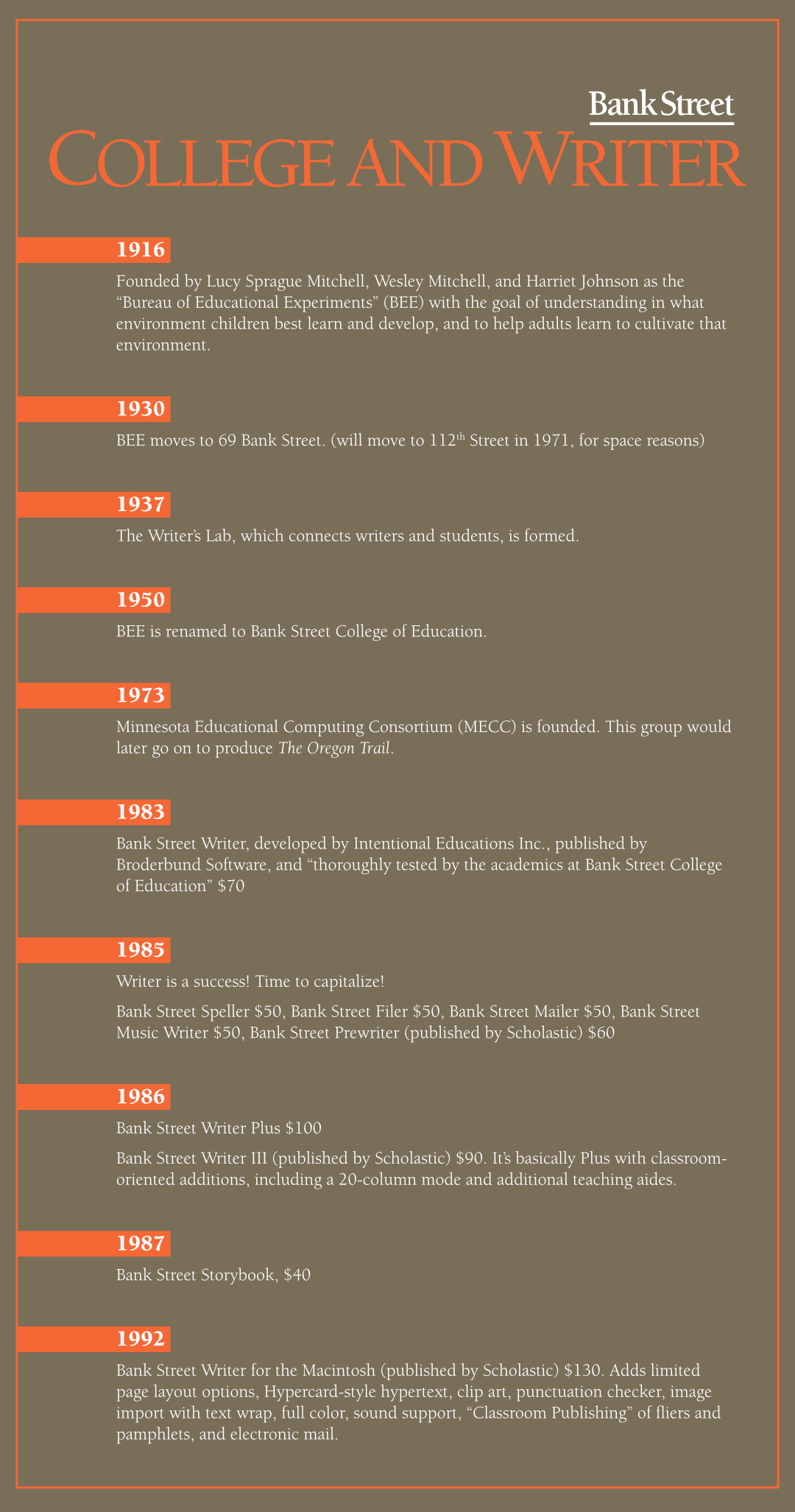

Bank Street – College and Writer Timeline

1916

Founded by Lucy Sprague Mitchell, Wesley Mitchell, and Harriet Johnson as the “Bureau of Educational Experiments” (BEE) with the goal of understanding in what environment children best learn and develop, and to help adults learn to cultivate that environment.

1930

BEE moves to 69 Bank Street. (Will move to 112th Street in 1971, for space reasons.)

1937

The Writer’s Lab, which connects writers and students, is formed.

1950

BEE is renamed to Bank Street College of Education.

1973

Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium (MECC) is founded. This group would later go on to produce The Oregon Trail.

1983

Bank Street Writer, developed by Intentional Educations Inc., published by Broderbund Software, and “thoroughly tested by the academics at Bank Street College of Education.” Price: $70.

1985

Writer is a success! Time to capitalize!

Bank Street Speller $50, Bank Street Filer $50, Bank Street Mailer $50, Bank Street Music Writer $50, Bank Street Prewriter (published by Scholastic) $60.

1986

Bank Street Writer Plus $100.

Bank Street Writer III (published by Scholastic) $90. It’s basically Plus with classroom-oriented additions, including a 20-column mode and additional teaching aides.

1987

Bank Street Storybook, $40.

1992

Bank Street Writer for the Macintosh (published by Scholastic) $130. Adds limited page layout options, Hypercard-style hypertext, clip art, punctuation checker, image import with text wrap, full color, sound support, “Classroom Publishing” of fliers and pamphlets, and electronic mail.

My Testing Rig

- AppleWin 32bit 1.31.0.0 on Windows 11

- Emulating an Enhanced Apple //e

- Authentic machine speed (enhanced disk access speed)

- 128K RAM

- Monochrome (amber) for clean 80-column display

- Disk II controller in slot 5 (enables four floppies, total)

- Mouse interface in slot 4

- Emulating an Enhanced Apple //e

- Bank Street Writer Plus

With word processors, I want to give them a chance to present their best possible experience. I do put a little time into trying the baseline experience many would have had with the software during the height of its popularity. "Does the software still have utility today?" can only be fairly answered by giving the software a fighting chance. To that end, I've gifted myself a top-of-the-line (virtual) Apple //e running the last update to Writer, the Plus edition.

Let's Get to Work

You probably already know how to use Bank Street Writer Plus.

You don't know you know, but you do know because you have familiarity with GUI menus and basic word processing skills. All you're lacking is an understanding of the vagaries of data storage and retrieval as necessitated by the hardware of the time, but once armed with that knowledge you could start using this program without touching the manual again. It really is as easy as the makers claim.

The simplicity is driven by a subtle, forward-thinking user interface.

Of primary interest is the upper prompt area. The top 3 lines of the screen serve as an ever-present, contextual "here's the situation" helper. What's going on? What am I looking at? What options are available? How do I navigate this screen? How do I use this tool? Whatever you're doing, whatever menu option you've chosen, the prompt area is already displaying information about which actions are available right now in the current context. As the manual states, "When in doubt, look for instructions in the prompt area." The manual speaks truth.

For some, the constant on-screen prompting could be a touch overbearing, but I personally don't think it's so terrible to know that the program is paying attention to my actions and wants me to succeed. The assistance isn't front-loaded, like so many mobile apps, nor does it interrupt, like Clippy. I simply can't fault the good intentions, nor can I really think of anything in modern software that takes this approach to user-friendliness.

The remainder of the screen is devoted to your writing and works like any other word processor you've used. Just type, move the cursor with the arrow keys, and type some more. I think most writers will find it behaves "as expected." There are no Electric Pencil-style over-type surprises, nor VisiCalc-style arrow key manipulations.

Manual labor

What seems to have happened is that in making a word processor that is easy for children to use, they accidentally made a word processor that is just plain easy.

"The idea of an easy-to-use word processor is not a profound notion, but it is surprising that nobody has done it before.”

- Richard Ruopp, Time Magazine interview, March 14, 1983

The basic functionality is drop-dead simple to pick up by just poking around, but there's quite a bit more to learn here. To do so, we have a few options for getting to know Bank Street Writer in more detail.

There are two manuals by virtue of the program's educational roots. Bank Street Writer was published by both Broderbund (for the home market) and Scholastic (for schools). Each tailored their own manual to their respective demographic.

Broderbund's manual is cleanly designed, easy to understand, and gets right to the point. It is not as "child focused" as reviews at the time might have you believe. Scholastic's is more of a curriculum to teach word processing, part of the 80s push for "computers in the classroom." It's packed with student activities, pages that can be copied and distributed, and (tellingly) information for the teacher explaining "What is a word processor?"

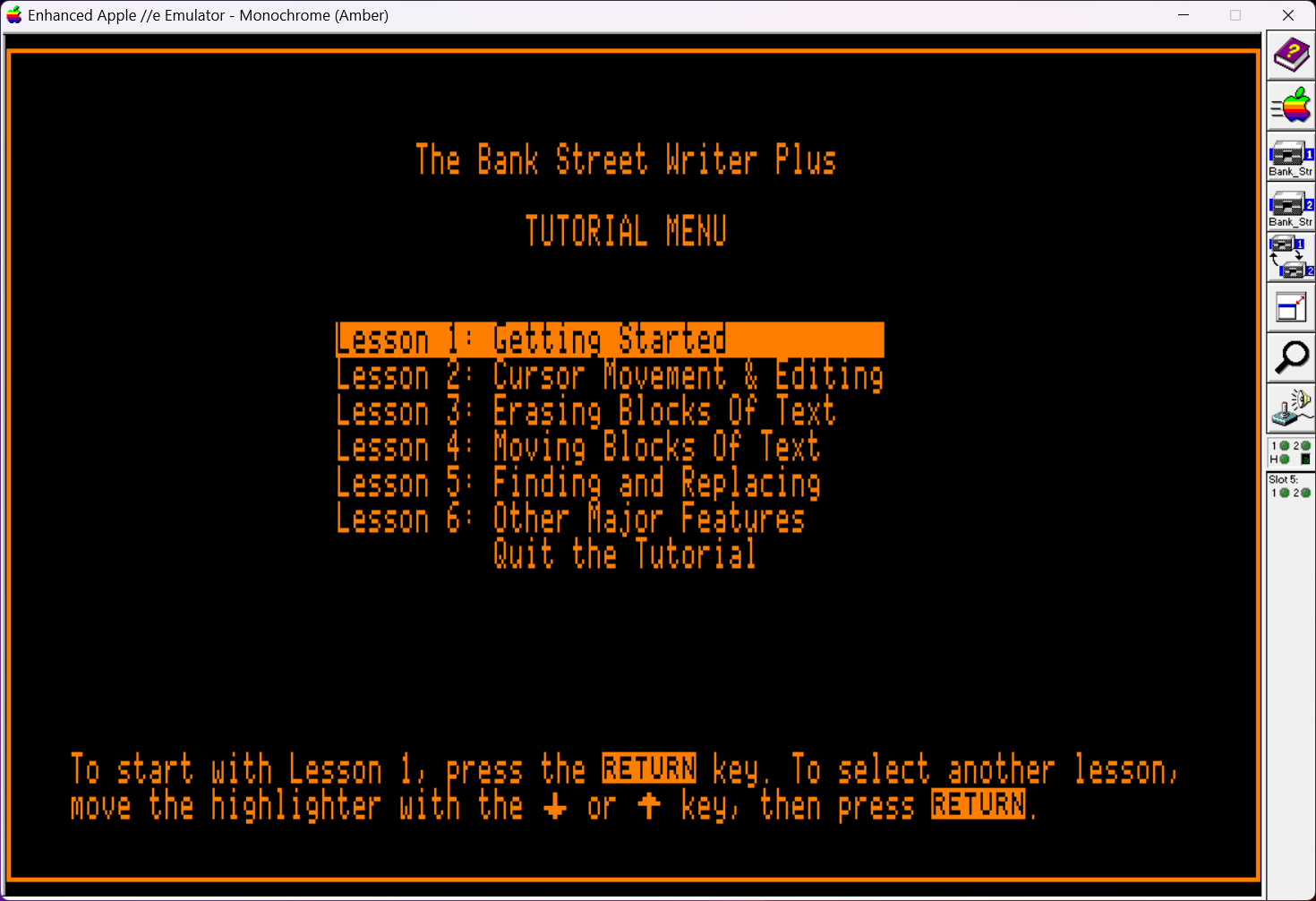

Our other option for learning is on side 2 of the main program disk. Quite apart from the program proper, the disk contains an interactive tutorial. I love this commitment to the user's success, though I breezed through it in just a few minutes, being a cultured word processing pro of the 21st century. I am quite familiar with "menus" thank you very much.

From the Scholastic manual, "Once the computer transfers your writing from its memory onto the disk, it becomes permanent. It's stored in somewhat the same way that music, for example, is stored on magnetic tape."

Growing pains

As I mentioned at the top, the screen is split into two areas: prompt and writing. The prompt area is fixed, and can neither be hidden nor turned off. This means there's no "full screen" option, for example.

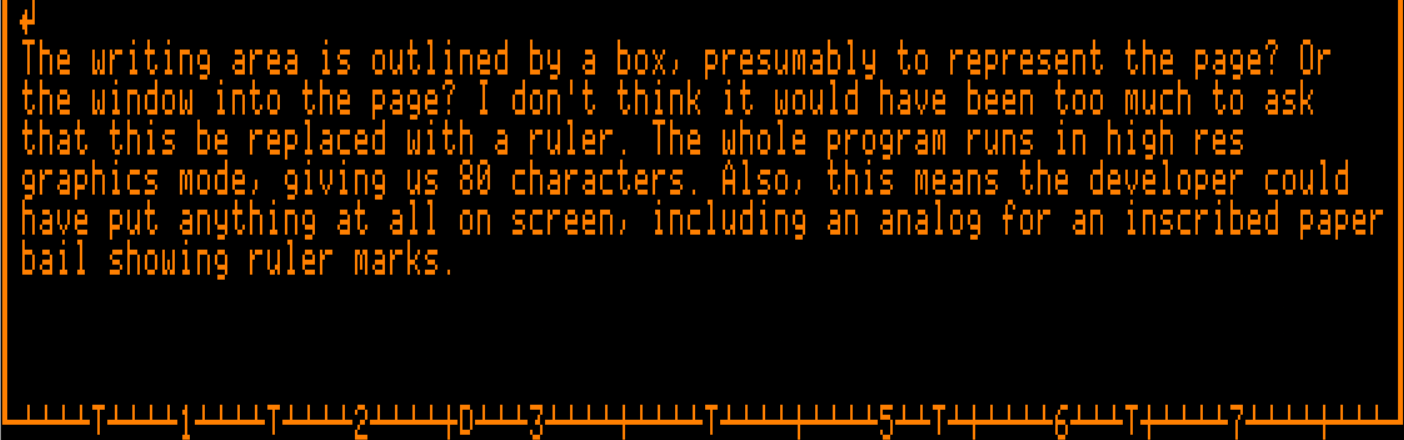

The writing area runs in high-res graphics mode so as to bless us with the gift of an 80-character wide display. Being a graphics display also means the developer could have put anything on screen, including a ruler which would have been a nice formatting helper. Alas.

Bank Street offers limited preference settings; there's not much we can do to customize the program's display or functionality. The upshot is that as I gain confidence with the program, the program doesn't offer to match my ability. There is one notable trick, which I'll discuss later, but overall there is a missed opportunity here for adapting to a user's increasing skill. Kids do grow up, after all.

You take the good, you take the bad

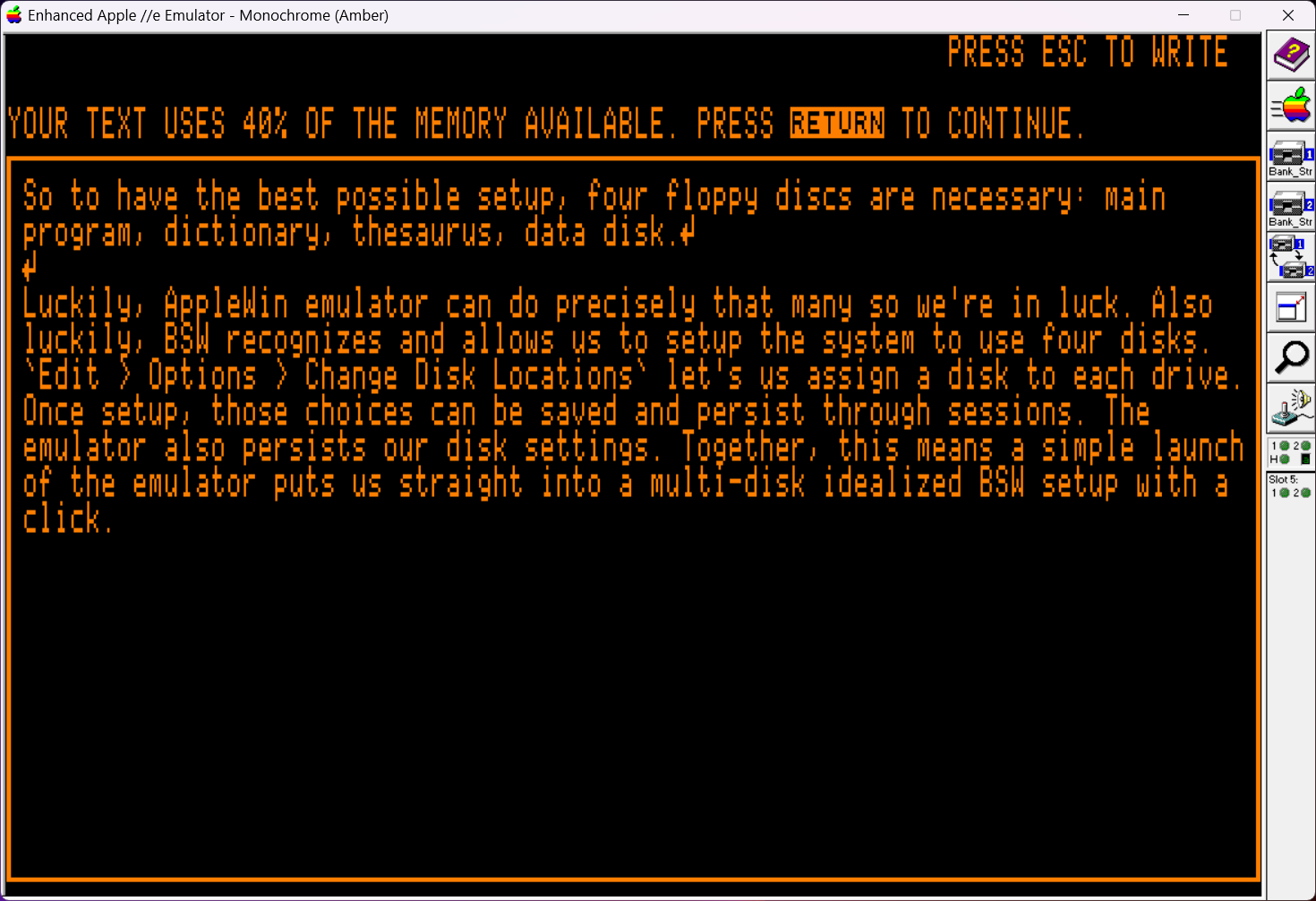

As with Electric Pencil, I'm writing this entirely in Bank Street Writer. Unlike the keyboard/software troubles there, here in 128K Apple //e world I have Markdown luxuries like ~ [] {} _. The emulator's amber mode is soothing to the eyes and soul. Mouse control is turned on and works perfectly, though it's much easier and faster to navigate by keyboard, as God intended.

This is an enjoyable writing experience.

Which is not to say the program is without quirks. Perhaps the most unfortunate one is how little writing space 128K RAM buys for a document. At this point in the write-up I'm at about 1,500 words and BSW's memory check function reports I'm already at 40% of capacity. So the largest document one could keep resident in memory at one time would run about 4,000 words max? Put bluntly, that ain't a lot.

Splitting documents into multiple files is pretty much forced upon anyone wanting to write anything of length. Given floppy disk fragility, especially with children handling them, perhaps that's not such a bad idea. However, from an editing point of view, it is frustrating to recall which document I need to load to review any given piece of text.

Remember also, there's no copy/paste as we understand it today. Moving a block of text between documents is tricky, but possible. BSW can save a selected portion of text to its own file, which can then be "retrieved" (inserted) at the current cursor position in another file. In this way the diskette functions as a memory buffer for cross-document "copy/paste." Hey, at least there is some option available.

Adult education

Flipping through old magazines of the time, it's interesting just how often Bank Street Writer comes up as the comparative reference point for home word processors over the years. If a new program had even the slightest whiff of trying to be "easy to use" it was invariably compared to Bank Street Writer.

Likewise, there were any number of writers and readers of those magazines talking about how they continued to use Bank Street Writer, even though so-called "better" options existed. I don't want to oversell its adoption by adults, but it most definitely was not a children-only word processor, by any stretch. I think the release of Plus embraced that more mature audience.

In schools it reigned supreme for years, including the Scholastic-branded version of Plus called Bank Street Writer III. There were add-on "packs" of teacher materials for use with it. There was also Bank Street Prewriter, a tool for helping to organize themes and thoughts before committing to the act of writing, including an outliner, as popularized by ThinkTank. (always interesting when influences ripple through the industry like this)

Of course, the Scholastic approach was built around the idea of teachers having access to computers in the classroom. And THAT was built on the idea of teachers feeling comfortable enough with computers to seamlessly merge them into a lesson-plan. Sure, the kids needed something simple to learn, but let's be honest, so did the adults.

NOUN + Computer = NOUN of the Future!

There was a time when attaching a computer to anything meant a fundamental transformation of that thing was assured and imminent. For example, the "office of the future" (as discussed in the Superbase post) had a counterpart in the "classroom of tomorrow."

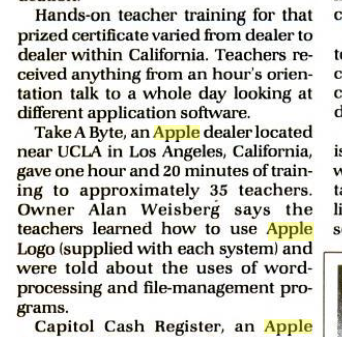

In 1983, Popular Computing said, "Schools are in the grip of a computer mania." Steve Jobs took advantage of this, skating to where the puck would be, by donating Apple 2s to California schools. In October 1983, Creative Computing did a little math on that plan. $20M in retail donations brought $4M in tax credits against $5M in gross donations. Apple could donate a computer to every elementary, middle, and high school in California for an outlay of only $1M.

Jobs lobbied Congress hard to pass a national version of the same "Kids Can't Wait" bill, which would have extended federal tax credits for such donations. That never made it to law, for various political reasons. But the California initiative certainly helped position Apple as the go-to system for computers in education. By 1985, Apple would dominate fully half of the education market.

That would continue into the Macintosh era, though Apple's dominance diminished slowly as cheaper, "good enough" alternatives entered the market. Today, Apple is #3 in the education market, behind Windows and Chromebooks.

The dog who caught the bus

It is a fair question to ask, "How useful could a single donated computer be to a school?" Once it's in place, then what? Does it have function? Does anyone have a plan for it? Come to think of it, does anyone on staff even know how to use it?

When Apple put a computer into (almost) every school in California, they did require training. Well, let's say lip-service was paid to the idea of the aspiration of training. One teacher from each school had to receive one day's worth of training to attain a certificate which allowed the school to receive the computer. That teacher was then tasked with training their coworkers.

Wait, did I say "one day?" Sorry, I meant about one HOUR of training.

It's not too hard to see where Larry Cuban was coming from when he published Oversold & Underused: Computers in the Classroom in 2001. Even of schools with more than a single system, he notes, "Why, then, does a school's high access (to computers) yield limited use? Nationally and in our case studies, teachers... mentioned that training in relevant software and applications was seldom offered... (Teachers) felt that the generic training available was often irrelevant to their specific and immediate needs."

Class-dismissed

From my perspective, and I'm no historian, it seems to me there were four ways computers were introduced into the school setting. The three most obvious were:

- At the classroom level there are one or more computers.

- At the school level there is a "computer lab" with one or more systems.

- There were no computers.

I personally attended schools of all three types. What I can say the schools had in common was how little attention, if any, was given to the computer and how little my teachers understood them. An impromptu poll of friends aligned with my own experience. Schools didn't integrate computers into classwork, except when classwork was explicitly about computers.

I sincerely doubt my time playing Trillium's Shadowkeep during recess was anything close to Apple's vision of a "classroom of tomorrow."

Careful what you wish for

The fourth approach to computers into the classroom was significantly more ambitious. Apple tried an experiment in which five public school sites were chosen for a long-term research project. In 1986, the sites were given computers for every child in class and at home.

They reasoned that for computers to truly make an impact on children, the computer couldn't just be a fun toy they occasionally interacted with. Rather, it required full integration into their lives.

Now, it is darkly funny to me that having achieved this integration today through smartphones, adults work hard to remove computers from school. It is also interesting to me that Apple kind of led the way in making that happen, although in fairness they don't seem to consider the iPhone to be a computer.

D- (see me after class)

America wasn't alone in trying to give its children a technological leg up. In England, the BBC spearheaded a major drive to get computers into classrooms via a countrywide computer literacy program. Even in the States, I remember watching episodes of BBC's The Computer Programme on PBS.

Regardless of Apple's or the BBC's efforts, the long-term data on the effectiveness of computers in the classroom has been mixed, at best, or even an outright failure. Apple's own assessment of their "Apple Classrooms of Tomorrow" (ACOT) program after a couple of years concluded, "Results showed that ACOT students maintained their performance levels on standard measures of educational achievement in basic skills, and they sustained positive attitudes as judged by measures addressing the traditional activities of schooling." Which is a "we continue to maintain the dream of selling more computers to schools" way of saying, "Nothing changed."

In 2001, the BBC reported, "England's schools are beginning to use computers more in teaching - but teachers are making "slow progress" in learning about them." Then in 2015 the results were "disappointing, "Even where computers are used in the classroom, their impact on student performance is mixed at best."

Informatique pour tous, France 1985: Pedagogy, Industry and Politics by Clémence Cardon-Quint noted the French attempt at computers in the classroom as being, "an operation that can be considered both as a milestone and a failure."

Computers in the Classrooms of an Authoritarian Country: The Case of Soviet Latvia (1980s–1991) by Iveta Kestere, Katrina Elizabete Purina-Bieza shows the introduction of computers to have drawn stark power and social divides, while pushing prescribed gender roles of computers being "for boys."

Teachers Translating and Circumventing the Computer in Lower and Upper

Secondary Swedish Schools in the 1970s and 1980s by Rosalía Guerrero Cantarell noted, "the role of teachers as agents of change was crucial. But teachers also acted as opponents, hindering the diffusion of computer use in schools."

Now, I should be clear that things were different in the higher education market, as with PLATO in the universities. But in the primary and secondary markets, Bank Street Writer's primary demographic, nobody really knew what to do with the machines once they had them.

The most straightforwardly damning assessment is from Oversold & Underused where Cuban says in the chapter "Are Computers in Schools Worth the Investment?", "Although promoters of new technologies often spout the rhetoric of fundamental change, few have pursued deep and comprehensive changes in the existing system of schooling."

Throughout the book he notes how most teachers struggle to integrate computers into their lessons and teaching methodologies. The lack of guidance in developing new ways of teaching means computers will continue to be relegated to occasional auxiliary tools trotted out from time to time, not integral to the teaching process.

"Should my conclusions and predictions be accurate, both champions and skeptics will be disappointed. They may conclude, as I have, that the investment of billions of dollars over the last decade has yet to produce worthy outcomes," he concludes.

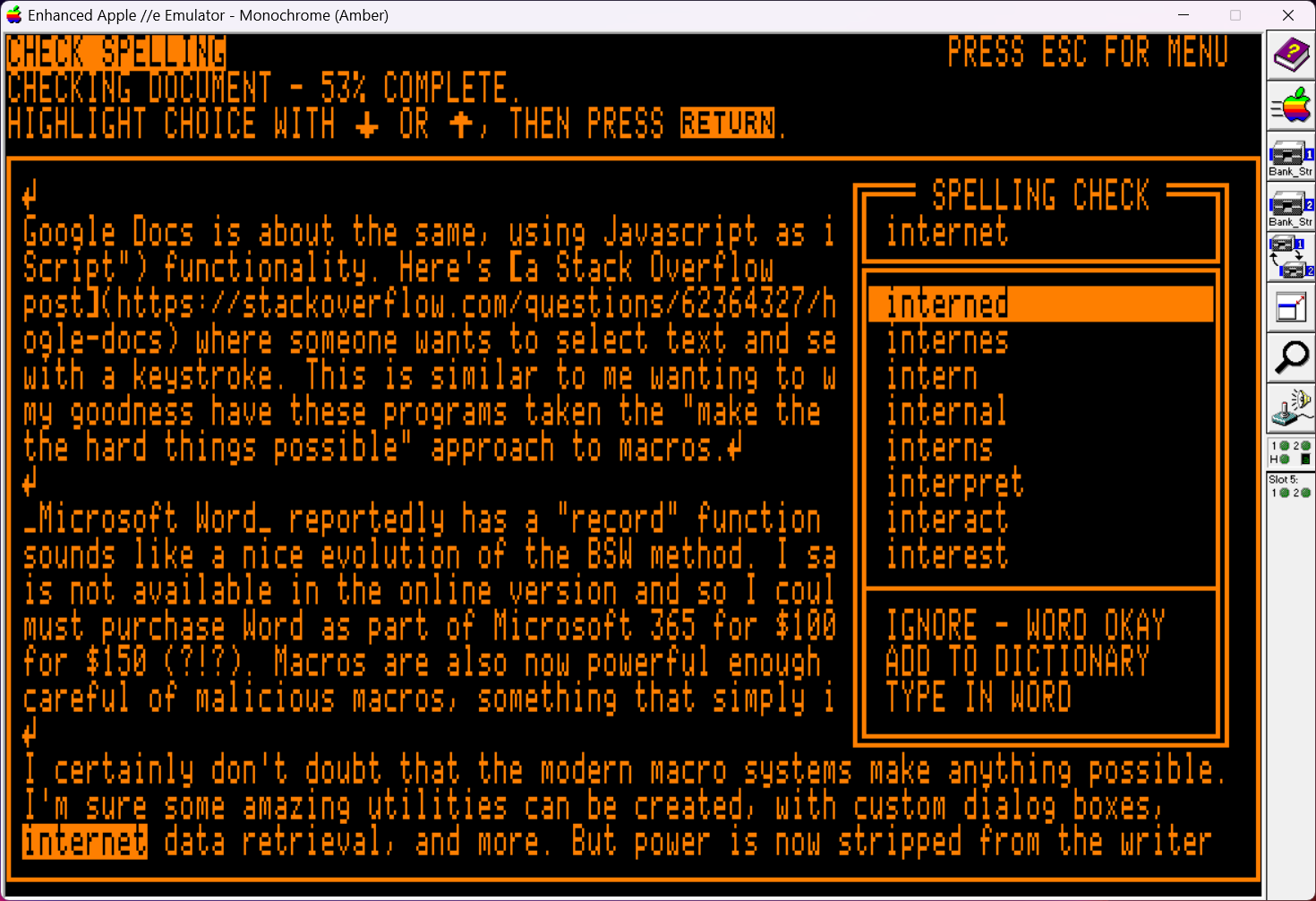

Generates statements

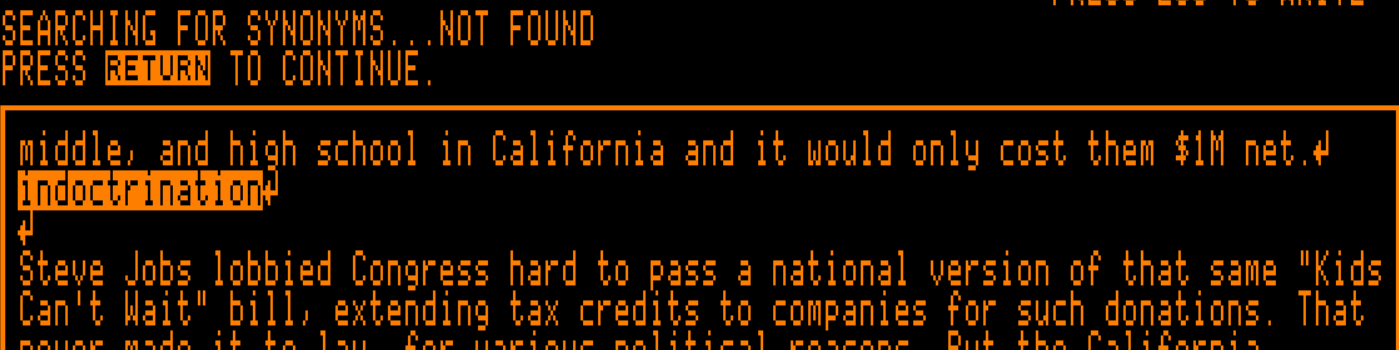

Thanks to my sweet four-drive virtual machine, I can summon both the dictionary and thesaurus immediately. Put the cursor at the start of a word and hit OpenApple + S or OpenApple + T to get an instant spot check of spelling or synonyms. Without the reality of actual floppy disk access speed, word searches are fast.

Spelling can be performed on the full document, which does take noticeable time to finish. One thing I really love is how cancelling an action or moving forward on the next step of a process is responsive and immediate. If you're growing bored of an action taking too long, just cancel it with ESC; it will stop immediately. The program feels robust and unbreakable in that way.

There is a word lookup, which accepts wildcards, for when you kinda-sorta know how to spell a word but need help. Attached to this function is an anagram checker which benefits greatly from a virtual CPU boost. But it can only do its trick on single words, not phrases.

Teenagers Testaments

Power bank

Earlier I mentioned how little the program offers a user who has gained confidence and skill. That's not entirely accurate, thanks to its most surprising super power: macros.

Yes, you read that right. This word processor designed for children includes macros. They are stored at the application level, not the document level, so do keep that in mind. Twenty can be defined, each consisting of up to 32 keystrokes. Running keystrokes in a macro is functionally identical to typing by hand.

Because the program can be driven 100% by keyboard alone, macros can trigger menu selections and step through tedious parts of those commands. For example, to save our document periodically we need to do the following every time:

- Hit

ESC (bring up the menu) - Hit

F(open the File menu) - Hit

S(select Save File) - Hit

Ythree times (stepping through default confirmation dialogs)

That looks like a job for OpenApple + 1 to me.

Defining a macro to save, with overwrite, the current file. After it is defined, I execute it which happens very quickly in the emulator. Watch carefully.

Success!

If you can perform an action through a series of discrete keyboard commands, you can make a macro from it. This is freeing, but also works to highlight what you cannot do with the program. For example, there is no concept of an active selection, so a word is the smallest unit you can directly manipulate due to keyboard control limitations. It's not nothin' but it's not quite enough.

I started setting up markdown macros, so I could wrap the current word in _ or * for italic and bold. Doing the actions in the writing area and noting the minimal steps necessary to achieve the desired outcome translated into perfect macros. I was even able to make a kind of rudimentary "undo" for when I wrap something in italic but intended to use bold. This reminded me that I haven't touched macro functionality in modern apps since my AppleScript days. Lemme check something real quick.

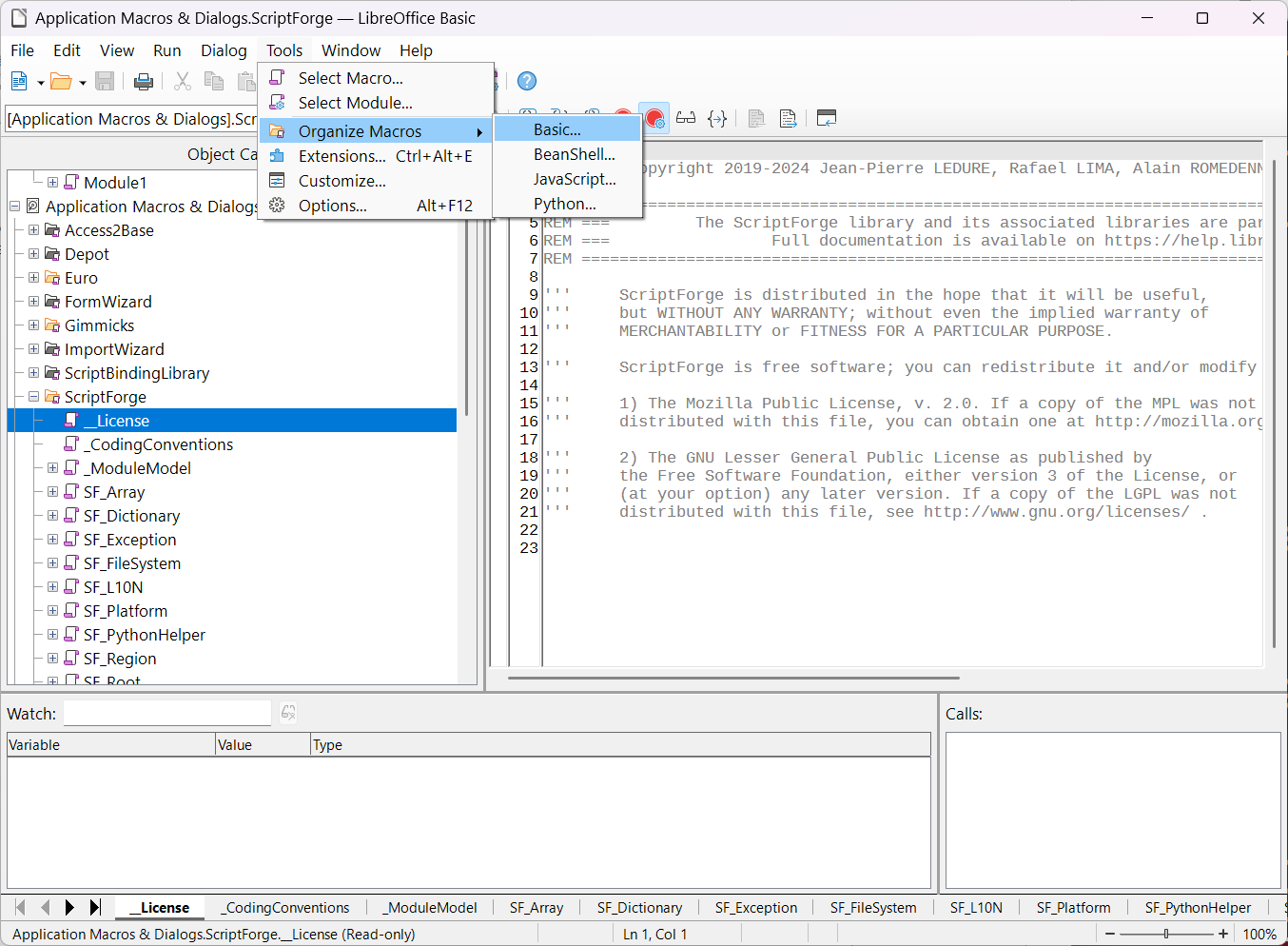

I've popped open LibreOffice and feel immediately put off by its Macros function. It looks super powerful; a full dedicated code editor with watched variables for authoring in its scripting language. Or is it languages? Is it Macros or ScriptForge? What are "Gimmicks?" Just what is going on?

Google Docs is about the same, using Javascript for its "Apps Script" functionality. Here's a Stack Overflow post where someone wants to select text and set it to "blue and bold" with a keystroke and is presented with 32 lines of Javascript. Many programs seem to have taken a "make the simple things difficult, and the hard things possible" approach to macros.

Microsoft Word reportedly has a "record" function for creating macros, which will watch what you do and let you play back those actions in sequence. (a la Adobe Photoshop's "actions") This sounds like a nice evolution of the BSW method. I say "reportedly" because it is not available in the online version and so I couldn't try it for myself without purchasing Microsoft 365.

I certainly don't doubt the sky's the limit with these modern macro systems. I'm sure amazing utilities can be created, with custom dialog boxes, internet data retrieval, and more. The flip-side is that a lot of power has been stripped from the writer and handed over to the programmer, which I think is unfortunate.

Bank Street Writer allows an author to use the same keyboard commands for creating a macro as for writing a document. There is a forgotten lesson in that. Yes, BSW's macros are limited compared to modern tools, but they are immediately accessible and intuitive. They leverage skills the user is already known to possess. The learning curve is a straight, flat line.

The tab stops here

Like any good word processor, user-definable tab stops are possible. Bringing up the editor for tabs displays a ruler showing tab stops and their type (normal vs. decimal-aligned). Using the same tools for writing, the ruler is similarly editable. Just type a T or a D anywhere along the ruler.

So, the lack of a ruler I noted at the beginning is now doubly-frustrating, because it exists! Perhaps it was determined to be too much visual clutter for younger users? Again, this is where the Options screen could have allowed advanced users to toggle on features as they grow in comfort and ambition.

From what I can tell in the product catalogs, the only major revision after this was for the Macintosh which added a whole host of publishing features. If I think about my experience with BSW these past two weeks, and think about what my wish-list for a hypothetical update might be, "desktop publishing" has never crossed my mind.

Write on

Having said all of that, I've really enjoyed using it to write this post. It has been solid, snappy, and utterly crash free. To be completely frank, when I switched over into LibreOffice, a predominantly native app for Windows, it felt sluggish. Bank Street Writer feels smooth and purpose-built, even in an emulator.

Features are discoverable and the UI always makes it clear what action can be taken next. I never feel lost nor do I worry that an inadvertent action will have unknowable consequences. The impression of it being an assistant to my writing process is strong, probably more so than many modern word processors. This is cleanly illustrated by the prompt area which feels like a "good idea we forgot." (I also noted this in my ThinkTank examination)

I cannot lavish such praise upon the original Bank Street Writer, only on this Plus revision. The original is 40-columns only, spell-checking is a completely separate program, no thesaurus, no macros, a kind of bizarre modal switch between writing/editing/transfer modes, no arrow key support, and other quirks of its time and target system (the original Apple 2).

Plus is an incredibly smart update to that original, increasing its utility 10-fold, without sacrificing ease of use. In fact, it's actually easier to use, in my opinion than the original and comes just shy of being something I could use on a regular basis. Bank Street Writer is very good!

But it's not quite great.

Sharpening the Stone

Ways to improve the experience, notable deficiencies, workarounds, and notes about incorporating the software into modern workflows (if possible).

Emulator Improvements

- I find that running at 300% CPU speed in AppleWin works great. No repeating key issues and the program is well-behaved. Spell check works quickly enough to not be annoying and I honestly enjoyed watching it work its way through the document. Sometimes there's something to be said about slowing the computer down to swift human-speed, to form a stronger sense of connection between one's own work and the computer's work.

- I did mention that I used a 4-disk setup, but in truth I never really touched the thesaurus. A 3-disk setup is probably sufficient.

Troubleshooting

- The application never crashed; the emulator was rock-solid.

Getting Your Data into the Real World

- CiderPress2 works perfectly for opening the files on an Apple ][ disk image. Files are of

.binfile extension, which CiderPress2 tries to open as disassembly, not text. Switch "Conversion" to "Plain Text" and you'll be fine.

What's Lacking?

- This is a program that would benefit greatly from one more revision. It's very close to being enough for a "minimalist" crowd. There are four, key pieces missing for completeness:

- Much longer document handling

- Smarter, expanded dictionary, with definitions

- Customizable UI, display/hide: prompts, ruler, word count, etc.

- Extra formatting options, like line spacing, visual centering, and so on.

- For a modern writer using hyperlinks, this can trip up the spell-checker quite ferociously. It doesn't understand, nor can it be taught, pattern-matching against URLs to skip them.

Fossil Record