CAD-3D on the Atari ST

Historical "what ifs" are fun. What if IBM adopted CP/M over DOS? What if Atari delivered their TT line on time, becoming Hollywood's SFX king?

There are wizards among us who can bend hardware like a Uri Geller spoon to perform tricks thought impossible. Bill Budge springs to mind, with Steve Wozniak calling Pinball Construction Set the "greatest program ever written for an 8-bit machine." A pinball physics simulation, table builder, paint program, software distribution system, and more, driven by one of the first point-and-click GUIs, all in 48K on an Apple 2.

Likewise, Bill Atkinson seemed able to produce literal magic on the Macintosh's 68000 processor. Even when he felt a task were impossible, when pushed he'd regroup, rethink, and come back with an elegant solution. QuickDraw and HyperCard are legendary, not just in what they could do, but in how they did it.

Meanwhile, over on the Atari ST, Tom Hudson was producing a steady string of minor miracles. With CAD-3D, he both pushed the machine beyond what many thought possible, while also creating something that had its users drooling at the prospect of advanced systems yet to come.

For the most part, the ST crowd had to wait essentially forever for machines that were up to the mathematical task. Hudson, frustrated with Atari's broken promises, and anxious to continue pushing the limits of 3D modeling and rendering, defected to DOS.

Atari would die, but Hudson's work would live and grow. You know it today as 3ds Max. Let's see how it started.

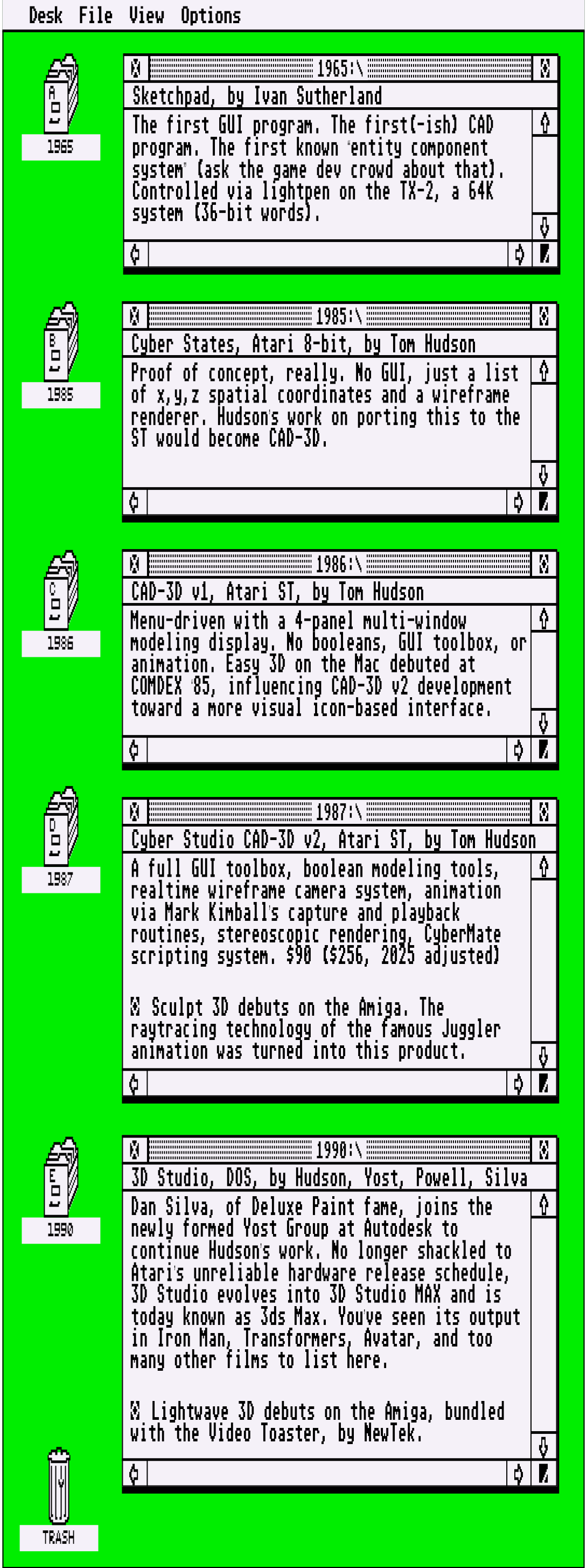

Historical Record

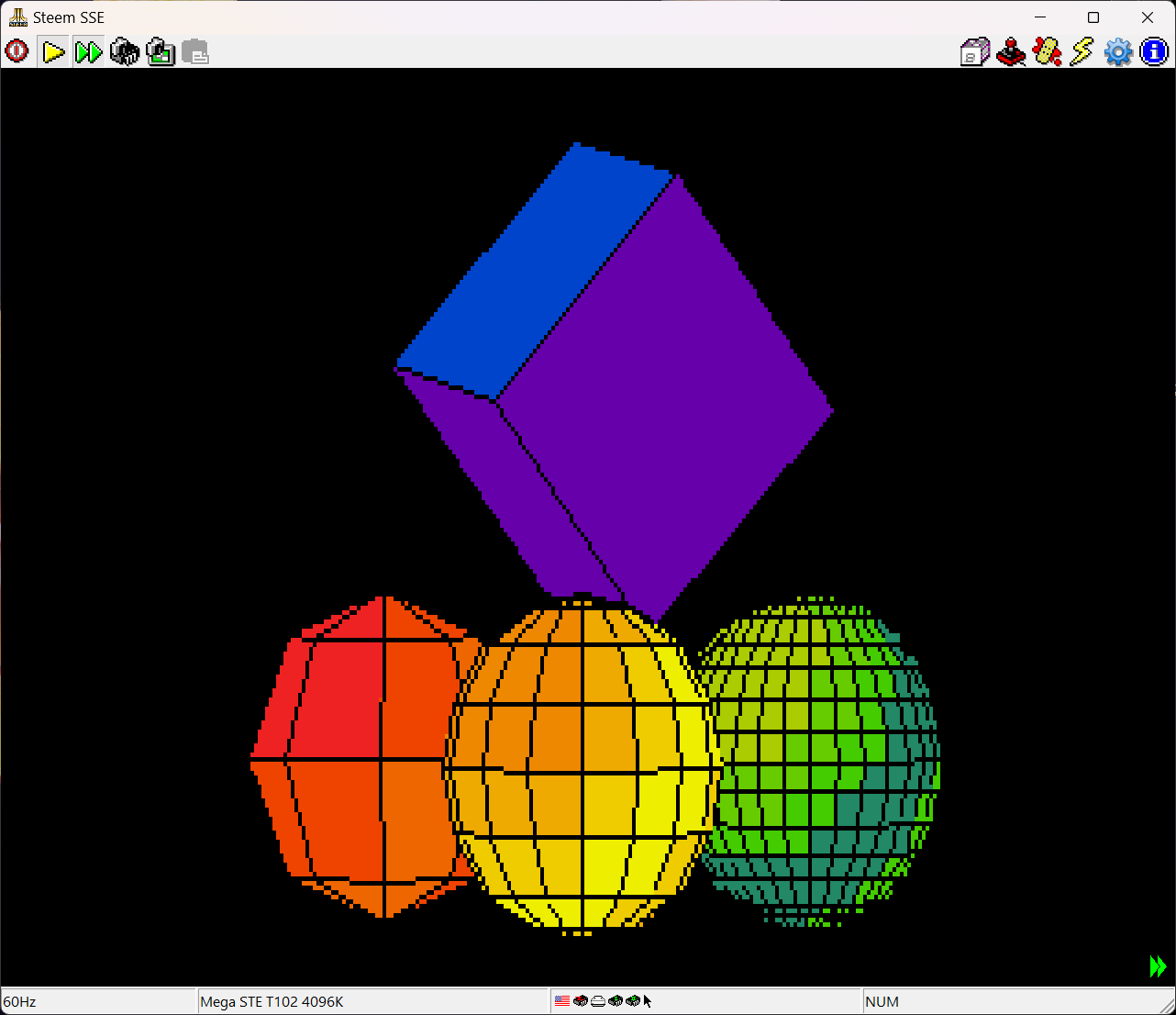

Test Rig

- Steem SSE 4.2.0 R3 64bit on Windows 11

- Emulating a MegaSTE

- 4MB RAM

- 32MHz

- TOS v.???? (it doesn't report its version number?)

- Emulating a MegaSTE

- Stereo CAD-3D v2.02

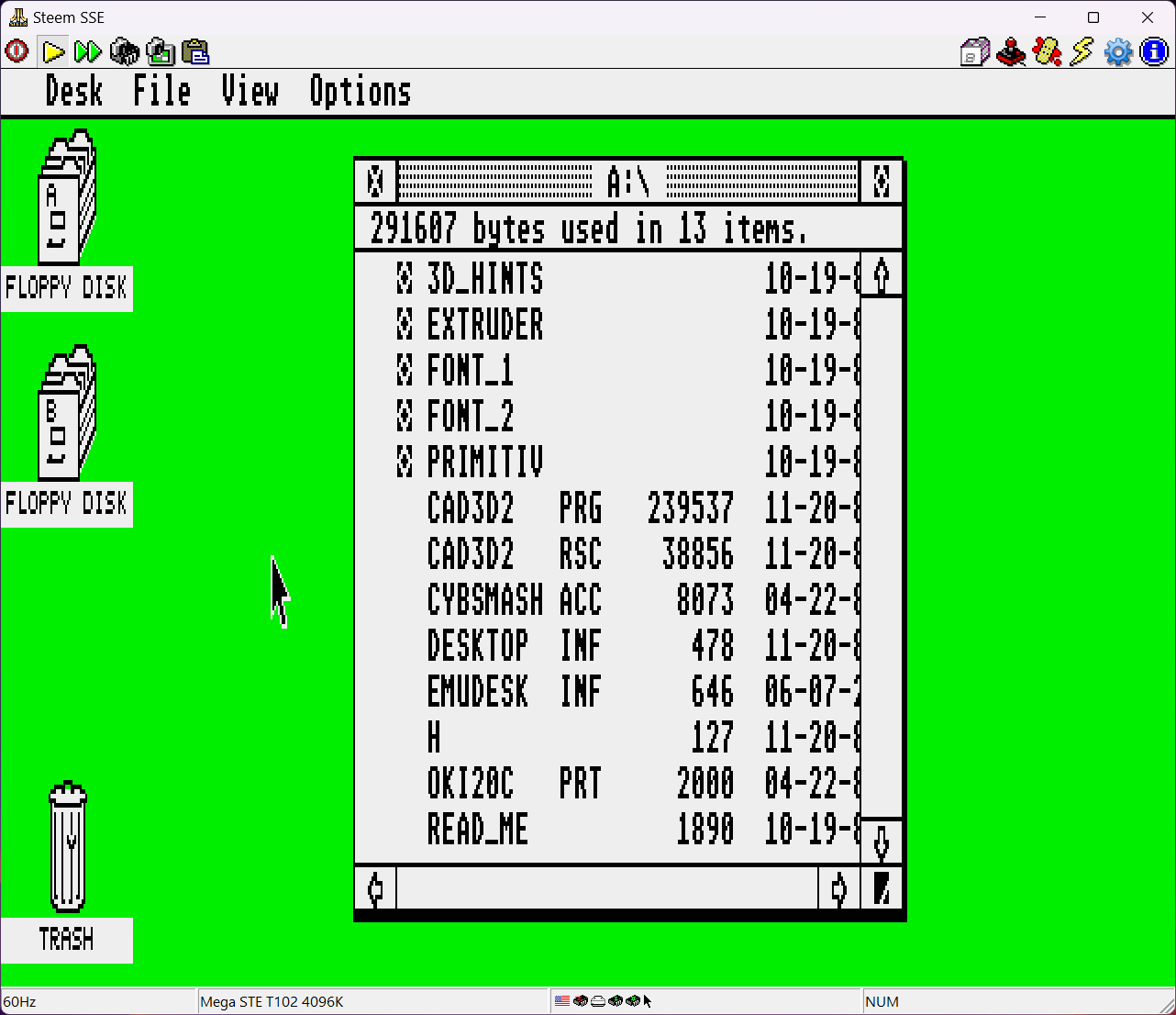

This quite literally marks my first time using an Atari ST GEM environment and software. I don't anticipate any serious transition pains coming from an Amiga/Mac background. The desktop has a cursor and a trashcan; I should be fine.

My first 3D software experience was generating magazine illustrations in Infini-D on the Macintosh around 1996. Since then, form-Z, Poser, Bryce, Strata Studio Pro, and Cinema 4D came and went; these days its just Blender. It's fair to say I have a healthier-than-average amount of experience going into CAD-3D.

Let's Get to Work

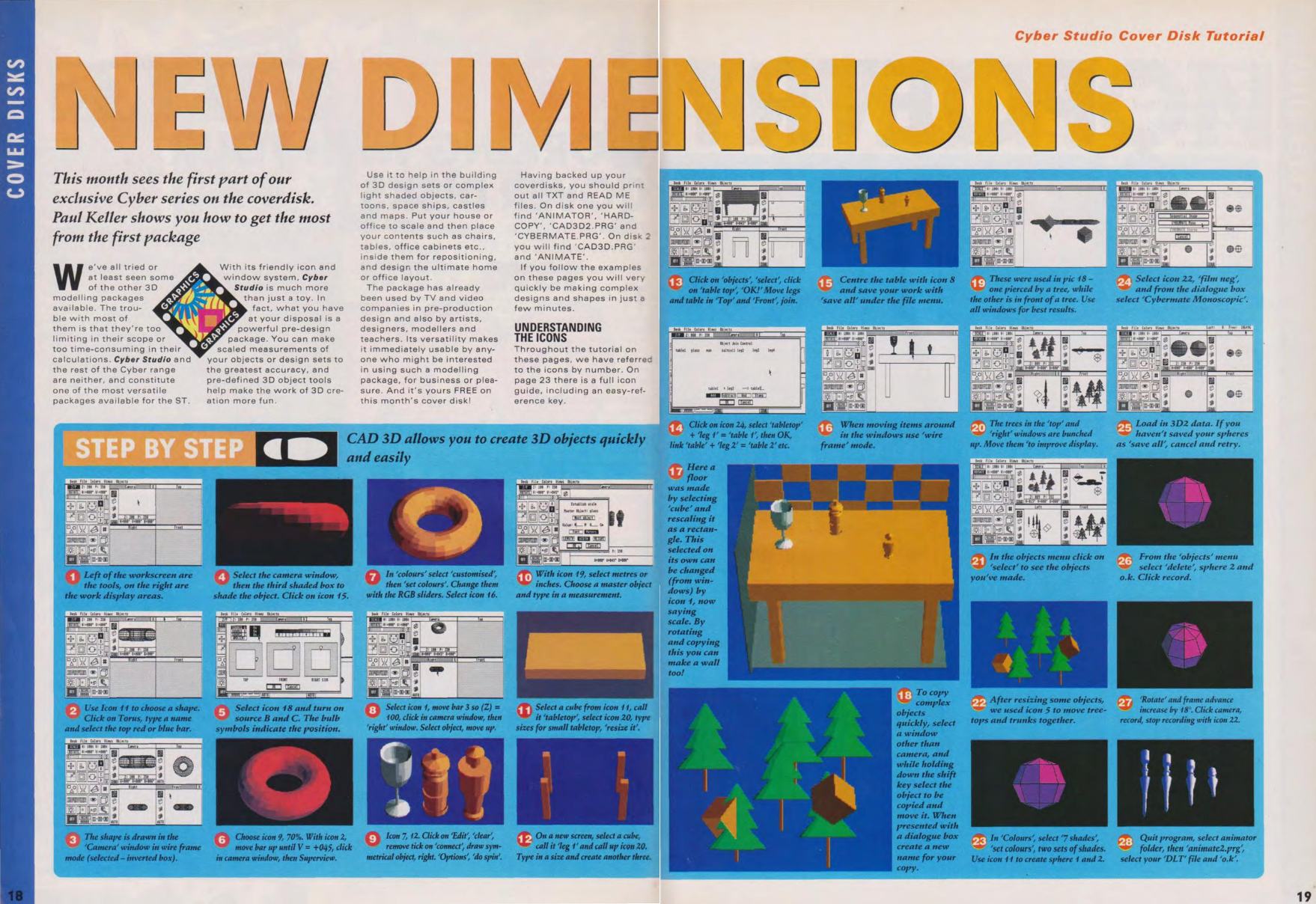

I found two tutorials worth looking into. The first is in the manual; always a good starting point.

The second is a mini-tutorial which ran in Atari ST Review, issue 8, December 1992. The cover disk, a literal 3.5" floppy disk glued to the cover, included CAD-3D 1.0 and 2.0 on it. As far as I can tell, it was the full featured software, not stripped-down "demos." A special offer in the magazine gave readers a discount on ordering the manual for £34 (about $50 US, $115 adjusted for 2025). Those suckers could have saved a bunch of money if they'd waited 30 years like I did.

The Atari ST emulator STEEM comes bundled with a free operating system ROM replacement called EmuTOS. At first, it seems like a nice alternative to GEM/TOS until I try to run CAD-3D.

GEM is my name, no-one else is the same

I have obtained a TOS which works. I am accepting NO follow-up questions. Upon boot, I get a desktop icon of a filing cabinet (?) for floppy disk B (??) even though I don't have a disk in that drive (???). Do I want a "blitter?"

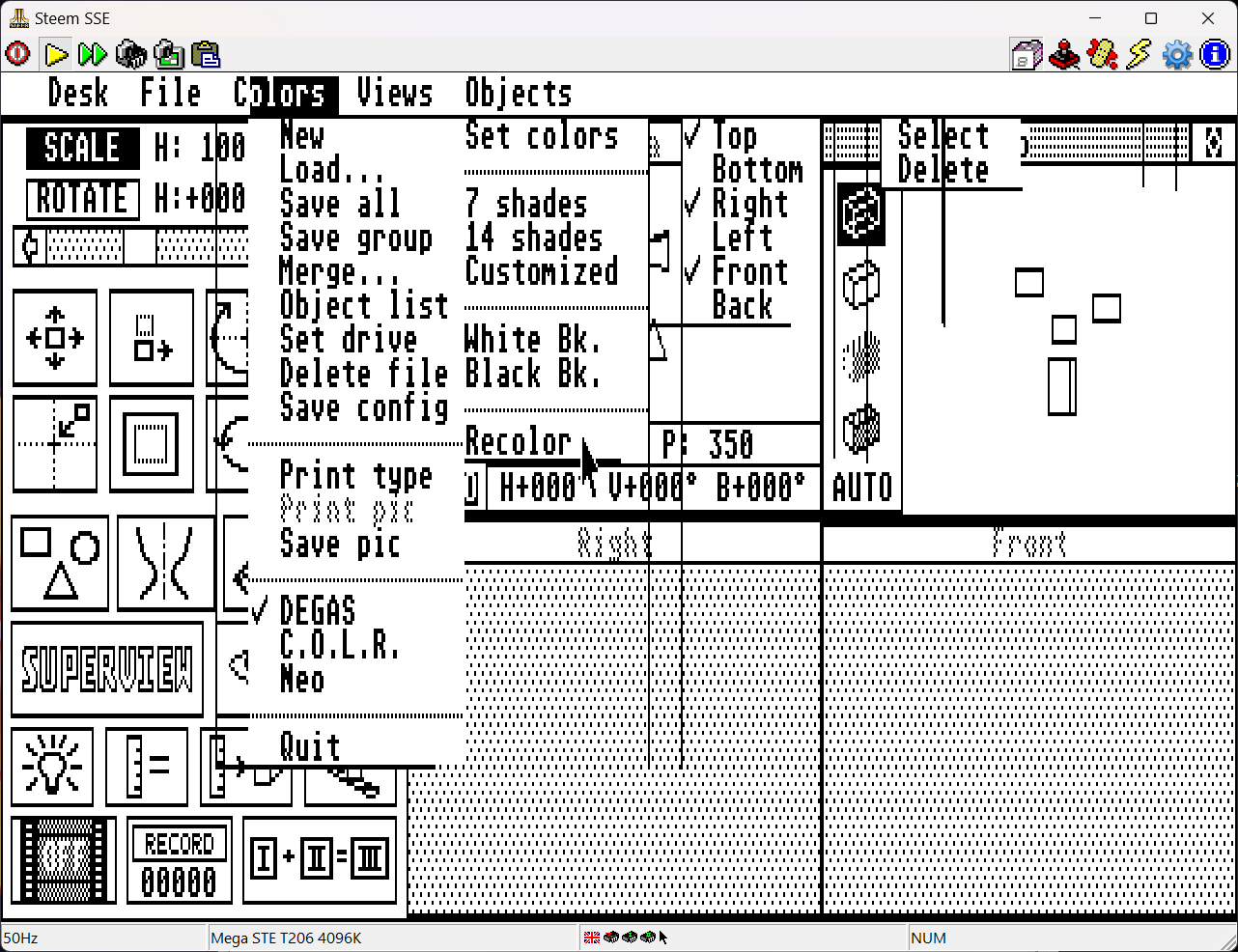

CAD-3D wants "medium resolution" (640x200), which forces GEM to draw icons and cursors at half-width, giving the interface an elongated look. Click-and-drag operations in GEM need a half-second pause to "grab" a tool, lest the cursor slide off the intended drag target. Coming from the Mac and Amiga, I get distinct parallel universe vibes.

The aspect of GEM driving me most crazy is the menu bar. It is summoned by mere cursor proximity, no click required, but requires a click outside the menu to dismiss. Inadvertent menus which cover the tool I want to interact with require an extra dismissal step so I can continue with the interface element it obscured. It's maddening.

Launching the app is relatively quick and I can kick the emulator into overdrive, which exhibits rreeppeeaattiinngg kkeeyyss. But this will be necessary from time to time, as it would for any older system trying to do the math this program demands.

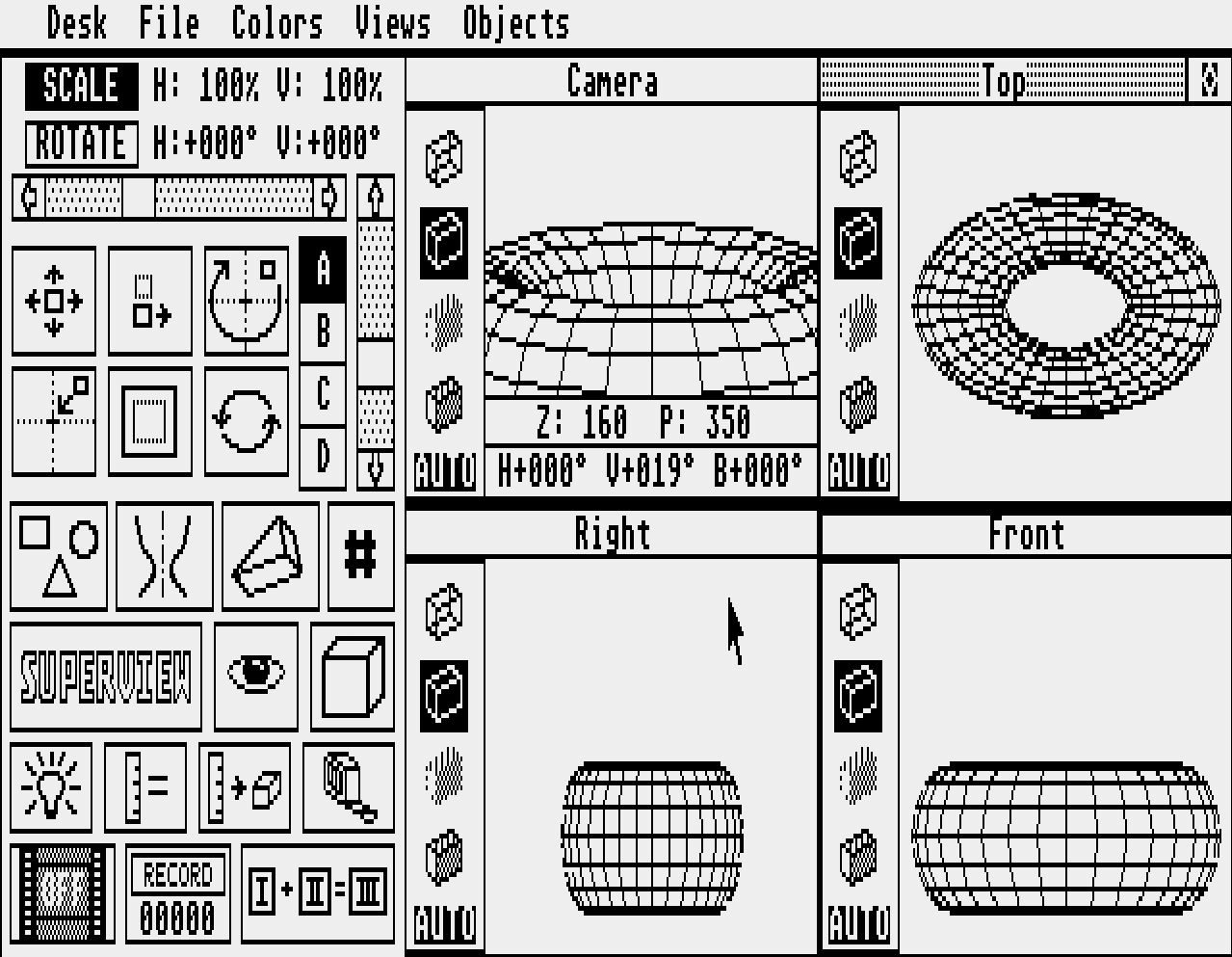

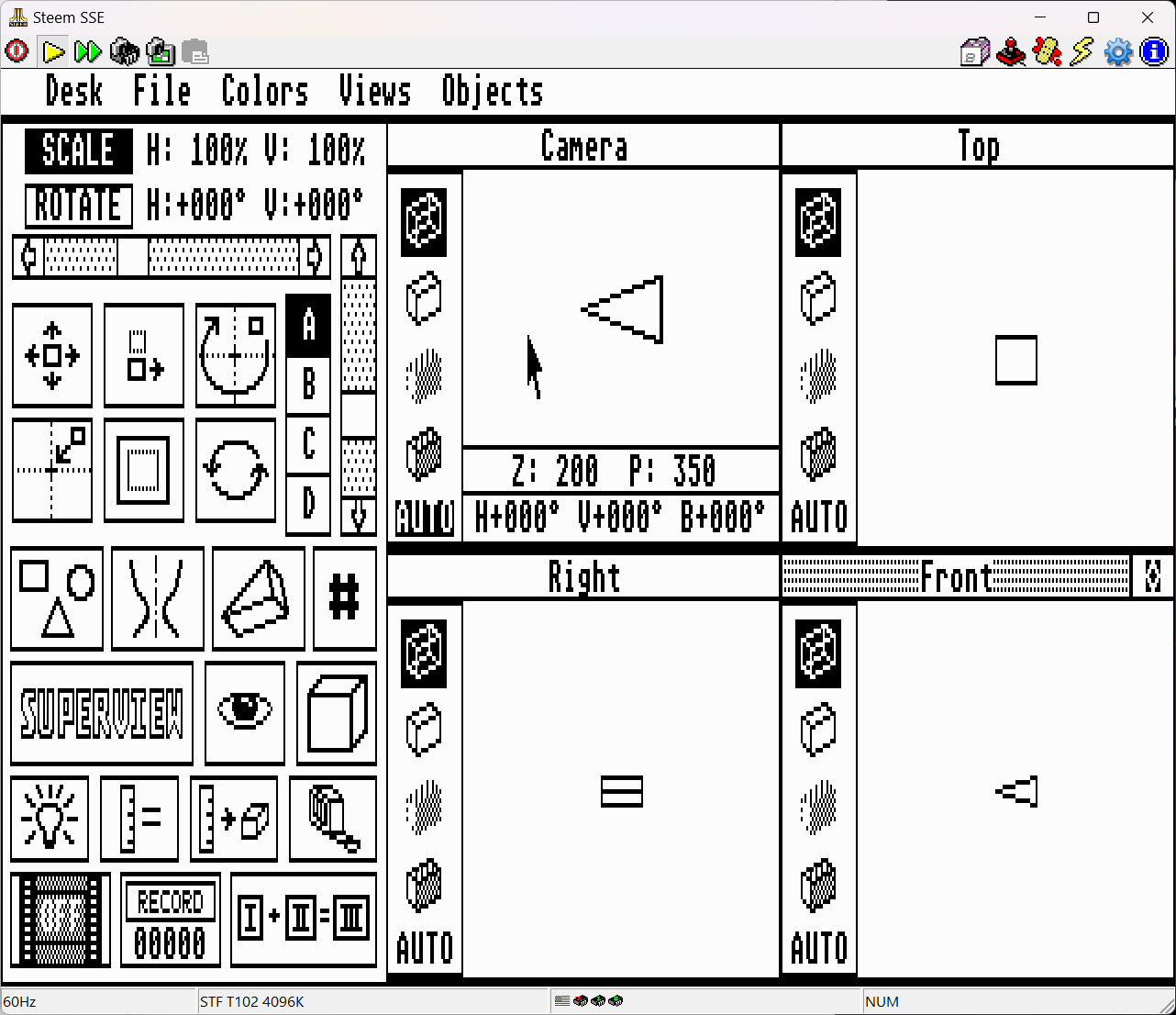

Once launched, I'm hit with a pretty intense set of tools and windows.

The left 1/3 of the screen is a fixed set of iconography for the tools. These were hidden away under menus in v1.0, but now they're front and left-of-center. The four-way split view on the right 2/3 of the screen is par for the modeling course.

What's different here is the Camera view is "look, but don't touch." I spent a lot of time trying to move things around in there before I remembered "RTFM". There was a moment early on with Electric Pencil when I felt attuned to its way of thinking, summoning menu commands without reading the manual. Deluxe Paint was the same, the tools doing intuitively what I expected. I really enjoy such moments when an affinity between the interface metaphor and my exploration is rewarded.

CAD-3D is resisting this, preferring to remain inscrutable for now.

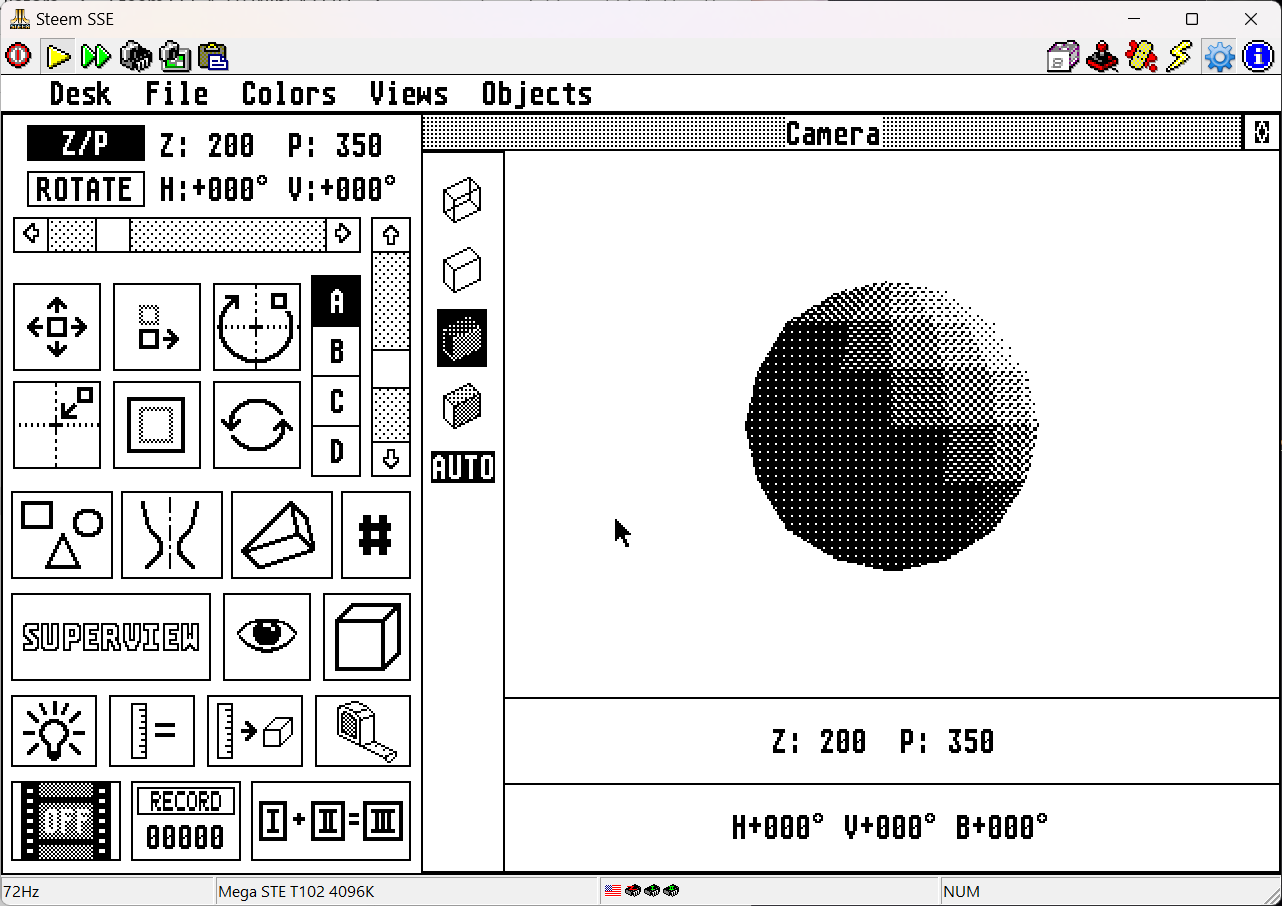

Screenshots in the manual contain a lot more fine detail than I see while using the program. In the GEM desktop preferences there was a greyed out "high resolution" option, unlocked by setting the emulator itself to a beefier 4MB MegaSTE. This hardware upgrade brings the display up to Macintosh-style high quality B&W, which feels very nice to use, but for this I want color so back to medium-res for me.

Feeling constrained

While the top/right/front views function similarly to modern modelers, these have one notable difference. They are not "cameras" into those views, they are showing you the full, literal totality of a cube which contains your entire 3D world.

Need more space? Make your objects very small. Objects are too small to see? Well, that's just how we do things here in 1986. It feels claustrophobic, but is also a simple mental model for comprehending "the universe" of your scene.

What I'm quickly learning is how the program is configured to conserve processing time and memory at all times. Changing a value, say camera zoom, doesn't change anything until you "apply" it. Shades of VisiCalc's "recalculate" function.

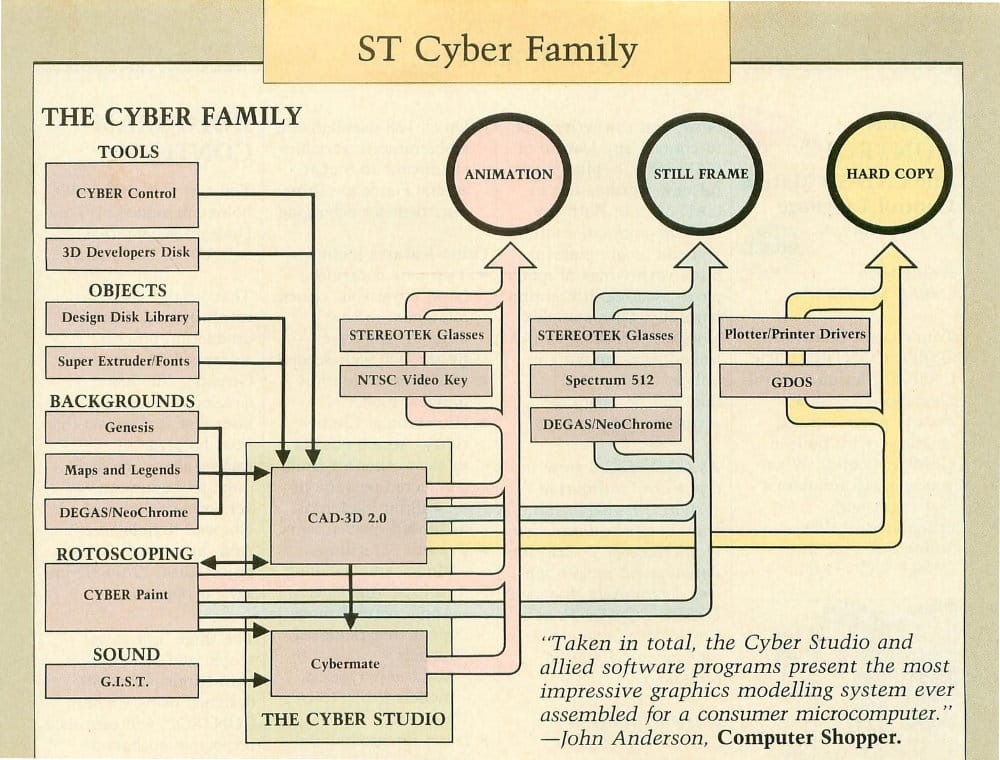

The low memory inherent to the hardware is subverted by a "split the advanced functions out into separate products" approach. Complex extrusions are relegated to Cyber Sculpt. Model texturing is available in Cyber Texture. Advanced compositing can be done in Cyber Paint.

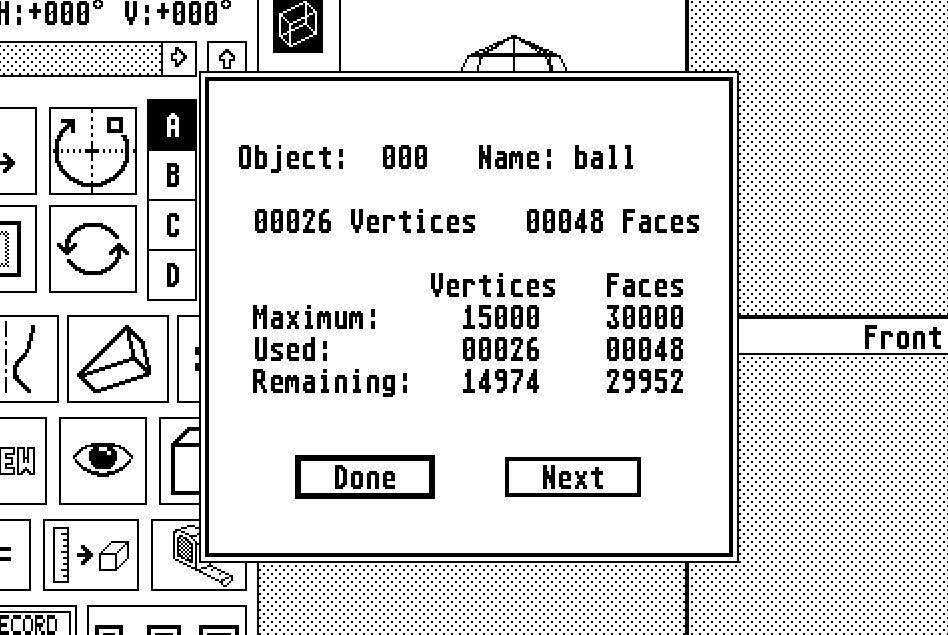

Memory budget is accessed by the big # button just left of the center of the screen. This will show how close you are to maximizing the vertex/face count of the scene. Again, shades of VisiCalc's free-memory counter ticking down to zero as you work.

Unnatural selection

Adjusting objects, by scale or position, requires selecting them. Despite the mouse and pointer GUI interface, there is no direct manipulation of objects to be found here. If you enjoy grabbing handles on objects and dragging them into scale and position, you're going to have some hard habits to break.

Object selection is convoluted; the basic tenet is "visible = selected."

The "Objects" modal window provides a button for every object. Each button toggles its associated object's visibility after you click "OK." Selections here will modify the currently active group, designated by the A B C D tools mid-screen.

Scaling sliders (left side of screen) affect every visible object along the active view's axes. So horizontal/vertical in "Top" view scales different axes than "Front" view. Per-object scaling is possible, but only if you deselect all but one object.

Switch from "Scale" to "Rotate" and the scaling sliders switch their function accordingly. Selections can be rotated around one of three pivot points: view center, selection center, or an arbitrary point within a given view. Sliders control horizontal and vertical rotation, but the third axis can also be rotated upon, though for some reason it was decided this should be via a pop-up window pie chart.

CAD-3D renders in the ST's 16-color low resolution mode. Applying a color to an object is setting the "brightest" color for rendering that object. Any other colors within that color's (user-definable) group will fill in the mid and darker tones. Simple palette gradients make for "realistic" lighting, but bright orange highlights with fluorescent green shading is also possible, if you want to fight the power.

Addition and subtraction

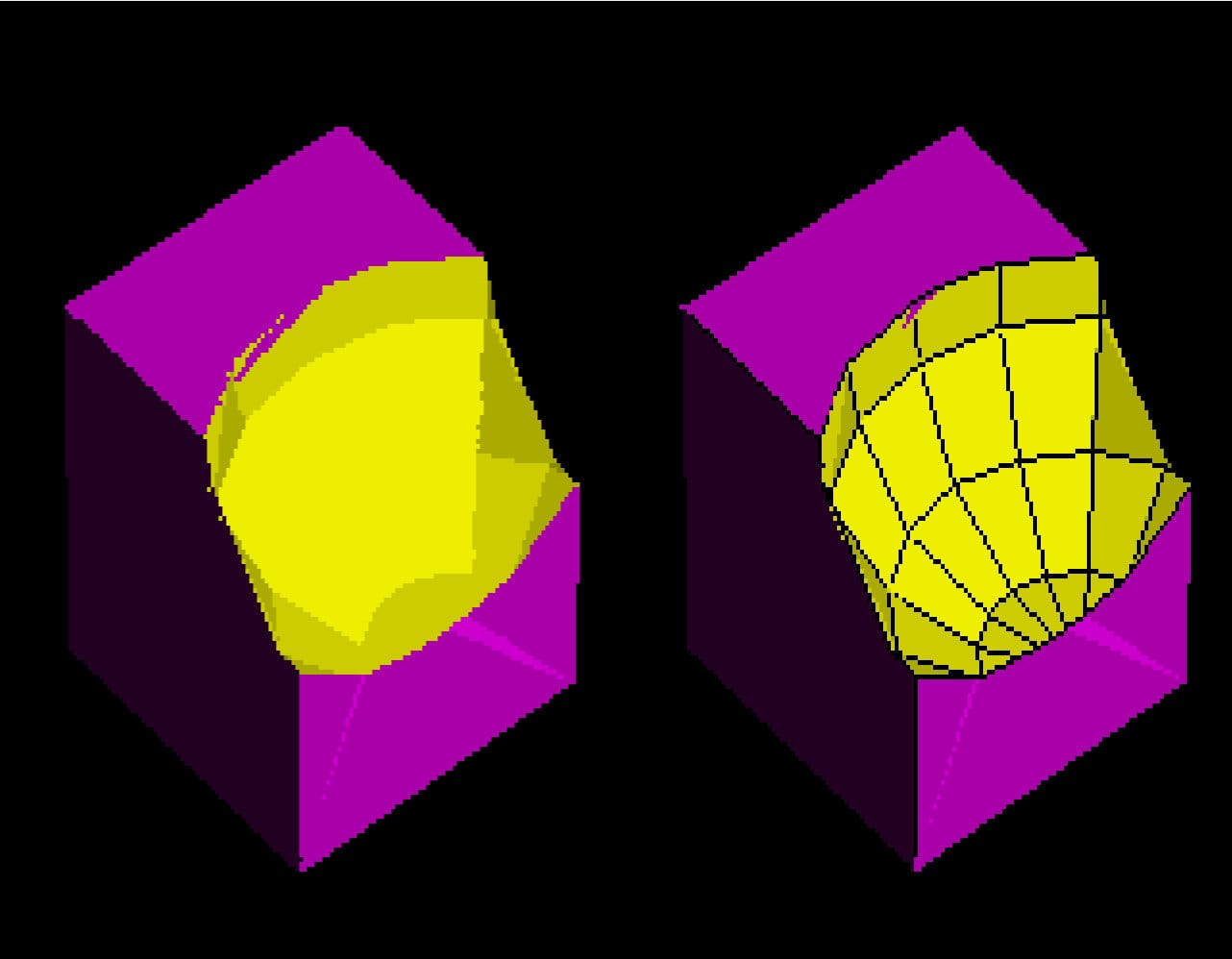

In the toolbox, at the bottom, is an unassuming button labelled I + II = III. This is a boolean tool, presented as a kind of equation builder called "Object Join Control." Choose an action: Add, Subtract, And, or Stamp. Select the first object then the second object, and name the resulting object. "Add" will produce something like object1 + object2 = object3. "Subtract" will read object1 - object2 = object3 and so on.

With this tool we have what we need to sculpt complex, asymmetric figures. To paraphrase Michelangelo, the shape we want is already inside the primitive volume. We just have to remove the superfluous parts and set it free. If only I were so talented.

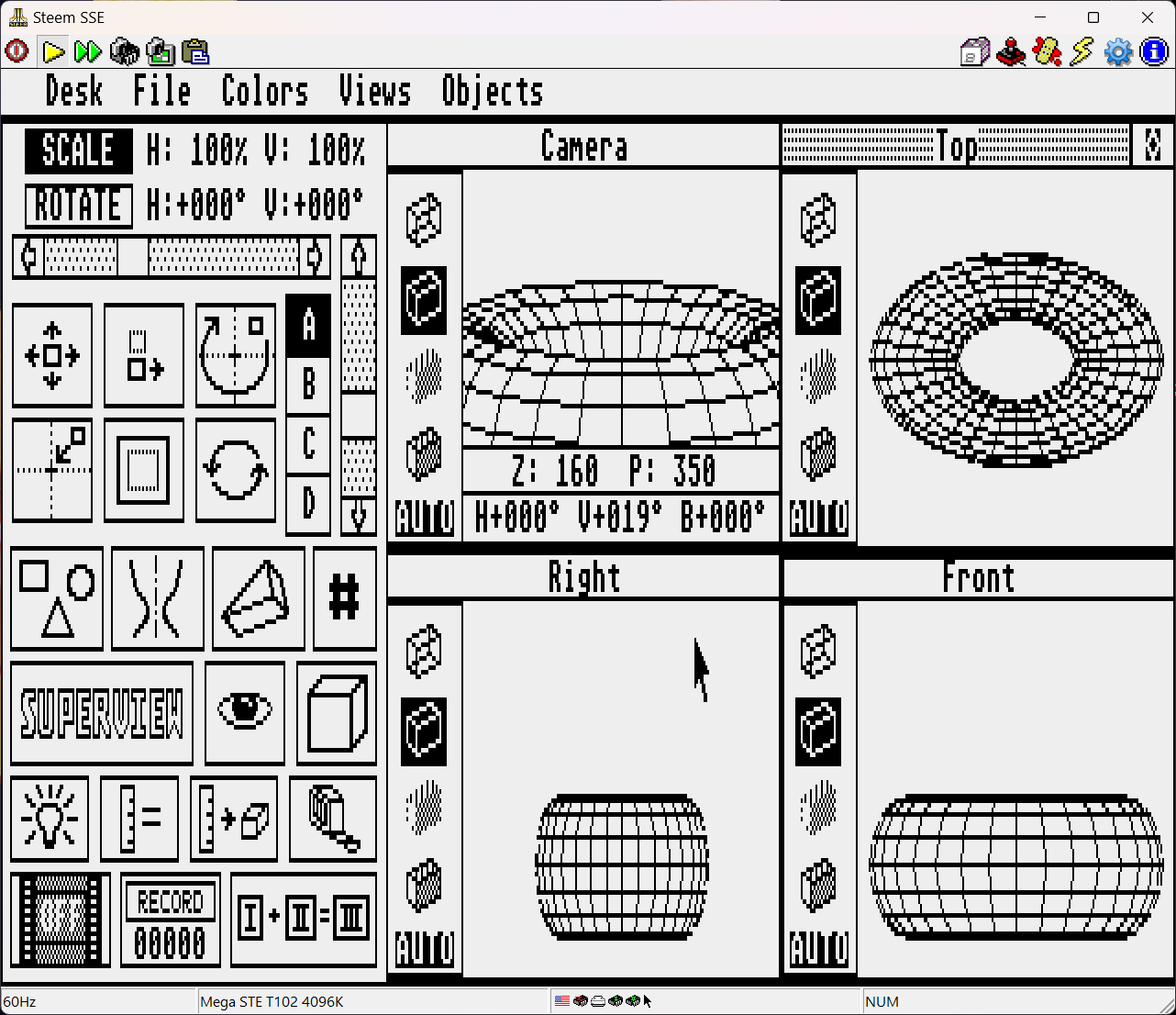

Like sculptors of yore, setting shapes free can take a lot of time. Click "OK" on a join operation and prepare to wait, depending on the number of faces involved. I put down a default sphere "3" and a default torus, shrank the torus a bit to intersect with the sphere's circumference, and requested sphere - torus.

Now I've done it.

Even at top emulator speed in overdrive I've been waiting well over 20 minutes for the subtraction to complete. Did I kill it? Is this like in The Prisoner when #6 made the computer self-destruct?

Despite the computation time, there are very good reasons for performing booleans beyond the sculpting power they impart. Earlier I noted that there is a vertex/face count limit on the scene. Intersecting objects added together can reduce their vertex count by eliminating interior and unused faces.

It also turns out there is a 40 object limit to our scenes. Adding two objects together reduces them to one, deleting the originals. Understand that there is no undo function. Only a rigorous discipline of saving before performing such destructive functions will save you from yourself if you needed the original objects. This will become the mantra for this blog, "Save often, kids."

Boolean functions respect object colors, which makes for neat effects. Subtract a yellow sphere from a purple cube and the scoop taken out of the cube will be yellow while the rest of the cube stays purple. A pleasant surprise!

The "Stamp" option tattoos the target surface with the shape and color of the second object. Stencil text onto surfaces (provided you have 3D text objects), add decorative filigree, generate multi-color objects, and so on. It kind of depends on how well you can master the stiff, limited extrude tools to generate surfaces worth stamping.

OK, this torus/sphere boolean operation still isn't done, so I'm chalking it up as, "This is a thing CAD-3D cannot do." While waiting for the numbers to crunch, I realized I could create the intended shape manually with a custom lathe. Only while experiencing the computational friction did the second method occur to me. That reminds me of something I've been thinking about since starting this site.

What we lose when we lose friction

Working with retro-computing means choosing to accept the boundaries of a given machine or piece of software. Working within these boundaries takes real, conscious effort; nothing comes easy. Meanwhile, technology in 2025 is designed to make the journey from "I want something" to "I have something" instantaneous and frictionless.

It is a monkey's paw fulfilling wishes, and like a monkey's paw, it can go wrong. Not just "turkey's a little dry" wrong, but "it obscures objective truths" wrong.

The first is seen with (say it with me now) the spread of AI into everything. You want something? Prompt and get it. Our every whim or half-considered idea must be rewarded, nay PRAISED! We needn't even prompt, services will prompt on our behalf. Every search delivers what you asked for, even if it delivers lies to do so.

There are plenty of others more qualified to discuss the ramifications of AI on the arts, society, and our very minds. For this article I want to use it to illustrate what much of tech has become: an unchallenging baby's toy. A pacifier.

Another way "friction" is stigmatized as detrimental is, admittedly, a personal bias but I know I'm not alone. UI density is typically considered "friction" and it's "bad" because a user may disengage from a piece of software. To keep engagement up, interfaces simplify, slowly conflating "user-friendly" with "childlike."

The net result is a trend toward UIs with scant few pieces of real information distributed over vast plains of pure white or oversaturated swoops of color. UI/UX professionals like to call it "playful" or "delightful."

I don't want to come off as a killjoy against "fun" user interfaces, but I'm an adult. I eat vegetables as well as candy. Where are the vegetables in the modern tech landscape? Where is the roughage which requires me to chew on its ideas?

The industry wants to eliminate friction, but without friction there can be no spark.

"Spark" is what I felt struggling against a hyper-strict budget during my publishing days. I found it when examining the depth of Deluxe Paint in the animation controls. It is what I felt when I overcame the Y2K bug in Superbase. I felt it again just now as I realized the lathe solution while waiting for the boolean to finish. Each little struggle forced me to shift my frame of mind, which revealed new opportunities.

If my very first thought is brought to life instantly, with no artistic struggle (one hour of prompting is not a struggle), then why ever "waste time" thinking of second options? Or alternate directions? Even, heaven forbid, throwing ideas away? These common creative pathways are discouraged in a modern computing landscape.

Put another way, I can't think of a time when my first idea was my best idea.

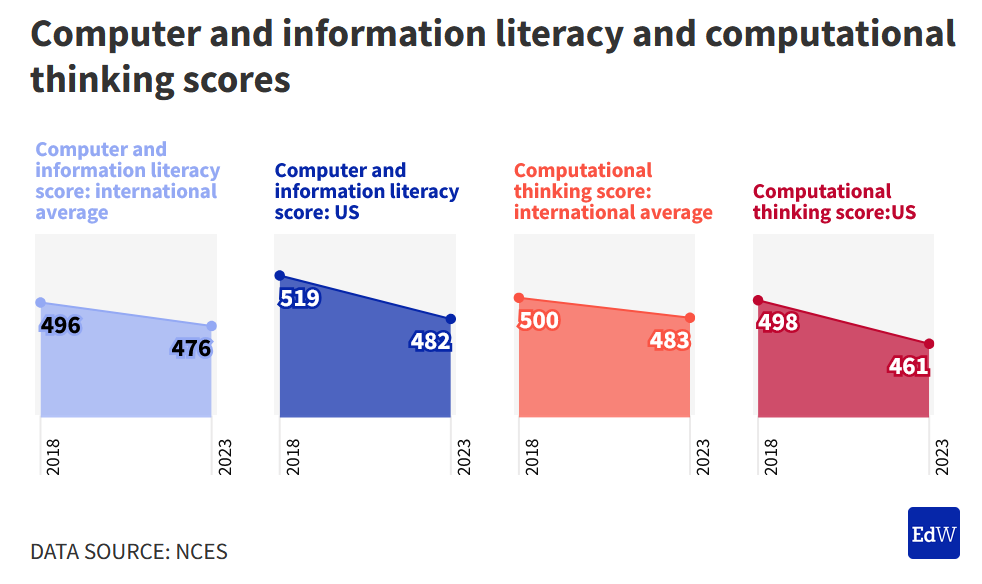

Given the protective bubble-wrap our software tends to wrap itself in, perhaps it will not surprise you that computer literacy and computational thinking scores have dropped in the US over the past five years.

Hypocrite much?

Some readers may be thinking, "In the Deluxe Paint article you picked on Adobe for airplane cockpit UIs. Isn't that the "friction" you're describing?" That is complexity, which can cause a type of friction, true. But it is the friction of a rug-burn, not a spark.

Object permanence

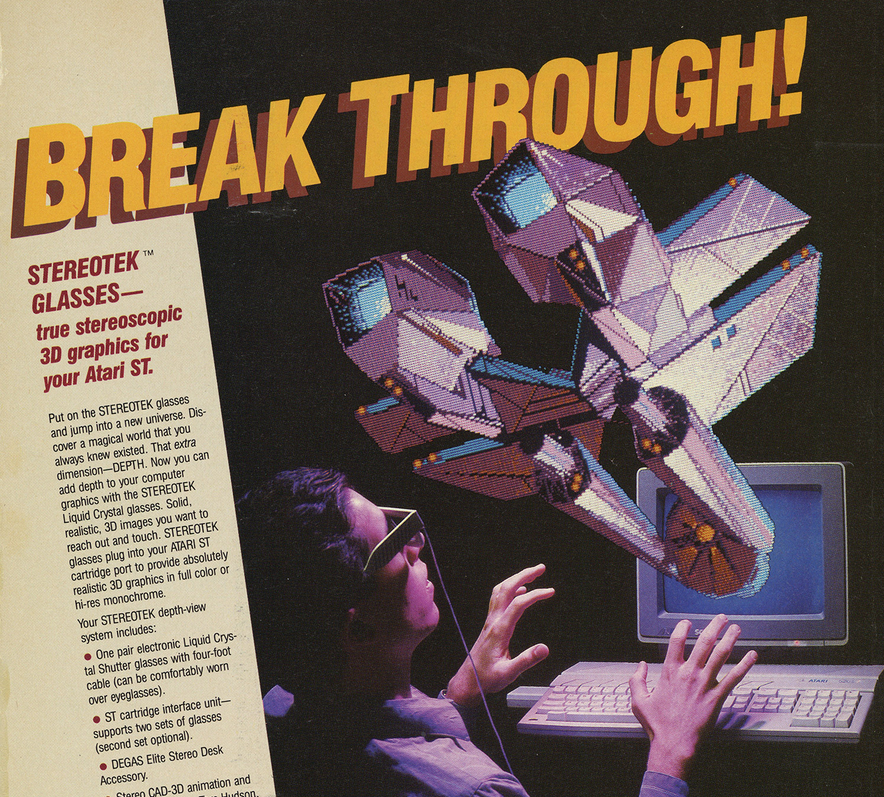

Back into the program, I've only touched on it so far, but that "Superview" button is far more important than its obfuscated name suggests. That is the renderer. Double-click it for options, like rendering style and quality, including stereoscopic if you're lucky enough to own the Stereotek 3D glasses.

Images, for example previous renders, can be brought in as a background for a new render. All drawing is restricted to the same 16-color palette though, so plan accordingly.

The basic wireframe renderer is quite interesting because it provides real-time interactive view manipulation, like a video game. That makes sense because the algorithm that drives this view came from a video game. It was purchased by Hudson from Jez San, the creator of real-time 3D graphics game Starglider. Even if you never touched Starglider, you know San's work today. He was a developer of the Super FX chip for Nintendo, which made Starfox on the SNES possible.

Animated expression

CAD-3D has one more significant trick up its sleeve. Using a simple, clever method of XOR compression, animations can be generated.

Turn "ON" animation with the clapboard icon. Set up the scene and camera position for a frame. Capture a render with "Superview." Commit that frame to the sequence with the frame counter icon. Repeat until you're done. It's stop-motion animation, essentially.

This is time consuming and requires some blind trust as there is no previewing your work. Luckily, a more elegant, and far more complex, option comes bundled on disk in the form of an entire movie-making scripting language. I tried to understand it, but my utter lack of ability to make movies was exposed.

I wanted to at least try the on-disk animation tutorial. Unfortunately, the program which can play back the XOR compression method is nowhere to be found. No disk image I could find contained it.

Regardless, the scope of what was being attempted with this product, and really the entire suite, is clear. ANTIC Software wanted your Atari ST to be nothing short of a full movie-production studio. If there were some way to calculate price per unit of coolness, an ST paired with CAD-3D may be quite high up that chart.

Time to ditch Blender?

Put simply, no. On its own CAD-3D lacks modeling and rendering tools which many would consider absolute basics in a modern workflow. Lighting control is restrictive, there are no cast shadows, no dithering to make up for the limited rendering palette, extrusion along splines isn't possible, views into the world are rigid and hard to work in, and basic object selection requires a clunky series of menus and button presses. A theoretical v3.0 could have been amazing.

But I must concede a few points here.

First, this is really just one part of a larger package. It's the main part, but not the only part. The bundled scripting was expanded into Cyber Control and the bundled "super extruder" was expanded into Cyber Sculpt, for example. There was a VCR controller, genlock support, stereoscopic 3D glasses support, multiple paint programs, a sound controller, and more. Certain deficiencies are more than adequately compensated for if we take the full suite into account.

Second, there's something to be said about the simple aesthetic of CAD-3D. There is absolutely a subset of people out there who just want to play with 3D like a toy, not a career. I think the success of PicoCAD speaks to this; just look at the fun things people are creating in a 128x128, 16-color modeler in 2025.

Third, working within limits is, paradoxically (and also well-acknowledged), creatively freeing. The human need to bend our tools beyond their design is a powerful force. We see it when a working Atari 2600 is built within Minecraft. We see it in the PicoCAD projects I linked to above. Full-screen, full-motion video on a TRS-80 Model III? Hey, why not?

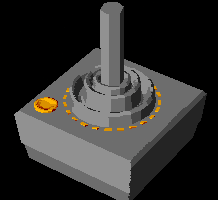

In that sense, I can feel a pull toward CAD-3D. I managed to model a none-too-shabby CX40 joystick, and I catch myself wondering now what more I could do. I started feeling a groove with its tools, so how far could I push it? How far could I push myself?

I hope you'll understand my positive take on CAD-3D when I say, there is friction to be found here.

Sharpening the Stone

Ways to improve the experience, notable deficiencies, workarounds, and notes about incorporating the software into modern workflows (if possible).

Emulator Improvements

As you may expect, enable the best version of the system you can. TOS 4.x seems to be incompatible with CAD-3D, so keep the OS side simple. In fact, it's better to crank up the virtual CPU speed than to fumble around with toggling on/off the warp mode. It's less fiddly and doesn't suffer from key repeat troubles.

Troubleshooting

- Neither the application nor OS ever crashed on me even once. There's a lot to be said for that stability.

Getting Your Data into the Real World

- Converting the 3D data into a format that could be brought into Blender, for example, seems like a bespoke conversion tool would be needed. I've not found such a thing yet.

- .PI1 render files can be converted into .pngs thanks to XnConvert.

- I don't know of a way to convert animations, though a capture system like OBS Studio would work in a pinch. You could also render each frame out separately and stack them together into a movie file. ImageMagick's

animatefunction can take a folder of sequentially numbered images and stitch them together into a movie.

What's Lacking?

- Rendering quality. The engine can't do dithering, and the flat colors of the limited palette can visually flatten a render that isn't very carefully lit.

- Getting around object limitations means locking yourself out of scene design flexibility as you "Add" multiple objects together to collapse them into single objects and reduce the object count.

- The object selection process really hurts.

Fossil Record