HyperCard on the Macintosh

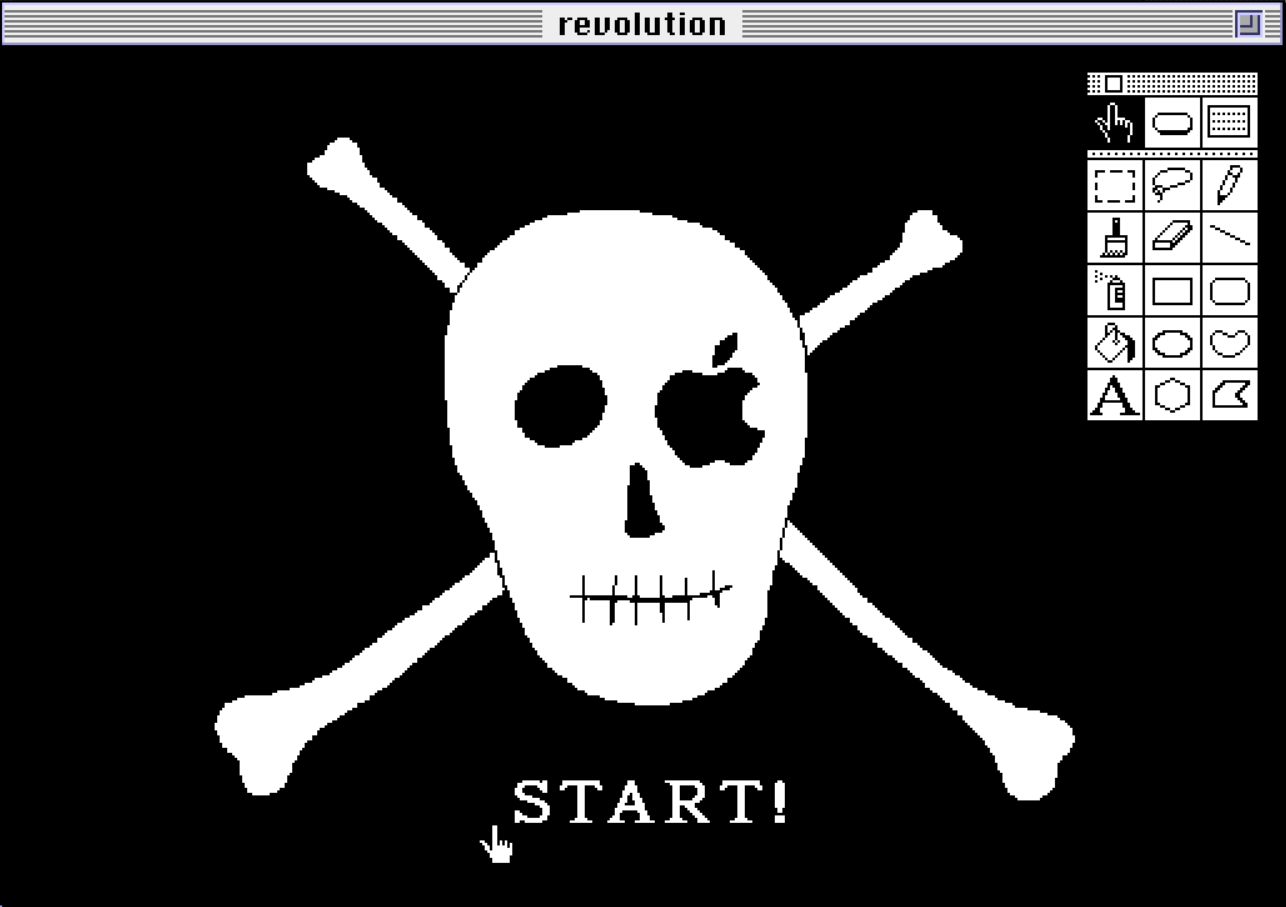

There was once a tool so perfectly executed that careers, conventions, magazines, and entire companies were born from its vision and aesthetic.

Throughout the Computer Chronicles's 19 years on-air, various operating systems had full episodes devoted to them, like Macintosh System 7, UNIX, and Windows 95. Only one piece of consumer software had an entire episode devoted to it. You can see and hear Stewart Chiefet's genuine excitement watching Bill Atkinson show it off.

Later, Chiefet did a second full episode on it. HyperCard was a "big deal."

Big, new things are scary. In a scathing, paranoid, accidentally prescient article for Compute Magazine's April 1988 issue, author Sheldon Leemon wrote of HyperCard, "But if this (hypertext) trend continues, we may soon see things like interactive household appliances. Imagine a toaster that selects bread darkness based on your mood or how well you slept the night before. We should all remember that HyperCard and hypertext both start with the word hype. And when it comes to hype, my advice is 'just say no.'"

Well, you can't make Leemonade without squeezing a few Leemons, and this Leemon was duly squeezed.

"Do we really want to give hypertext to young school children, who already have plenty of distractions? We really don't want him to click on the section where the Chinese invent gunpowder and end up in a chemistry lesson on how to create fireworks in the basement." (obligatory ironic link)

Leemon-heads were in the minority, obviously. Steve Wozniak called Atkinson's brainchild "the best program ever written." So did David Dunham. There was a whole magazine devoted to it. Douglas Adams said, "(HyperCard) has completely transformed my working life." The impact it made on the world is felt even today.

Cyan started life as a HyperCard stack developer and continues to make games.

Wikipedia was born from early experiments in HyperCard.

The early web was strongly influenced by HyperCard's (HyperTalk) vision.

Cory Doctorow's first programming job was in HyperCard.

Bret Victor built "HyperCard in the World," which evolved into Dynamicland.

With a pedigree like the above, it is no spoiler to say that HyperCard is good. But I must remove the spectacles of nostalgia and evaluate it fairly. A lot has happened since its rise and fall, both technologically and culturally. Can HyperCard still deliver in a vibe-coded TypeScript world?

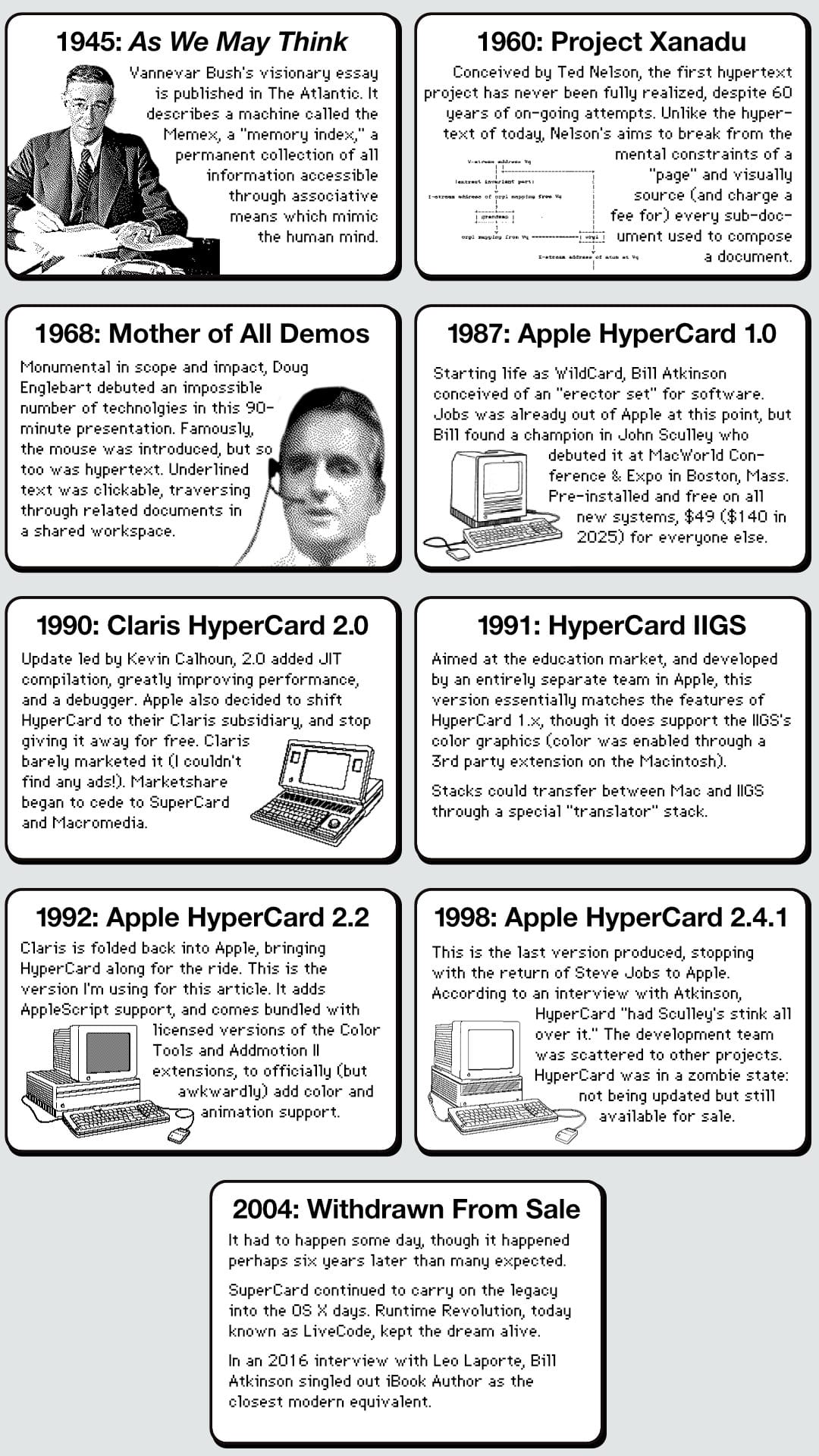

Historical Record

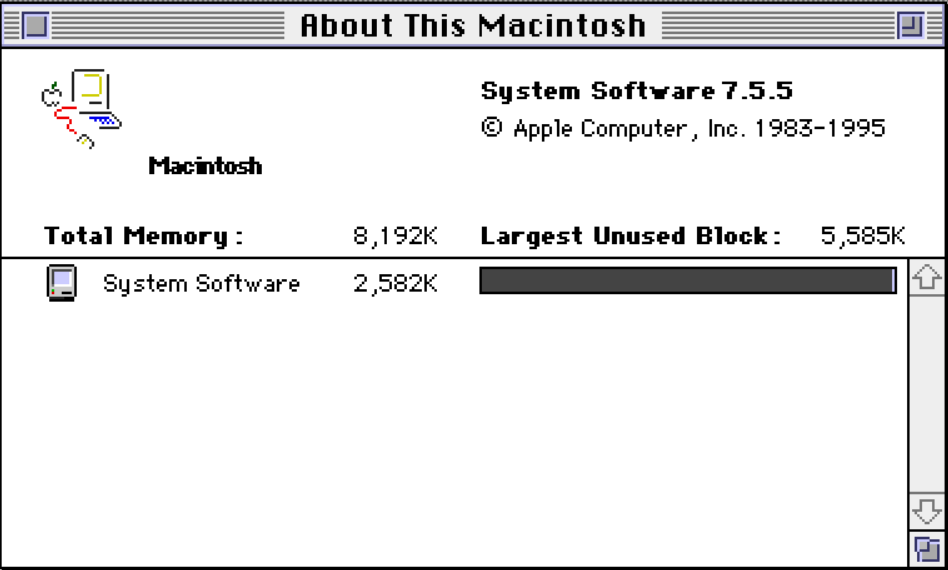

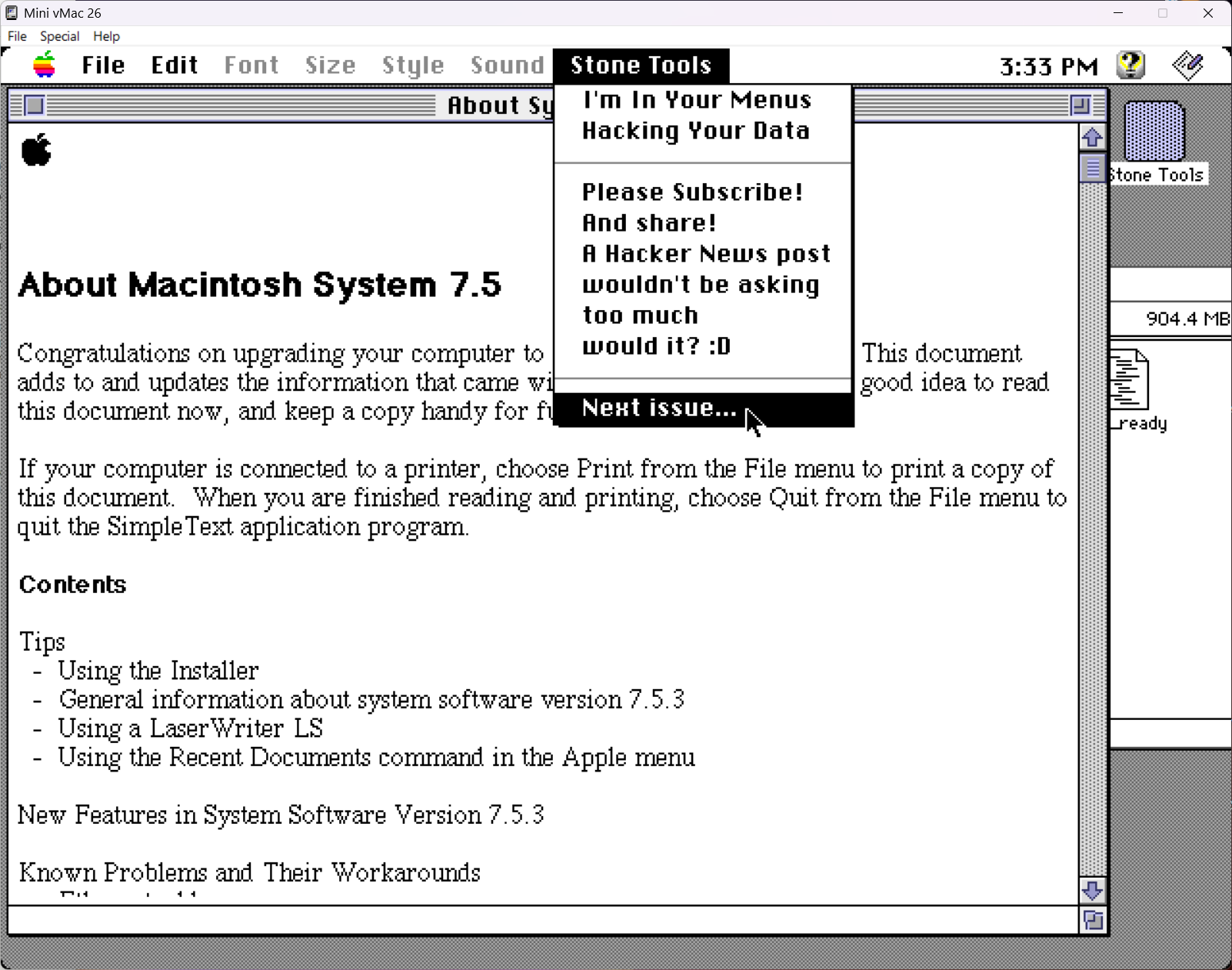

Testing Rig

- Mini vMac v36.04 for x64 on Windows 11

- Running at 4x speed

- Magnification at 2x

- Macintosh System 7.5.5 (last version Mini vMac supports)

- Adobe Type Manager v3.8.1

- StickyClick v1.2

- AppleScript additions

- 8MB virtual RAM (Mini vMac default)

- HyperCard 2.2 w/scripting additions

Version 2.2 of HyperCard is significant for a few notable reasons: first, it adds AppleScript support, then it adds a script debugger, and finally it marks the return of HyperCard from Claris back into Apple's fold.

Let's Get to Work

Reviewing and evaluating HyperCard is a bit like trying to review and evaluate "The Internet." And MacPaint. And a full application development suite. A sane man would skedaddle upon seeing the 1,000 (!) pages of The Complete HyperCard 2.0 Handbook, 3rd Edition by Danny Goodman, but not this man. Make of that what you will.

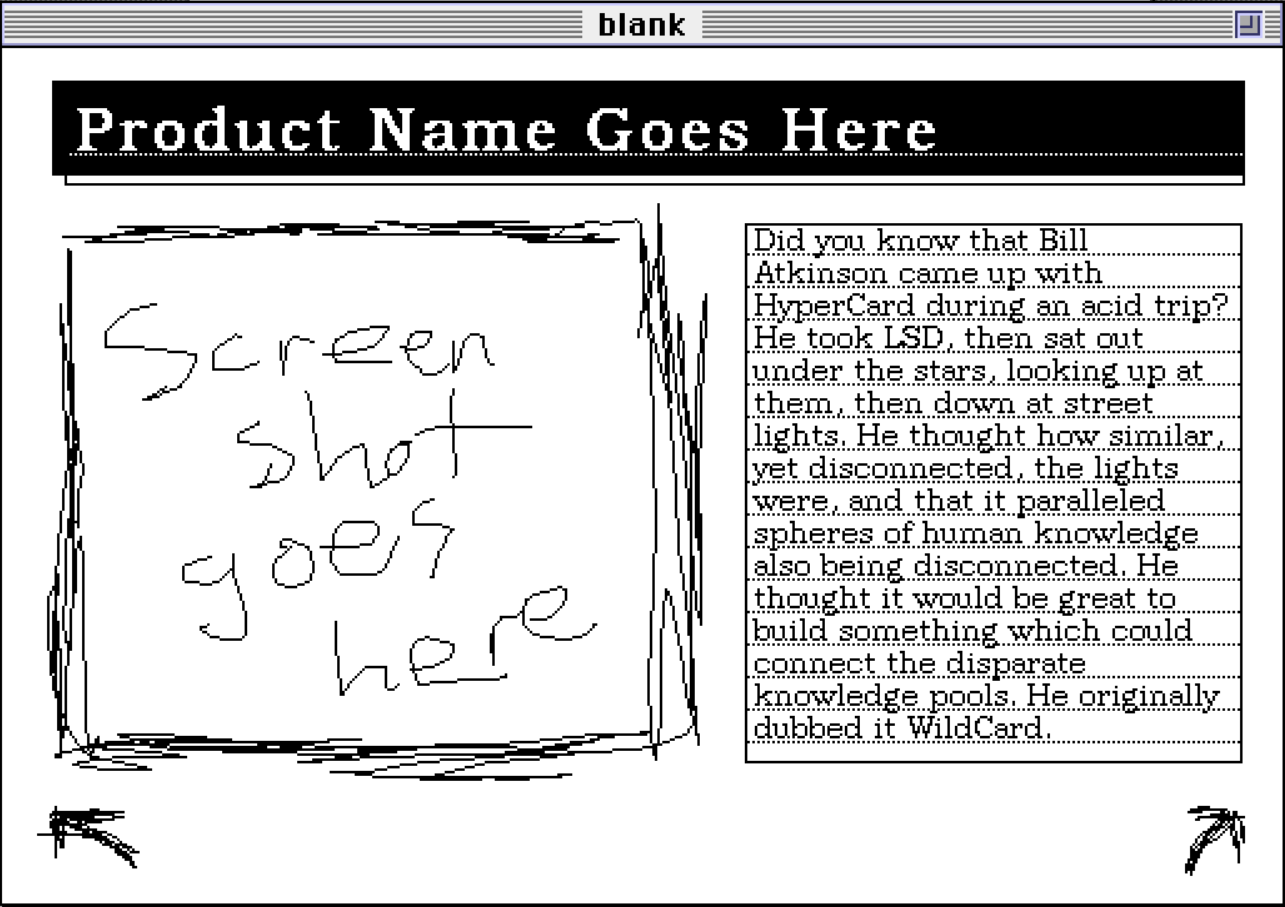

It's difficult to choose a specific task for this post. I'll build the sample project from the Handbook, but let's note what the book says about its own project, "In a sense, the exercise we’ll be going through in this chapter is artificial, because it implies not only that we had a very clear vision of what the final stack would look like, but that we pursued that vision unswervingly. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth."

I have no such clear vision. It's kind of like staring a blank sheet of paper and asking myself, "What should I make?" I could fold it into origami, use it as the canvas for a watercolor painting, or stick it into a Coleco ADAM SmartWriter and type a poem onto it. Art needs boundaries, and I don't yet know HyperCard's.

So, I'll just start at the beginning, launch it, and see where it takes me.

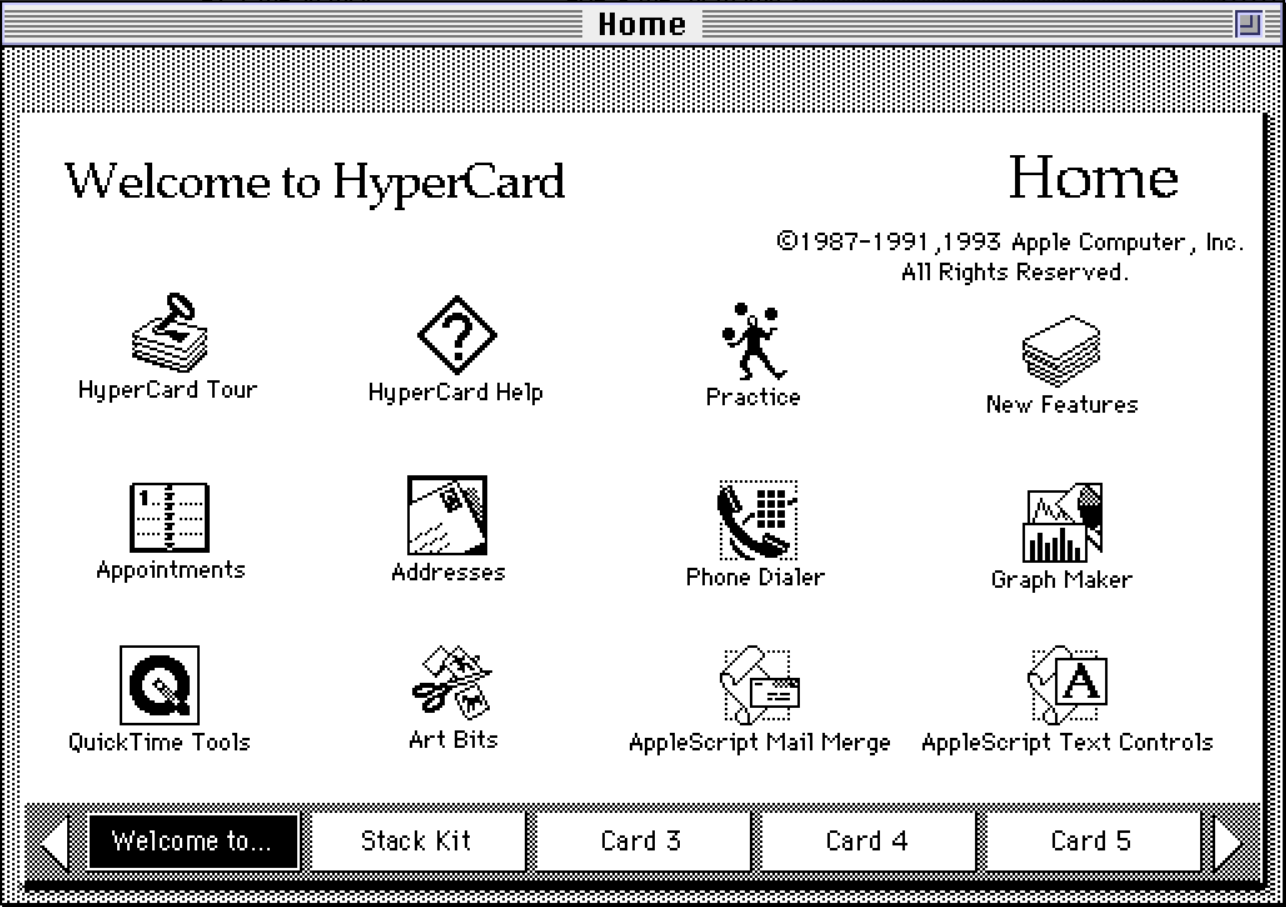

Launching HyperCard takes me to the Home "stack," where a "stack" is a group of related "cards" and a card is data supercharged with interaction. In beginner's terms, it's fair to think of a stack as an application, though it requires HyperCard to run. (HyperCard can build stand-alone apps, but that's not a first-time user's experience).

Atkinson does mean to evoke the literal image of a stack of 3x5 index cards, each holding information and linked by relationships you define. Buttons provide the means to act on a card, stepping through them in order, finding related cards by keyword, searching card data, or triggering animations. All of this is possible, trivially so.

At first blush that doesn't sound particularly interesting, but MYST was built in it, should you have any doubt it punches above its weight class.

Today, I can describe a stack as being "like a web site" and each card as being "like a page of that site," an intellectual shorthand which didn't exist during HyperCard's heyday. To use another modern shorthand, "Home" is analogous to a smartphone's Home screen, almost suspiciously so. You can even customize it by adding or deleting stacks of personal interest to make it your own.

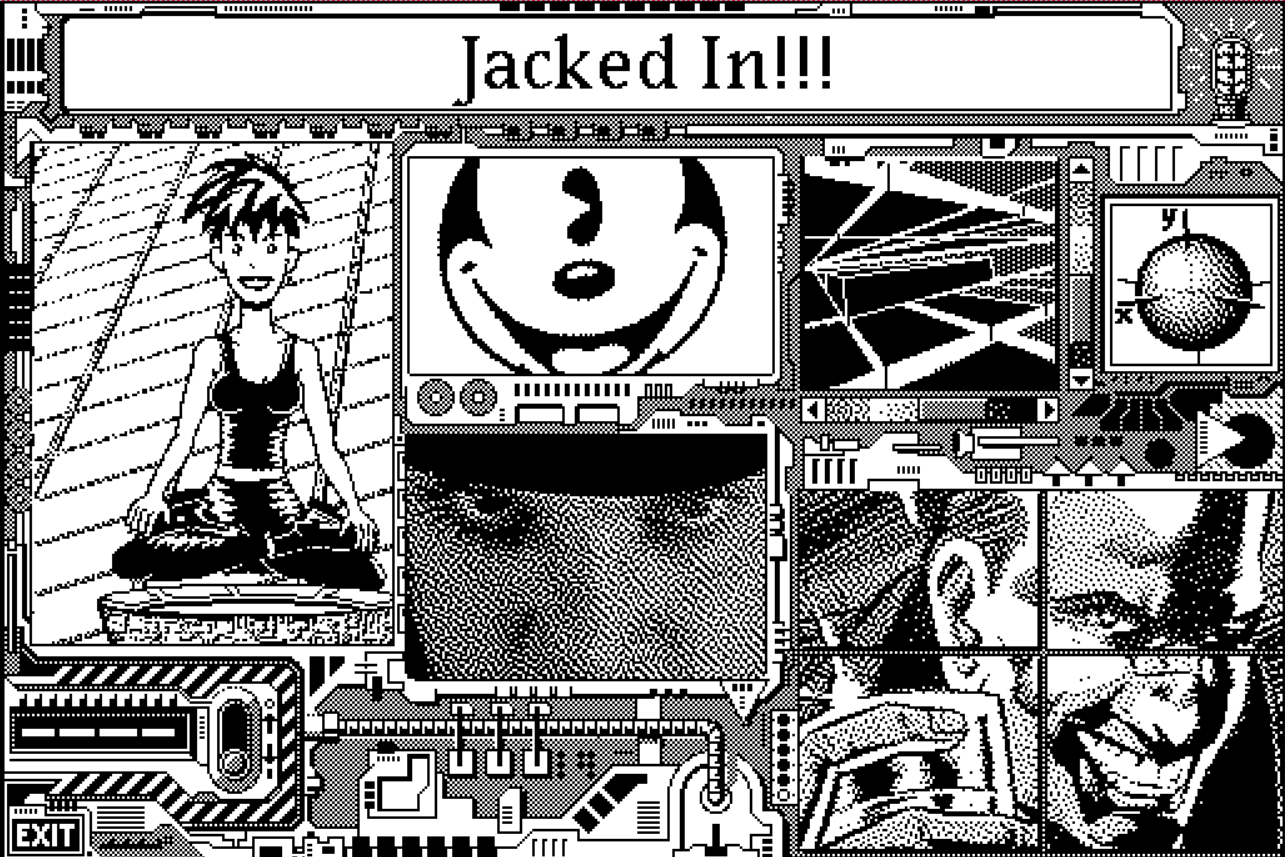

(contains intense flashing strobe effects) Beyond Cyberpunk pushed HyperCard boundaries in its own way. A web version is available, minus most of the original charm.

Let this serve as an example

Walking through the Home card, the included stacks provide concrete examples illustrating the power of HyperCard's development tools. Two notable features are present, though they are introduced so subtly it would be easy to overlook them.

The first is the database functionality the program gives you for free. Open the Appointments or Addresses stacks, enter some information, and it will be available on next launch as searchable data. It's stored as a flat-file, nothing fancy, and it's easier than Superbase, which was already pretty easy.

The second is that after entering new data into a stack, you don't have to save; HyperCard saves automatically. It's happens so transparently it almost tricks you into thinking all apps behave this way, but no, Atkinson specifically hated the concept of saving. He thought that if you type data into your computer and yank the power plug, your data should be as close to perfect as possible.

This "your data is safe" behavior is inherent to every stack you use or build. You don't have to opt-in. You don't have to set a flag. You don't have to initialize a container. You don't need to spin up a database server. You don't even have to worry about how to transfer the data to another system; the data is all stored within the data resource of the stack itself. Just copy the stack to another computer and be assured your data comes with you.

There is one downside to this behavior as a typical Macintosh end-user. If you want to tinker around with a stack, take it apart, and see how its built, you must make sure you are working with a copy of that stack! As saving happens automatically, it can be easy to forget that your changes are permanent, "I didn't hit save! What happened to my stack?"

Thus, an original stack risks getting junked up or even irreparably broken due to your experiments. "Save your changes" behavior is taught to us by every other Macintosh program, but HyperCard bucked the careful conditioning Mac users had learned over the years.

Consumption tax

At its most basic level, without even wanting to make one's own stacks, HyperCard offers quite a lot. Built-in stacks give the user an address book, a phone directory, an appointment calendar, a simple graph maker, and the ability to run (and inspect!) the thousands of stacks created by others.

The bundled stacks are easy to use, but far from being "robust" utilities. That said, they're prettier and easier to user than a lot of the type-in programs from the previous 8-bit era and you're free to modify them to suit your needs, even just aesthetically. Free stacks were available on BBS systems, bundled with books, or on cover disks for magazines.

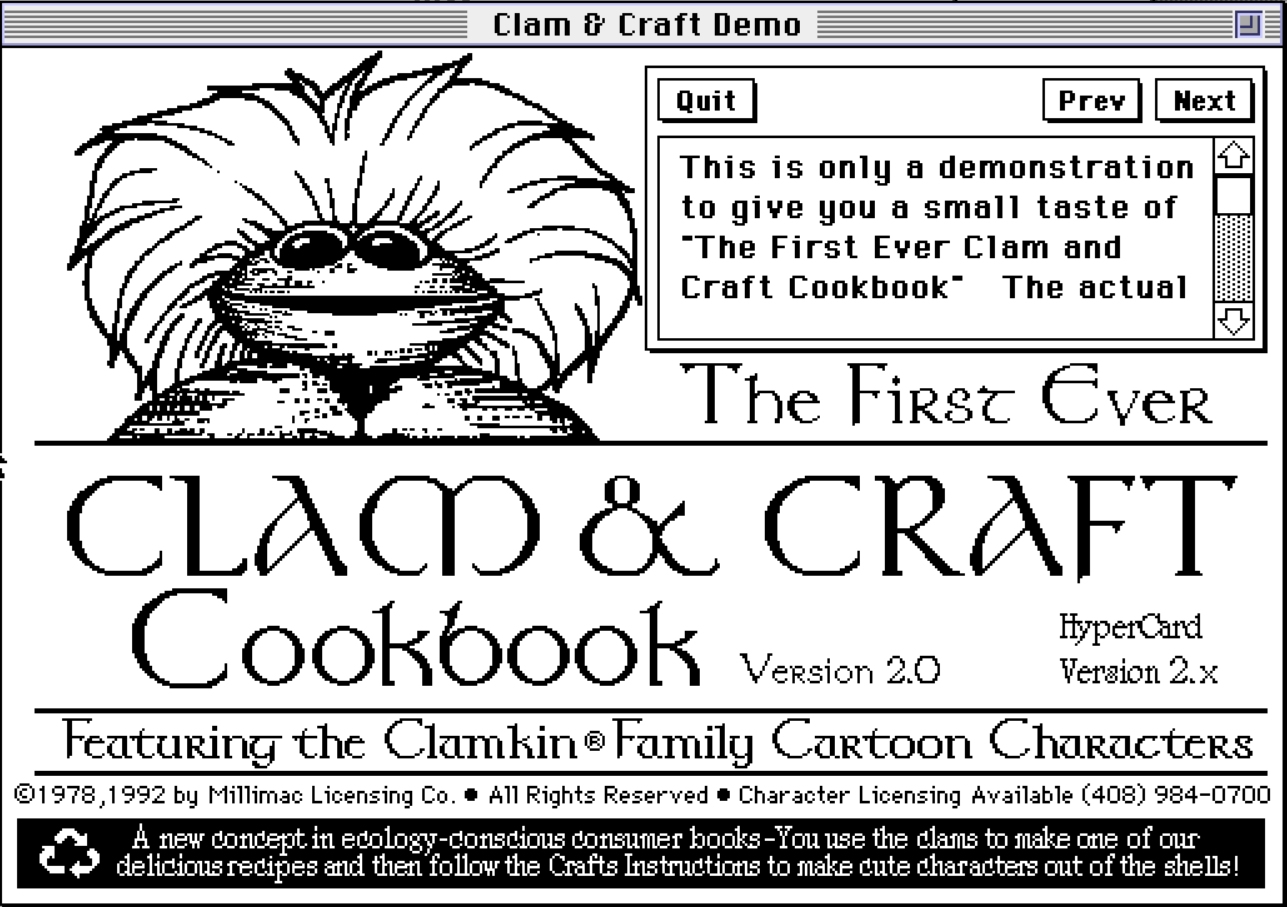

HyperCard offered a first glimpse at something slantingly adjacent to the early world wide web. Archive.org has thousands of stacks you can look through to get a sense of the breadth of the community. Learn about naturalism, read Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (official release!), or practice your German. There are TWO different stacks devoted to killing the purple children's dinosaur, Barney. Zines, expanded versions of the bundled stacks, games, and other esoterica was available to anyone interested in learning more about clams and clam shell art. I am being quite sincere when I say, "What's not to love?"

Card shark

Content consumption is fine and dandy, but it is on content creation which HyperCard focuses the bulk of its energies. With so many stacks expressing so many ideas, and reading how many of those were made by average people with no programming experience, the urge to join that community is overwhelming.

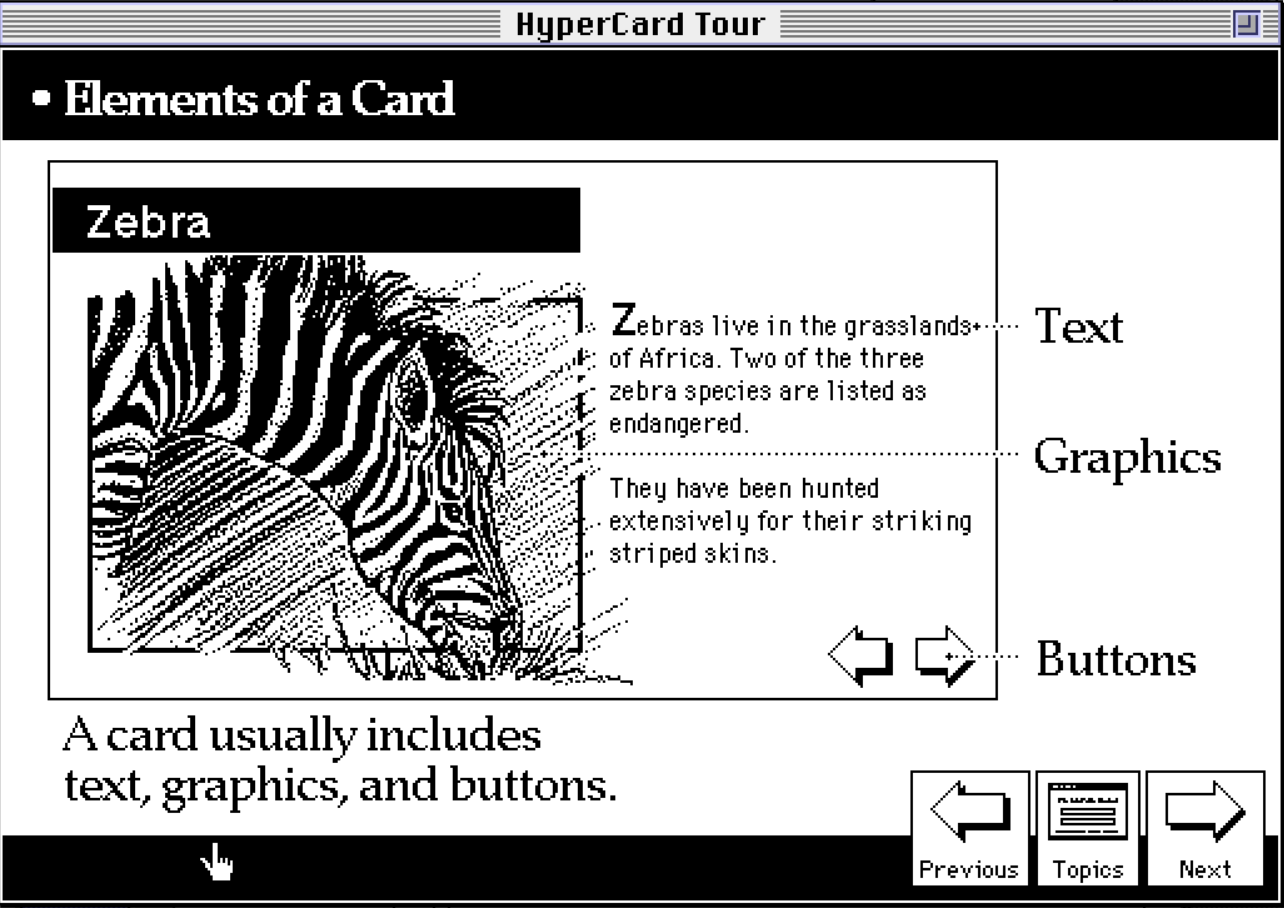

Cards are split into two conceptual domains: the background and the foreground. In modern presentation software like PowerPoint or Google Slides, these are equivalent to the template theme (the stuff that tends to remain static) and the slide proper (the per-slide dynamic attributes).

The layers of each domain start with a graphic layer fixed to the "back." Every object added to the domain, like a button, is placed on its own numbered layer above that graphic layer, and those can be reordered.

It's simple enough to get one's mind around, but the tools don't do a particularly good job of helping the user visualize the current order of a card's elements. Each element must be individually inspected to learn where it lives relative to other layers (objects). An "Inspector" panel would be lovely.

Designs on greatness

HyperCard has basic and advanced tools for creating the three primary elements which compose a card: text, graphics, and buttons. These elements can exist on both background and/or foreground layers as you wish, keeping in mind that foreground elements get first dibs on reacting to user actions.

Text appeal

Text is put down as a "field" which can be formatted, typed into, edited, copy/pasted to & from, and made available to be searched. That grants instant database superpowers to the stack. Usually a field holds an amount of text which fits visually on the card, but it can also be presented as a scrollable sub-window to hold a much larger block of text for when your ideas are just too dang big for the fixed card size.

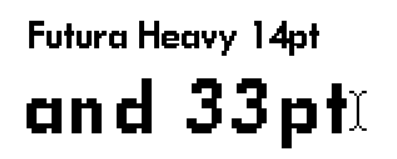

Control over text formatting is more robust than expected. Kerning is non-existent, but font, size, character styles, alignment, and line spacing are available. Macintosh bitmap fonts shipped in pre-built sizes, meaning they were hand-drawn expressly to look their best at those sizes. Scaling text is allowed, but you may need to swallow your aesthetic pride. Or draw the text yourself?

Quick on the draw

"Draw the text yourself" is a real option, thanks to the inclusion of what seems to be a complete implementation of MacPaint 1.x. The tools you know and love are all here, with selectable brush width, paint/fill patterns, lasso tool, shapes both filled and open, spray can, and bitmap fonts (if you don't need that text to be searchable). Yes, even the fabled eraser which drew such admiration during Atkinson's first MacPaint public demo is yours. Yesterday's big deal is HyperCard's "no big deal."

These tools are much more fleshed out than they first appear, as modifier keys unlock all kinds of helpful variants. Hold down SHIFT while drawing with the pencil tool to constrain it horizontally or vertically. Hold down OPTION while using the brush tool to invert its usage into erasure. And so on.

The tool palette itself "tears off" from the menu and is far more useful in that state. Double-clicking palette icons reveals yet further tricks: the pencil tool opens "fat bits" mode, the eraser clears the screen. The Handbook devotes over 80 pages to the drawing functions. I'll just say that if you can think it, you can draw it.

Remember two gotchas: there's only one level of undo, and all freehand drawing happens in a single layer. The pixels you put down overwrite the pixels that are there, period.

The inclusion of a full paint program makes it really fun to have an idea, sketch it out, see how it looks, try it, and seamlessly move back and forth between art and design tools (and coding tools). The ease of switching contexts feels natural and literal sketches instantly become interactive prototypes. Or final art, if you like! Who am I to judge?

It's kind of startling to be given so much freedom in the tools. As an aside, I took a quick peek at modern no-code editor AirTable and tried to build a simple address book. Beyond the mandatory signup and frustration I felt poking around the tools, I wasn't allowed to place a header graphic without paying a subscription fee. Progress!

Putting a button on it

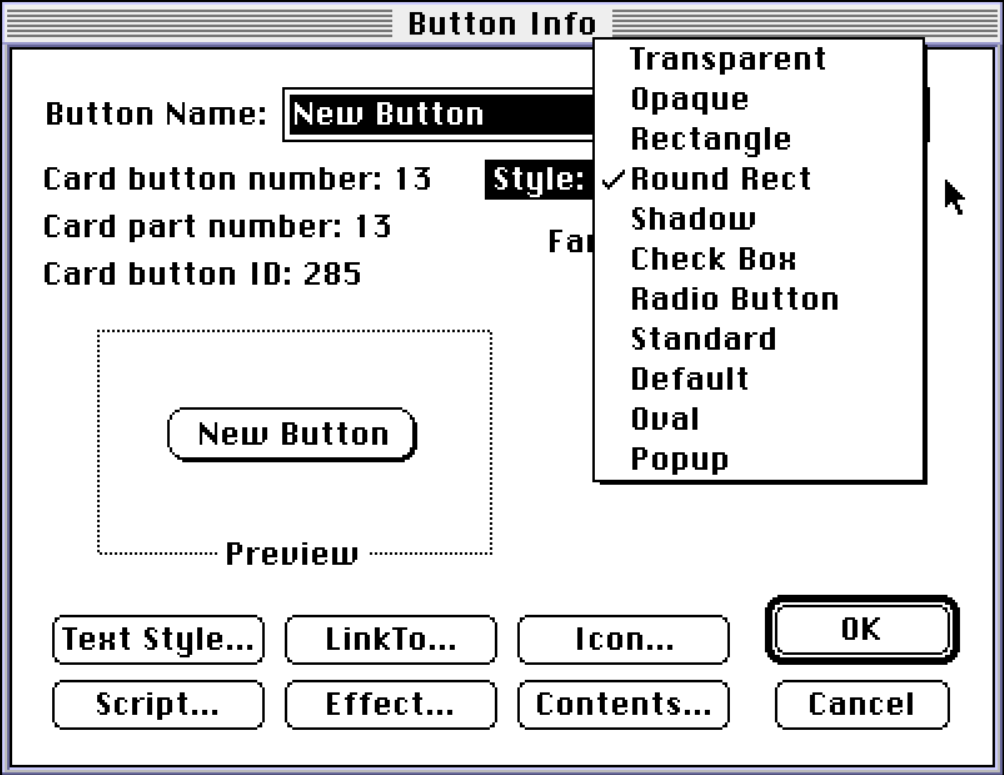

What is hypermedia without hyperlinks? In HyperCard these are implemented as buttons, and if you've ever poked around in Javascript on the web, you already have a good "handle" (wink wink) on how they work. Like text fields, they have a unique ID, a visual style, and can trigger scripts. Remember, HyperCard debuted with scripting in 1987 and similar client-side scripting didn't appear in web browsers until Netscape Navigator 2.0 circa 1995. This was bleeding edge stuff.

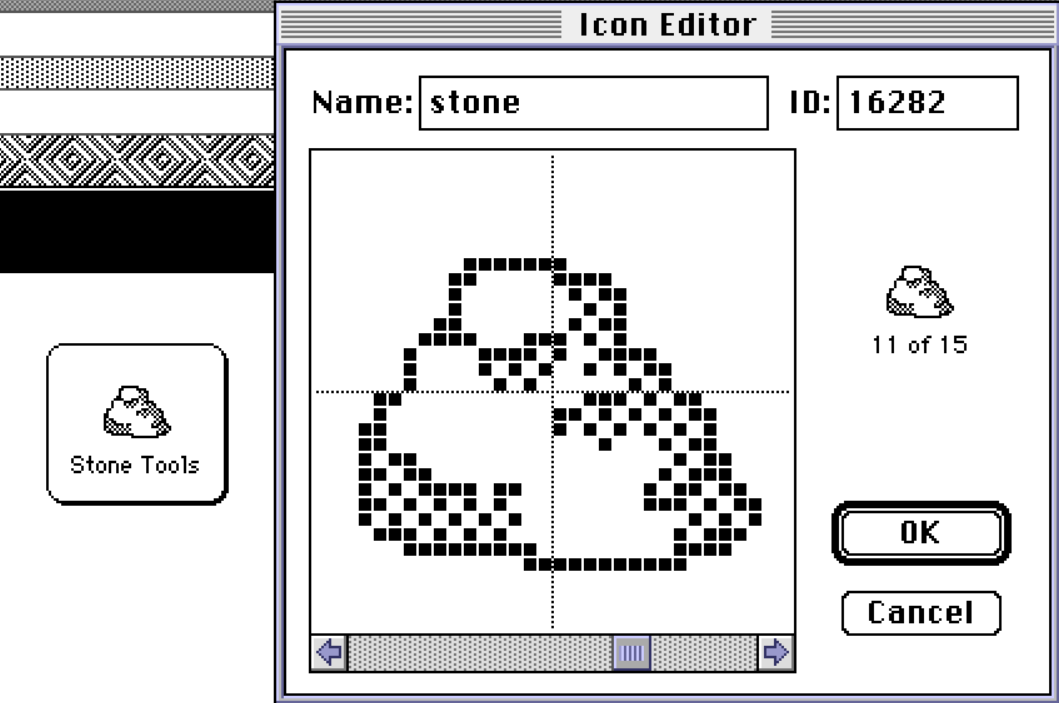

Script..., including even a transitional animation (Effect...).Adding an icon to a button is a little weird, thanks to classic Macintosh "resource forks." All images are stored in this special container, located within the stack file itself. You can't just throw a bunch of images into a folder with a stack and access them freely. Like the lack of multiple undo, this requires a bit of "forget what you know, visitor from the future."

Knowing icon modification is a pain in the butt, Atkinson helpfully added an entire icon editor mini-program to HyperCard. Typically you would have to modify these using ResEdit, a popular, free tool from Apple which allowed users to visually inspect an application's resource fork. Here's a 543 page manual all about it. (Were authors paid by the cubic centimeter back then?)

With ResEdit, all sorts of fun things could be tweaked in applications and even the Finder. You could redraw icons shown during system level alerts and bomb events, or the fill patterns used to draw progress bars. You could hide or show menus in an application, change sound effects, and more. It's dangerous territory, screwing around with system resources, but it's kind of fun because its dangerous. Hack the system!

Buttons can be styled in any number of normal, typical, Macintosh-y ways, but can also be transparent. A transparent button is just a rectangle defining a "hotspot" on the screen, especially useful on top of an image which already visually presents itself as "clickable." To add a hyperlink to text, draw a transparent button on top of that text, wire it up, and you're done. I imagine you can already see the problem.

Rewrite the text.

Now you have to manually reposition your button to overlay the new position of the rewritten text which will last for exactly as long as the text never gets moved or edited. Sure hope the text didn't split onto two lines during the move.

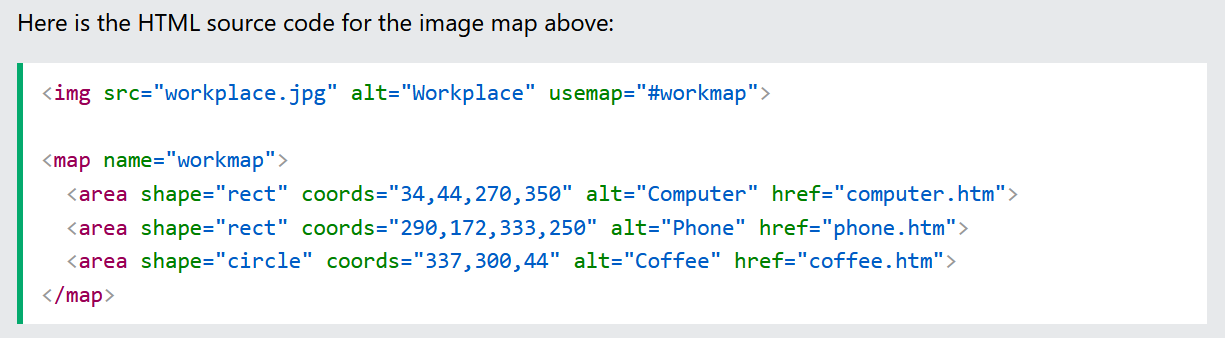

HyperCard does have a sneaky way to fake this up programmatically, but HTML hyperlinks in text would prove to be an unquestionable improvement. Yet, HyperCard speeds ahead of yet-to-arrive-HTML once more with image hyperlinks.

Draw or paste in a picture, say a map of Europe, then draw transparent buttons directly on top of each country. When you're done, it looks like a normal map, but now has clickable countries, which could be directed to transition with a wipe to an information page about the clicked country without ever touching a script.

HyperCard's links are a little brain-dead to be sure, but they are also conceptually very, very easy to grasp. What I really enjoy about the HyperCard approach is how it leverages existing knowledge of GUIs and extends that a little into something familiar yet significantly more powerful.

From the book, "Most viewers of Macintosh applications sense a certain depth or three-dimensionality to many of the images that appear on the screen. Even the pull-down menus have an overlapping feeling when they appear on the screen. Most of the time, this effect is caused by what is called a drop shadow."

Sound of silence

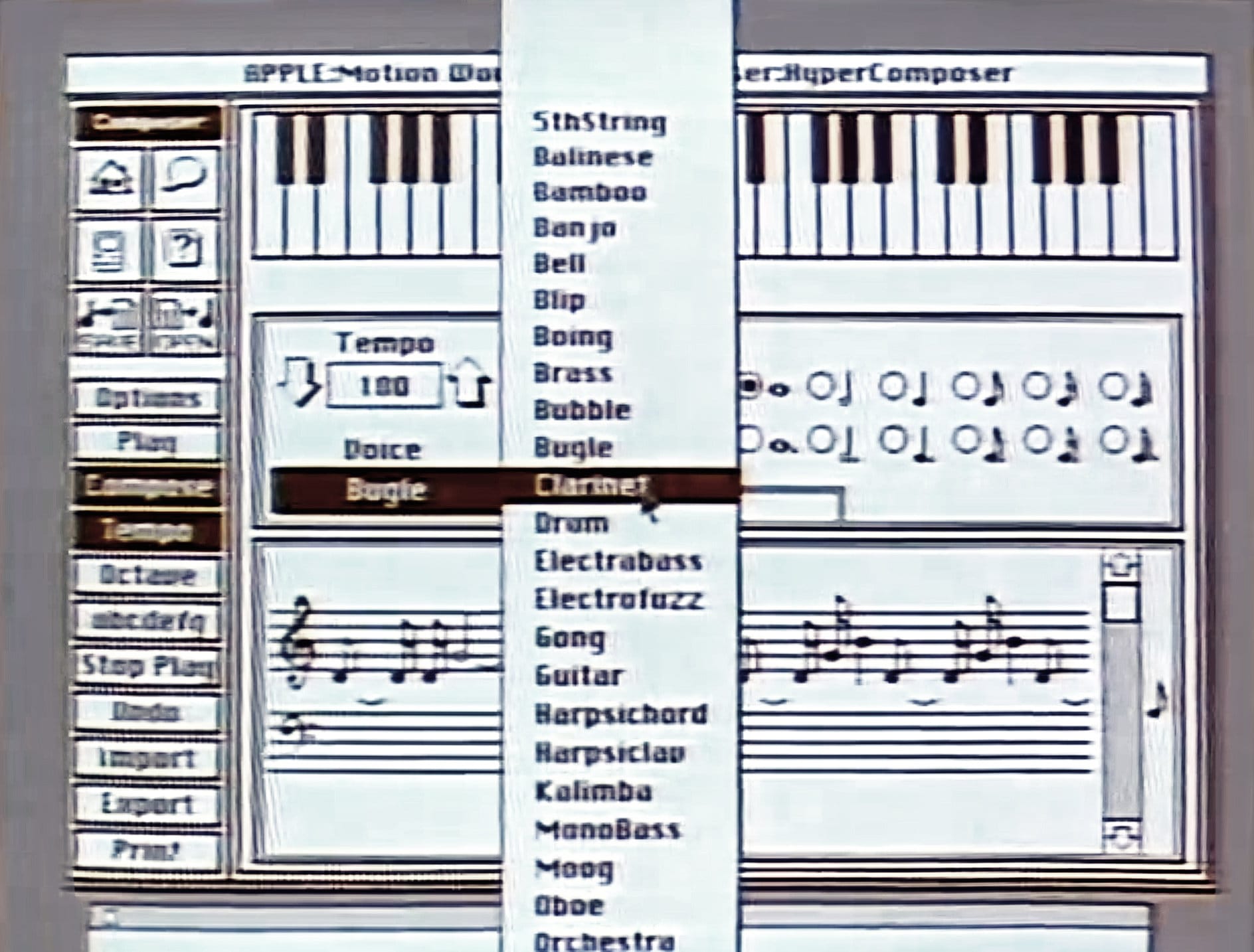

This may be the biggest gap in HyperCard's tool-set. This is not to say that sound effects are completely missing, but they are not given nearly the same thoughtful attention as graphics and scripting are. For reference, where graphics get 80+ pages in the manual, sound gets less than 10.

You can only attach sound effects to your cards through scripting. That can be simple beeps, a sequence of notes in an instrument voice, or a prerecorded sound file. Given the lavish set of tools for drawing, I did honestly expect to have at minimum a piano keyboard for inputting simple compositions.

There were music-making stacks to assist with simple compositions, shunting off responsibility to third party software. That's not a crime, per se, but does feel like a noteworthy gap in an otherwise robust tool-set.

Raison d'etre

In the manual, a no-code tutorial builds a custom Daily To-Do stack, with hyperlink buttons, searchable text, and custom art in just 30 pages. By the end of the tutorial the user has hand-crafted a useful application to personal specifications, which can even be shared with the world, if desired. Not a bad day's work, and I'd be hard-pressed to duplicate that feat today, to be perfectly honest.

This is a deeply empowering program. Even with just 30 minutes of work the user has the beginnings of something interesting. The gap between the user's daily apps and what she's able to build in a weekend at least feels smaller than the gap between 10 PRINT "Hello World" and her daily drivers. Success looks achievable.

You can do things with it almost immediately and you can do sort of sexy things. Graphics, animation, and sound. You get immediate feedback, so you get to see it or hear it immediately. It just feels good, it's fun.

- Jan Lewis, 1990 HyperCard episode,

Computer Chronicles

To-do lists, address books, recipe cards, and the like are all well and good, but every artist eventually feels that urge to push forward and move beyond. At this point I'm only 1/3 through the book so what could the other 600 pages possibly have to talk about? The same thing the rest of this post will: programming.

Wait, wait, come back!

I know, I know, for a lot of people this is a boring, obtuse topic. Believe me, I understand. A lot of people were put off by programming until HyperCard made it accessible. In the January 1988 Compute Magazine (Leemon's rant shows up a few months later), David D. Thornburg noted, "it proves that the proper design of a language can open up programming to people who would never think of themselves as programmers."

This is backed up by firsthand quotes during HyperCard's 25th anniversary

Happy birthday Hypercard!!! This weekend is the 25th Anniversary of HyperCard, my first step in the mac programming world!

- Geppy

Coming up with ideas, and easily implementing them with Hypercard certainly influenced my lifelong interest in programming

- Alex Seville

25 years ago I was so inspired by Bill Atkinson’s demo of HyperCard, I dropped everything and became a Mac programmer

- Andrew Stone

The fact is, if you've poked around in HyperCard at all you've already been programming, you just didn't know it. We call it "no-code" now, though I'd argue HyperCard is more like a coding butler. There is code, you just aren't required to write it for many common tasks.

"No code" only applies to you, the end-user. HyperCard is programming on your behalf.

on learnProgramming

HyperTalk, Dan Winkler's contribution to the project, is HyperCard's bespoke scripting language. Patterned after Pascal, a popular development language for the Macintosh at the time (Photoshop was originally developed in Pascal), HyperTalk was designed be as easy to read and write as possible. In so doing, it attempts to tear down the gates of programming and offer equal access to its community.

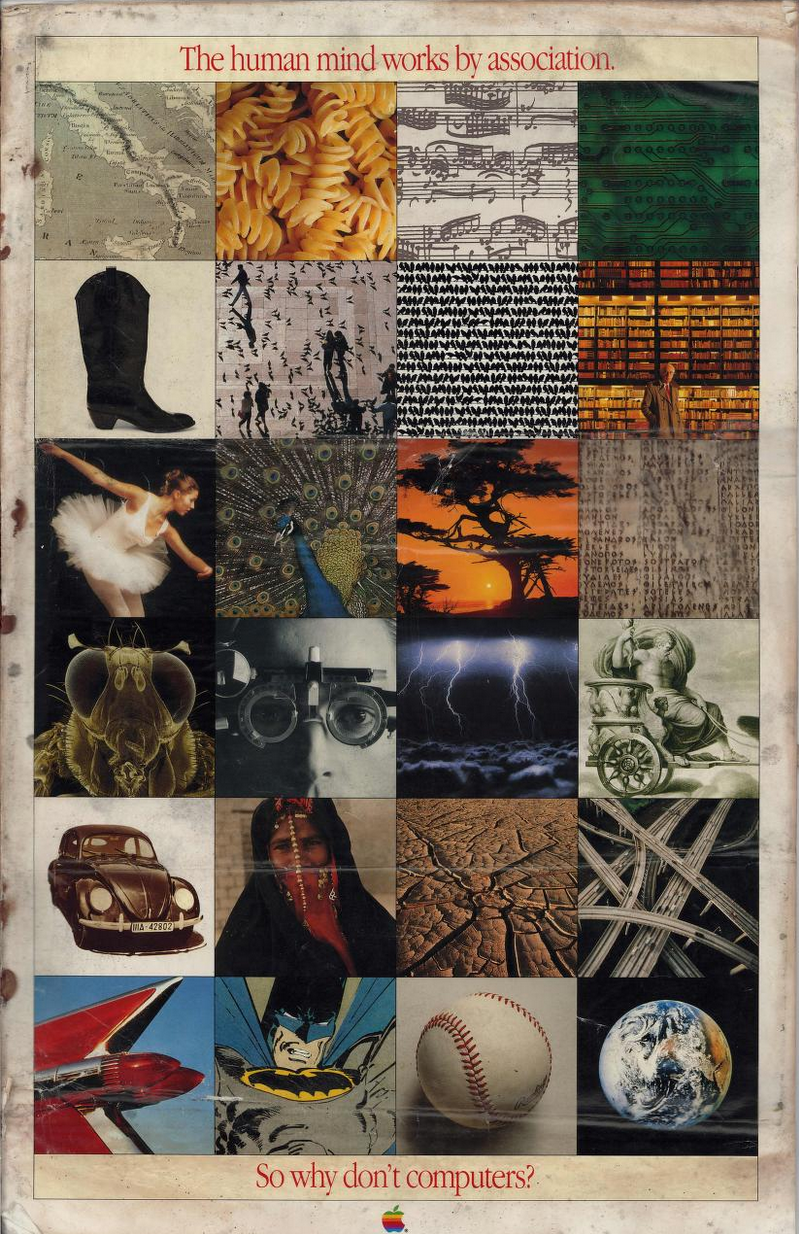

At its core, HyperCard is a collection of objects which send and receive messages. HyperTalk takes an object-oriented approach to stack development.

There are four types of HyperCard objects: stack, card, button, and text field. Let's consider the humble button. A button can receive a message, like "the user clicked the mouse on me." When that occurs, the button has an opportunity to respond to that message in some fashion. Maybe it displays a graphic image. Maybe it plays a sound. Maybe it sends its own message to a different object to do something else.

Scripts define when and how objects process messages. In HyperCard's visual editor, scripts are kind of "inside" objects. Double-click a button to poke at its internal anatomy, with the script being its "brain."

Even if you don't know how to write a HyperTalk script, you can probably read it without much difficulty.

on mouseUp

beep

end mouseUpBaby steps. Pressing a button on your mouse moves that button physically "down," and lifting your finger allows it to move back "up." So this script says "when the mouse button is released, beep."

Want three beeps?

beep 3

Forget the beeps, let's go to the next card of this stack.

go to the next card of this stackNo, not this stack, go to the last card of a different stack.

go to the last card of the stack "Stone Tools"Want to add a visual transition using a special effect and also do the other stuff?

on mouseUp

visual effect checkerboard very slowly

beep 3

go to the last card of the stack "Stone Tools"

end mouseUpThis compositional approach to development helps build skills at a natural pace. Add new behaviors as you learn and see the result immediately. Try new stuff. Tinker. Guess at how to do something. Saw something neat in another stack? Open it and copy out what you like. Experiment. Share. Play.

HyperCard wants us to have fun. I am having fun.

Queen's English-ish

HyperTalk provides fast iteration on ideas and allows us to describe our intent in similar terminology as we have learned over time as end-users. The perceived distance between "desire" and "action" is shortened considerably, even if this comes with unexpected gotchas.

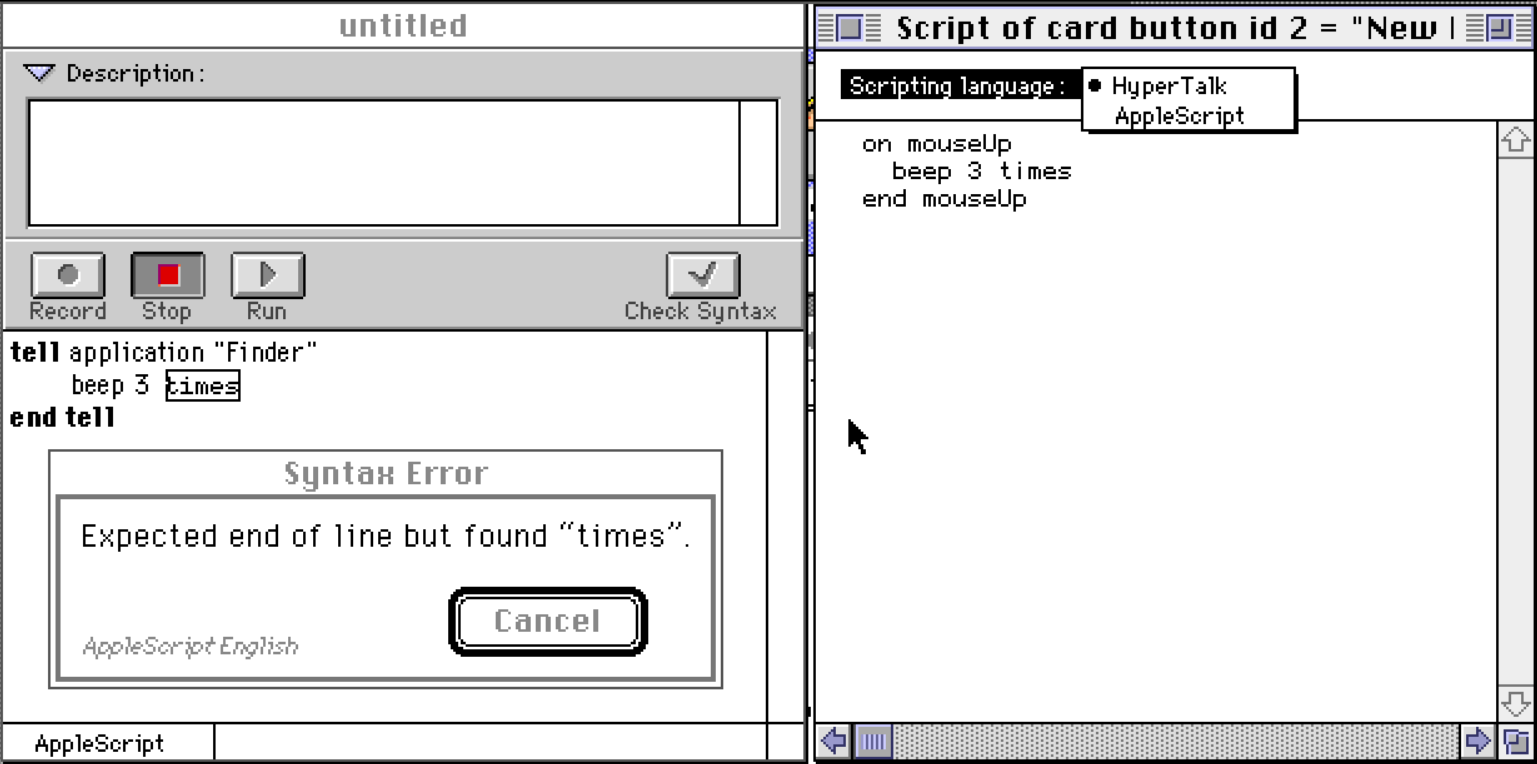

The big gotcha can be a bit of a rude awakening, as English-ish languages tend to be. At first, they seem so simple, but in truth they are not as flexible as true natural language. Going back to the earlier examples, can you intuit which of the following will work and which will error?

on mouseUp

beep 3 times

end mouseUpon mouseUp

very slowly visual effect checkerboard

go to the next card

end mouseUpon mouseUp

repeat 3 times

beep

end repeat

end mouseUpThey all seem reasonable, but only the third one works. This is where the mimicry of English fails the language, because English-ish suggests to a newcomer a free-form expression of thought which HyperTalk cannot hope to understand.

Programmers understand that function names and the parameters which drive them are necessarily rigid and ordered. A more programmer-y definition of the visual effect command might be

void visualEffect(EffectType type, EffectSpeed speed)

|----------------| |-------------| |---------------|

command type speedThus exposed, those familiar with typical coding conventions will immediately understand that HyperTalk (often) requires a similarly specific order of parameters to a command. We can't do this.

very slowly visual effect checkerboard

|---------| |-----------| |----------|

speed command typeWe must rather adhere to the language's hidden order.

visual effect checkerboard very slowly

|-----------| |----------| |---------|

command type speed HyperCard comes with help documentation in the form of searchable stacks, complete with sample scripts to test and borrow from as one grows accustomed to its almost-English sensibilities. Still, it can absolutely be frustrating when something that appears to be valid, like beep 3 times, fails.

Editorial intent

Another knock against HyperTalk's implementation in HyperCard is the code editor itself. It is so bare-bones I thought I had missed something when installing the program. It will format your code indentation, and that's it. At no point will you receive any warning of any kind of mistake. It happily accepts whatever you write.

Only upon trying to run a script will errors surface. On the one hand it is fast and easy to write a script and test it. But it is still requires extra steps which could have been avoided had the editor behaved a bit more like Script Editor, the AppleScript development tool bundled with Mac OS. Script Editor watches your back a little more diligently.

Despite the not-quite-English frustrations, it is still comfortably ahead of any other option of the day. The "Hello World" of HyperCard is a fully functional to-do management application. What a good feeling that engenders in a Mac user dipping a cautious toe into development waters. That feeling builds trust in the system and oneself, and maybe, just maybe, grows a desire to keep learning.

Bag of tricks

The full list of things you can do with HyperTalk is too vast to cover. Here's a teensy weensy super tiny overview of a much longer list, just to whet your appetite:

| Command | Effect |

|---|---|

| drag from <point> to <point> [with <modifier key>] | Simulate mouse movement, even while "holding" an option key (for example) |

| click at <point> [with <modifier key>] | Simulate mouse clicking |

| doMenu <menu item> [<menuName/>] [without dialog] | Manipulate an application menu |

| ask <question> | Display a dialog box with a text input |

| repeat <number of times> [times] | Perform a set of actions a number of times |

| wait for <number> [seconds] | Just chill for a number of seconds |

| dial <phone number> | Literally dial the phone and make a call |

| open file <name of file> | Open a file for reading, or make it if it doesn't exist |

| hide menubar | Turn off the ever-present Macintosh menubar |

| choose <tool name> tool | Select a HyperCard tool to start using |

| set the <property> of <object> to <value> | Manipulate any object's properties, visual or otherwise |

A few example properties you can set on objects:

| Object type | Settable properties |

|---|---|

| on a window | rectangle, dithering, visible, scroll |

| while painting | brush, pattern, textFont |

| on a text field | textAlign, textStyle, dontWrap, script |

| on a button | icon, visible, name, style |

A small sampling of some built-in functions:

| Function | What it does |

|---|---|

| the date | The date in 10/30/99 format |

| the long date | The date in Thursday, October 30, 1999 format |

| the log2 of <number> | A number equal to the base-2 logarithm of <number> |

| the clickText | In a text field, the word that the mouse clicked |

| the ticks | How many ticks since the Mac was turned on? At 60 fps, one tick equals 1/60th of a second. |

| the trunc of <number> | Removes the fractional portion of <number> |

You have plenty of boolean, arithmetic, logical, string, and type operators to solve a wide range of common problems. If you're missing a function, write a new function and use it in your scripts the same as any native command. If some core functionality is missing, HyperCard can be extended via XCMDs and XFCNs, which are new commands and functions built in native code. These can do things like add color support, access SQL databases, digitize sounds, and even let you use HyperCard to compile XCMDs inside of HyperCard itself. Real ouroboros stuff that.

Scripting in your scripting so you can script while you script

With HyperCard 2.2, AppleScript was added as a peer development language. At one point, HyperTalk was considered to become not just HyperCard's scripting language, but the system-wide scripting language for the entire Macintosh ecosystem. AppleScript was developed instead, taking obvious cues from HyperTalk, while throwing all kinds of shade on Dave Winer's (that guy again!) Frontier. Ultimately, Frontier got Sherlocked.

AppleScript allows for scripting control over the system and its applications. Here's a sample (circa System 7.5.5)

tell application "Scriptable Text Editor"

select word 5 of paragraph 4 of the first document

set font of selection to "Helvetica"

end tellLike HyperTalk, you can probably understand that even if you can't write it off the top of your head. Through this synergy, external applications can be controlled directly by HyperCard. PageMaker 5.0 even shipped with a HyperCard stack.

In the video below, I'm clicking a HyperCard button, prompting for text, then shoving that text into an external text editor and applying styling.

The elephant in the room

Now, all of this talk about using plain English to program has many of you shouting at the screen. Don't worry, I hear you loud and clear. I agree, we should talk about a modern natural language programming environment. Let's talk about Inform 7.

For those who don't know, Inform has been a stalwart programming language for the development of interactive fiction (think Zork, and other text adventures) for decades. For the longest time, Inform 6 was the standard-bearer and it looked like "real programming code" complete with semicolons, so you know it was "serious."

Object foyer "Foyer of the Opera House"

with description

"You are standing in a spacious hall, splendidly decorated in red

and gold, with glittering chandeliers overhead. The entrance from

the street is to the north, and there are doorways south and west.",

s_to bar,

w_to cloakroom,

n_to

"You've only just arrived, and besides, the weather outside

seems to be getting worse.",

has light;This describes the room to the player, defines where the exits lead, and specifies that the room has light. From the "Cloak of Darkness" sample project.

In the early 2000's, Inform creator Graham Nelson had an epiphany. Text adventure engines have an in-game parser which accepts English language player input and maps it to code. Could we use a similar parser to accept English language code and map it to code?

Natural language as a literal paraphrase of procedural code can suffer from the faults of both, and many programming languages which superficially ape natural language (such as COBOL, or AppleScript) are not convincingly “different” in feel from orthodox coding languages such as C. This may be because they do not contain genuinely linguistic features, but even so, I feel that natural language is easily overlooked as a syntax option in the design of new systems.

- Graham Nelson, "Natural Language, Semantic Analysis, and Interactive Fiction", 2006

Inform 7 is the result of that research and attempts something significantly more dramatic than HyperTalk. Let's see how to describe that same room from earlier.

Foyer of the Opera House is a room. "You are standing in a spacious hall, splendidly decorated in red and gold, with glittering chandeliers overhead. The entrance from the street is to the north, and there are doorways south and west."

Instead of going north in the Foyer, say "You've only just arrived, and besides, the weather outside seems to be getting worse."

The Cloakroom is west of the Foyer.

The Bar is south of the Foyer.I know you might be incredulous, but this is legit Inform 7 code which compiles and plays.

Inform 7 certainly looks far more natural than the mimicry of HyperTalk. This looks like I can have a conversation with the system and it will do what I want.

The Rain Forest is a room.

The player is in The Rain Forest.

The stone is an object. The player has the stone.

If the player has the stone say "Your pocket feels very hot!"Attempt 1. This does not work.

How embarrassing. Let me try that again.

The Rain Forest is a room.

The player is in The Rain Forest.

The stone is an object. The player holds the stone.

If the player holds the stone say "Your pocket feels very hot!"Attempt 2. I have to say "holds" not "has" to give the stone to the player. The "if" section continues to fail.

AHEM!

The Rain Forest is a room.

The player is in The Rain Forest.

The stone is an object. The player holds the stone.

Every turn:

If the player carries the stone:

say "Your pocket feels very hot."Success! Though we had to take a suspiciously programmery approach to get it to work. Also we use "holds" to give the object to the player, but use "carries" to check inventory.

Obviously, emphasis here is it "looks like" I can write whatever I want, but look too hard and the trick of all such systems is revealed: to program requires programming and programming requires structure. Learning how to structure one's thoughts to build a program which works as expected is the real lesson to learn. That lesson can sometimes be obfuscated by the friendly languages.

No, the other elephant in the room!

Alright, alright, I'll talk about vibe coding, but what, realistically, is there to say? It's a new phenomenon with very little empirical evidence to support or refute the claims of its efficacy. One barrier it may remove is of reliance on English as the base language for development tasks. A multi-lingual HyperCard-alike could be something special indeed.

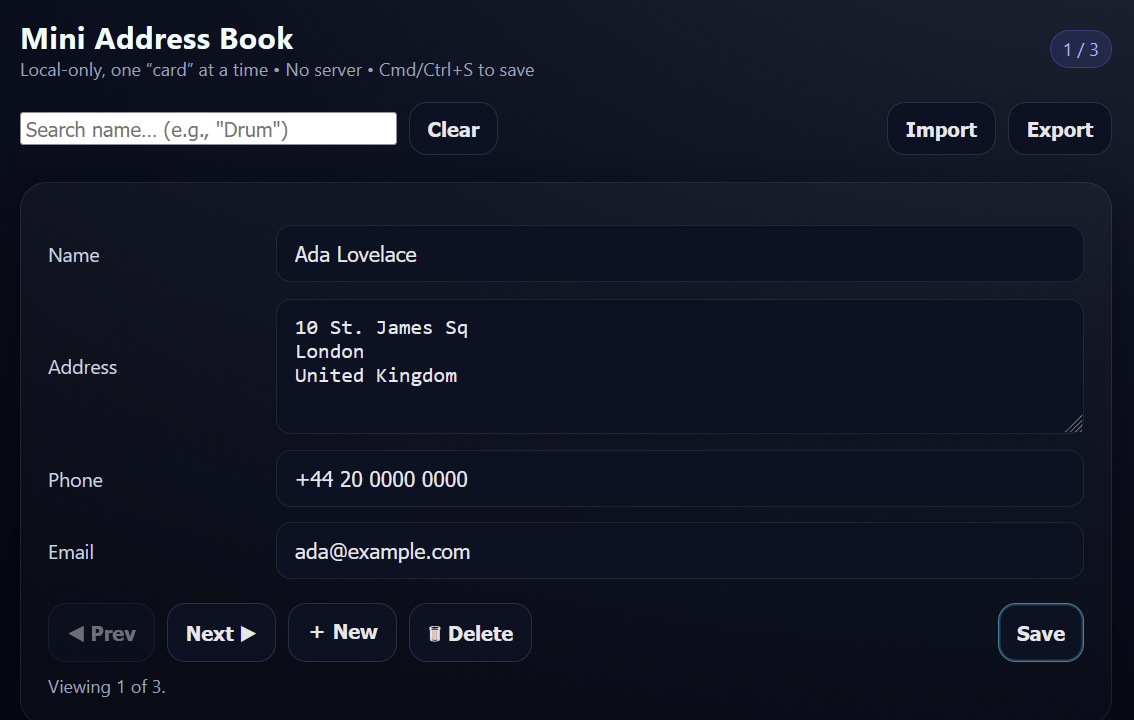

I asked ChatGPT to recreate a HyperCard stack for me in HTML with this prompt.

"In HyperCard it is very simple to set up a custom address book with local storage of data on cards. What is the simplest way to duplicate that in a web browser? Assume one page per entry with name, address, phone number fields. I should be able to step through entries one at a time, or find information by a search, like to find "Drum" in the name field."

Here's the result.

Here's the code.

It seems to work, but I don't know know web development enough to verify it. Nor is there impetus for me to learn to understand it. I could just as easily have asked for this in "the best language for this purpose." Unlike HyperTalk, this approach doesn't ask me to participate in the process which achieved the result, the result itself is all I'm asked to evaluate. When I asked for a change, I receive an entirely different design and layout, but it did contain the functional change. Was that battle won or lost?

I also have no idea how to test this, because my spec was also vibes. I could write a complete spec and ask the LLM to build to that, I suppose. There are people in software development who do exactly that, and they are not called "coders."

This is "vibe product management."

I'm unqualified to determine if that's good enough, but I can say that there is at least one person who seems quite happy with her vibe coding results. While I'm pretty sure her project could be built in HyperCard in an hour, HyperCard doesn't exist. Of course novices like her will turn to LLMs. What other option is there?

I would like to point out, however, that with "vibe coding" we aren't seeing the same Precambrian explosion of new life like we did after HyperCard debuted.

The struggle is real

So I sure have spent a good amount of time talking about the pitfalls and quicksand of using natural language as a programming language. Once we've built simple tools with ease, we quickly learn how much we don't know about programming when we try more advanced techniques. There appears to be a barrier beyond which it makes development harder.

This has been covered by many people over the years.

Dave Winer, of ThinkTank fame, had thoughts on this, "HyperCard was sold this way, as was COBOL. You'd tell the system, in English, what you wanted and it would make it for you. Only trouble is the programming languages only looked superficially like English, to someone who didn't know anything about programming. Once you got into it, it was programming." Yep.

In the February 1998 Compute Magazine, Thornburg concluded his review of HyperCard, "My feeling at this time is that HyperCard lowers the barrier to creating applications for the Mac by quite a bit, but it still requires the discipline and planning required for any programming task." Fair enough.

Edsger W. Dijkstra had thoughts on the matter of natural language as a programming language. He said of this pursuit, "When all is said and told, the "naturalness" with which we use our native tongues boils down to the ease with which we can use them for making statements the nonsense of which is not obvious."

It's true, it can be hard to describe to another human what we want, let alone a computer. We humans are nothing if not walking contradictions, in word and action.

If you'll indulge me, I'd like to issue my bold rebuttal to all of this.

So what?

So what if these languages aren't mathematical rigorous enough for "serious" programming?

So what if they're hard to scale?

So what if we sometimes get caught up in English-ish traps?

So what if using these tools create "bad" (Dijkstra's word) habits which prove hard to overcome?

I'm not naive; I wouldn't run a nuclear reactor on HyperTalk. However, I'm concerned that movements in programming "purity" have also gatekept the hobbyist population.

Thousands of people built thousands of stacks in HyperCard. Businesses were born from it. Work got done. Non-programmers built software that helped themselves or helped other people. Isn't that the whole point of programming, is to help people solve problems? HyperCard and HyperTalk should have set a new baseline for what our computers do right out of the box.

Plot twist

There is a case study of a Photoshop artist working for a major retail advertising department, who didn't know a thing about programming, despite many attempts. It was precisely the English-ish language of AppleScript which finally allowed the principles and structure of programming to "click." He has worked as a professional iOS developer for almost 20 years now. I doubt you're biting your nails in suspense, "Who could this mystery person possibly be?!" It was me.

There is a direct line, a single red thread on the conspiracy cork-board, between my exposure to AppleScript and my current job now an iOS engineer. Seeing people's work become just a little bit easier with the AppleScript tools I built was incredibly gratifying. Those benefits were tangible, measurable. What I built was as real as any "proper" application.

When I outgrew AppleScript, I moved on. Whatever bad habits I had learned, I unlearned. Was this a difficult path toward software engineering enlightenment? Perhaps, but it was my path and it was thanks to tools which were willing to meet me halfway.

Get hyped

I think everyone should absolutely use HyperCard, but probably not for the reason you think. I do not kid myself into believing HyperCard can be a useful daily driver, except for the most tenacious of retro-enthusiast. Like other retro software, if you want to build something for yourself and it's useful, then that's great! But, the browser won the hypertext war, period.

I can quote every positive review. I can enumerate every feature. I can show you stacks in motion, and you wouldn't be wrong to shrug in response. I get it. You're a worldly individual; you've seen it all before.

I don't think you've felt it before, though. HyperCard must be touched to be understood. So do it. Build a few cards, a small stack even, and appreciate how HyperCard's fluidity matches that of human expression. Feel the ease with which your ideas become reality. Build something beautiful.

Now throw it all away.

Then.

Then!

Then you'll understand that the only way to appreciate its brilliance is to have it taken away.

When you're back in present-day, wondering why a 20GB application can't afford the same flexibility as this 1MB dynamo, then you'll understand. "Why can't I change this? Why can't I make it mine?" Such questions will cut you in a dozen small ways every day, until you're nothing but scar tissue. Then you'll understand.

I don't think you'd be reading this blog if you didn't believe, deep down in your core, "things could be better." HyperCard is concrete evidence which supports that belief. And it was created and killed by the same company which voiced precisely the same "things could be better" conviction in their "1984" commercial. Apple called for a revolution.

I'm calling for the next one.

My final "To Do" stack. I went beyond the book and made large, animated daily tabs (a tricky exploration of HyperCard's boundaries, as they exceed the 32x32px max icon size) and a search field.

Sharpening the Stone

I had a lot of trouble setting up my work environment this time around. The primary stumbling block is that Basilisk II, which initially made the whole Mac environment setup easy, has a Windows timing bug which renders HyperCard animations unusably slow.

Mini vMac works great with HyperCard, and feels very snappy, but it couldn't handle a disk over 2GB (I had built a 20GB hard drive for Basilisk II). So I tried to build a new disk image in Mini vMac but it has a weird issue where multi-disk installations "work" except the system ejects the first disk it sees to "accept" the next disk in the install process. That disk was the disk I was trying to install the operating system onto, so the whole endeavor became a comedy of errors. I had to go back into Basilisk II to build a 2GB disk for use in Mini vMac.

Emulator Improvements

- I found 4x speed in the emulator felt very nice; max speed for installations.

- Install the ImportFl and ExportFl utilities for Mini vMac to get data into and out of the virtual Macintosh from your host operating system easily.

Troubleshooting

- The emulator never crashed, though I definitely had troubles with Macintosh apps crashing or running out of memory.

- While I could get the emulator to boot with my virtual hard drive, I couldn't get that to persist during a "system reboot." Maybe there's a setting I overlooked.

- Don't forget to "Get Info" on your apps and manually set their memory usage.

- Extensions enable classic Mac conveniences. I recommend StickyClick, otherwise you have to continuously hold the mouse button down when using menus.

Getting data into the real world

There's not really a foolproof way to do this. HyperCard's stack format has been reverse-engineered and made compatible after-the-fact by a few modern attempts to revive the platform. Importing a stack into a modern platform is possible, as is conversion to HTML. There's going to be a lot of edge cases and broken things during this process, but it's worth it if the stack is awesome. You did build an awesome stack, didn't you?! (I don't think any of these ford the AppleScript river though.)

- Decker looks very much like HyperCard, but looks only. No importing of original stacks and the scripting language is completely different, but that adorable drawing app built in it looks great! Source code for Decker here!

- LiveCode is trying to keep the dream alive in a modern context and can apparently import HyperCard stacks (with caveats). (note: a completely new version, with obligatory AI, went live just a few days before this post!)

- HyperNext Studio might be interesting to some.

- Stacksmith seems to have stalled out in development, but could be fun to play around with.

- HyperCard Simulator looks quite interesting and has a stack importer. 日本語でも使えるよ! I imported Apple's "HyperTalk Reference" stack without issue, though its hyperlinks don't work; I can step through cards. I also see misaligned images and buttons at times, but otherwise it's a great presentation. It can also export a stack to HTML.

- WyldCard, a Java implementation, was updated in 2024. Needs a little knowhow to get your Java build environment set up, and I'm unclear if it can import original stacks.

- hypercard-stack-importer says it will convert a stack to HTML

- UPDATE 12/14/2025: Thanks to Tom Perry in the discussion below, I missed a large open-source project. I thought LiveCode encapsulates all of this, but apparently it is a completely separate project. OpenXTalk works to keep the previous "LiveCode Community Edition" alive, and is also working on a web version called WebTalk Interpreter. I wrote a little HyperTalk as I would for HyperCard, and it ran as expected, no modifications needed.

- UPDATE 2 12/14/2025: Thanks to Bret Victor over on the Mastodon forums for noting I'd overlooked HyperStudio, which had its start on the Apple IIgs. Version 5 is available for Mac and Windows even today (along with Print Shop and Mavis Beacon?!)

What's Lacking?

- Built-in sound support is woeful.

- What you build is essentially constrained to the classic Macintosh ecosystem (though you may find a way to convert the stack; see above)

- The script editor is too bare bones for those who aspire to Myst-like greatness.

- Color support is a 3rd party afterthought.

- Textual hyperlinks can really only be faked through button overlays. It is possible to use HyperTalk to grab a clicked word in a text field, which might be enough context to make a decision upon.

- HyperTalk can be frustrating when implementing advanced ideas. YMMV.

Fossil Record