Scala Multimedia on the Commodore Amiga

It's no Toaster, but it doesn't need to be to hold its own. Possibly one of the most impressive cover disk giveaways in history?

The ocean is huge.

It's not only big enough to separate landmasses and cultures, but also big enough to separate ideas and trends. Born and raised in the United States, I couldn't understand why the UK was always eating so much pudding. Please forgive my pre-internet cultural naiveté.

I should also be kind to myself for thinking the Video Toaster was the be-all-end-all for video production and multimedia authoring on the Amiga. Search Amiga World metadata on Internet Archive for "toaster" and "scala" and you'll see my point. "Toaster" brings up dozens of top-level hits, and "Scala" gets zero. The NTSC/PAL divide was as vast as the ocean.

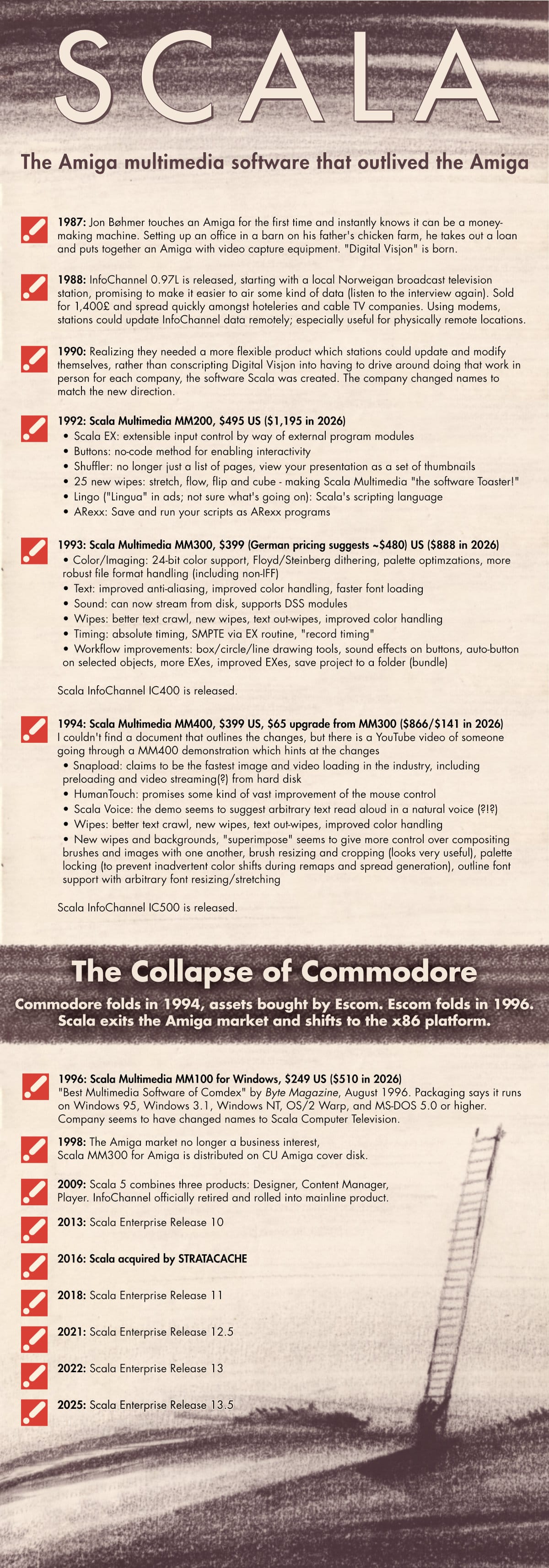

From the States, cross either ocean and Scala was everywhere, including a full, physical-dongle-copy-protection-removed, copy distributed on the cover disk of CU Amiga Magazine, issue 96. Listening to Scala founder, Jon Bøhmer, speak of Scala's creation in an interview on The Retro Hour, his early intuition on the Amiga's potential in television production built Scala into an omnipresent staple across multiple continents.

Intuition alone can't build an empire. Bøhmer also had gladiatorial-like aggression to maintain his dominance in that market. As he recounted, "A Dutch company tried to make a Scala clone, and they made a mistake of putting...the spec sheet on their booth and said all those different things that Scala didn't have yet. So I took that spec sheet back to my developers (then, later) lo and behold before those guys had a bug free version out on the street, we had all their features and totally eradicated their whole proposal."

Now, of course I understand that it would have been folly to ignore the threat. Looked at from another angle, Scala had apparently put themselves in a position where their dominance could face a legitimate threat from a disruptor. Ultimately, that's neither here nor there as in the end, Scala had early momentum and could swing the industry their direction.

Scala (the software) remains alive and well even now, in the digital signage authoring and playback software arena. You know the stuff, like interactive touchscreens at restaurant checkouts, or animated displays at retail stores.

As with the outliner/PIM software in the ThinkTank article, the world of digital signage is likewise shockingly crowded. Discovering this felt like catching a glimpse of a secondary, invisible world just below the surface of conscious understanding.

Scala didn't find success without good reason. It solved some thorny broadcast production issues on hardware that was alone in its class for a time. A unique blend of software characteristics (multitasking, IFF, ARexx) turned an Amiga running Scala into more than the sum of its parts.

Scala by itself would have made rumbles. Scala on the Amiga was seismic.

Historical Context

Testing Rig

- WinUAE v6.0.2 (2025.12.21) 64-bit on Windows 11

- Emulating an NTSC Amiga 1200

- 2MB Chip RAM, 8MB Z2 Fast RAM

- AGA Chipset

- 68020 CPU, 24-bit addressing, no FPU, no MMU, cycle-exact emulation

- Kickstart/Workbench 3.1 (from Amiga Forever)

- Windows directory mounted as HD0:

- For that extra analog spice, I set up the video Filter as per this article

- Emulating an NTSC Amiga 1200

- Scala Multimedia MM300

- Cover disk version from CU Amiga Magazine, issue 96 (no copy protection)

- I didn't have luck running MM400, nor could I find a MM400 manual

- Also using Deluxe Paint IV and TurboText

- Cover disk version from CU Amiga Magazine, issue 96 (no copy protection)

Let's Get to Work

At heart, I'm a print guy. Like anyone, I enjoy watching cool video effects, and I once met Kiki Stockhammer in person. But my brain has never been wired for animation or motion design. My 3D art was always static; my designs were committed to ink on paper. I liked holding a physical artifact in my hands at the end of the design process.

Considering the sheer depths of my video naivete, for this investigation I will need a lot of help from the tutorials. I'll build the demo stuff from the manual, and try to push myself further and see where my explorations take me. CU Amiga Magazine issues 97 - 102 contain Scala MM300 tutorials as well, so I'll check those out for a man-on-the-streets point of view.

The first preconception I need to shed is thinking Scala is HyperCard for the Amiga. It flirts with certain concepts, but building Myst with this would be out of reach for most people. I'll never say it's "impossible," as I don't like tempting the Fates that way, but it would need considerable effort and development skills.

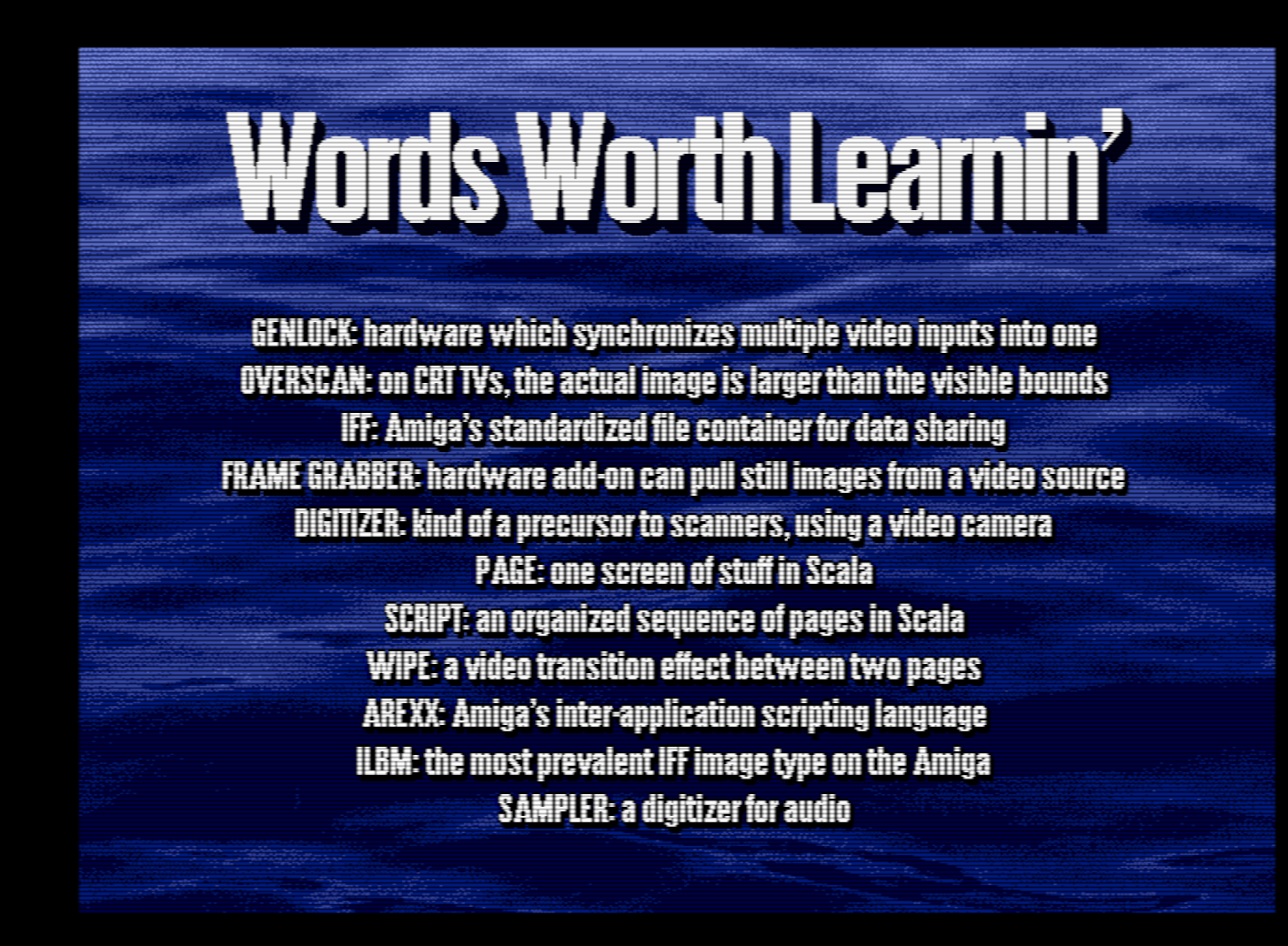

A word, please

A little terminology is useful before we really dig in.

Omakase

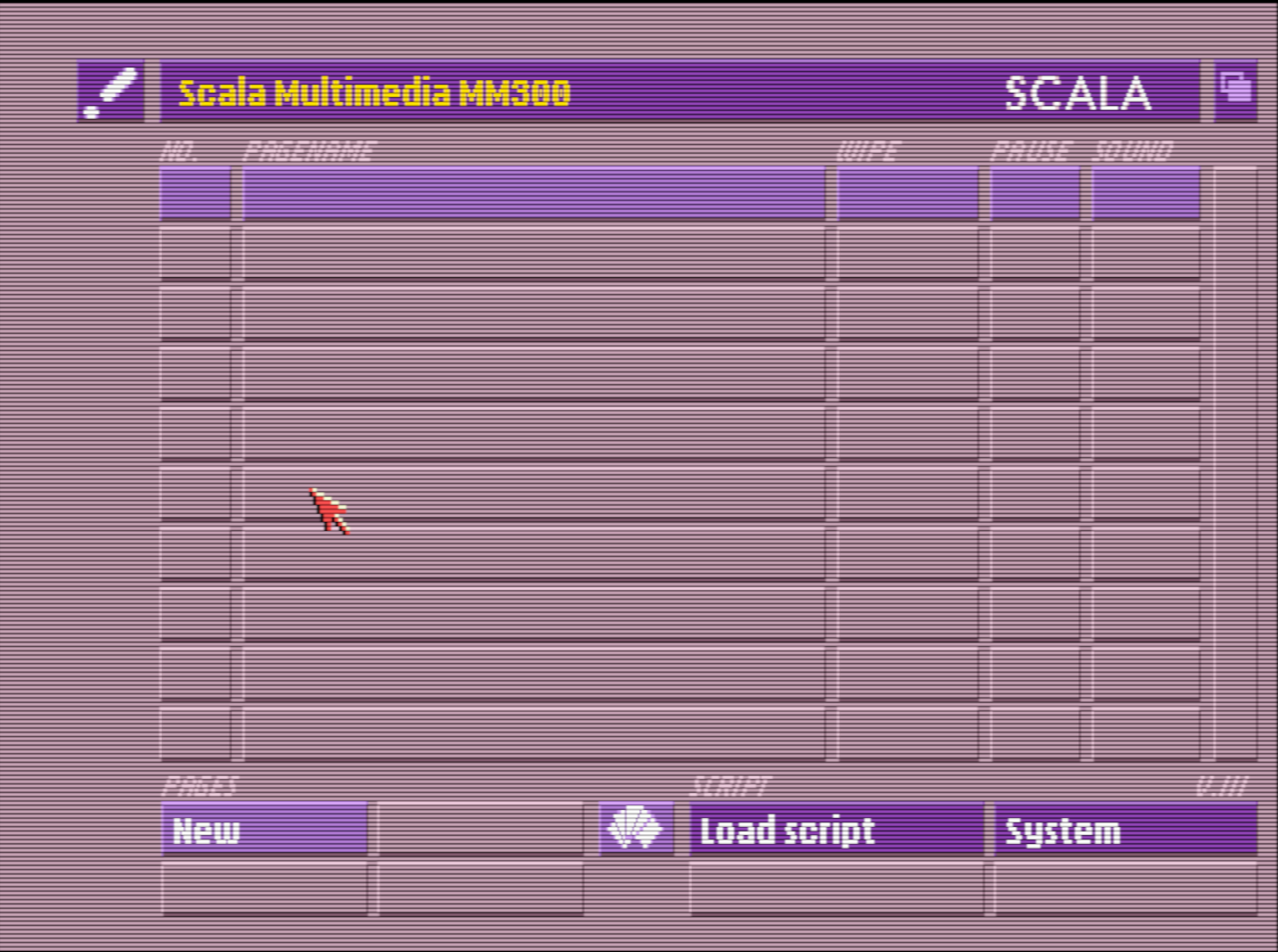

I usually start an exploration of GUI applications by checking out the available menus. With Scala, there aren't any. I don't mean the menubar is empty, I mean there isn't a menubar, period. It does not exist. I am firmly in Scala Land and Scala's vision of how multimedia work gets done.

As with PaperClip, I find its opinionated interface comforting. I have serious doubts about common assumptions of interface homogeneity being a noble goal, but that's a discussion for a future post.

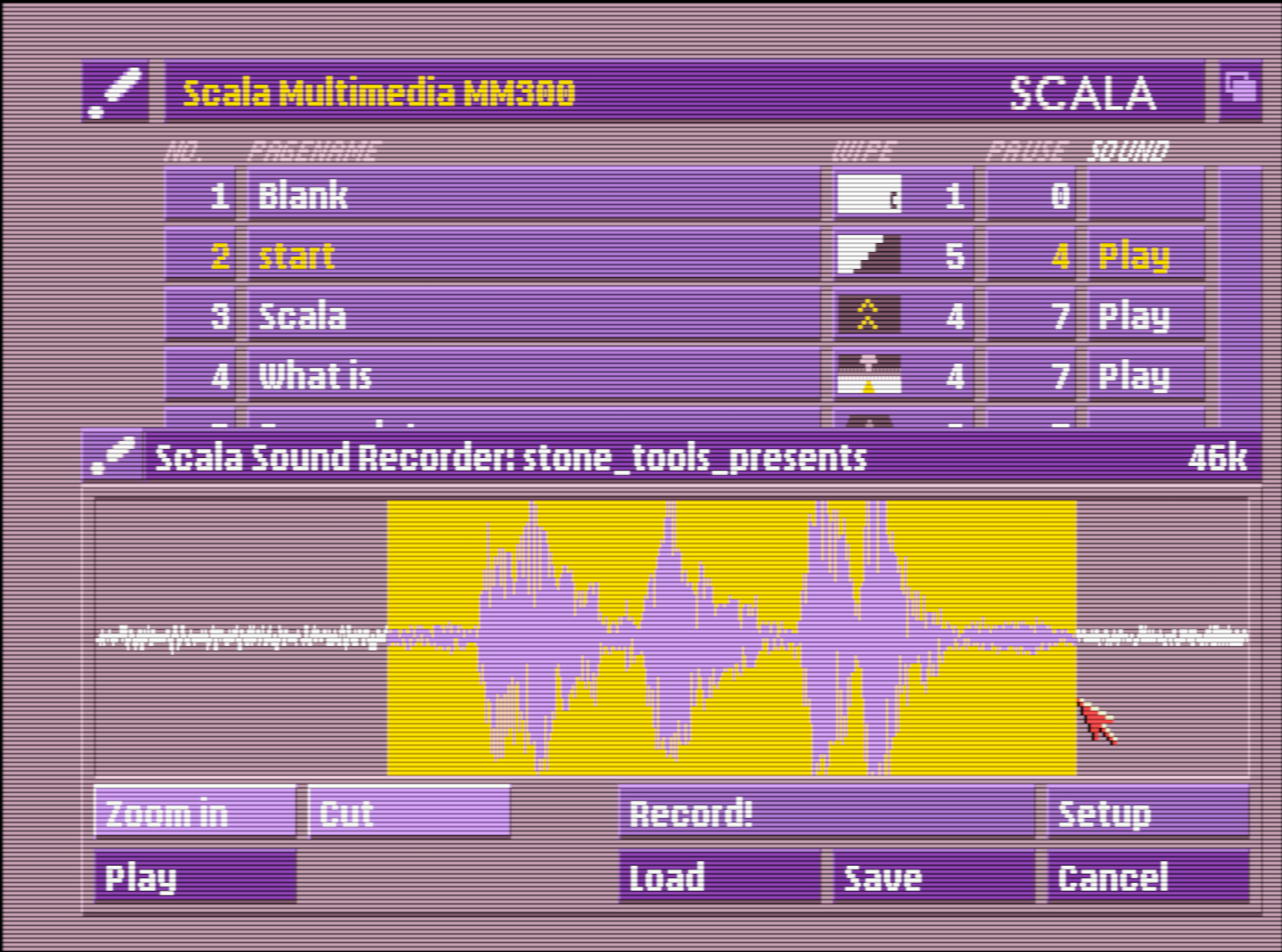

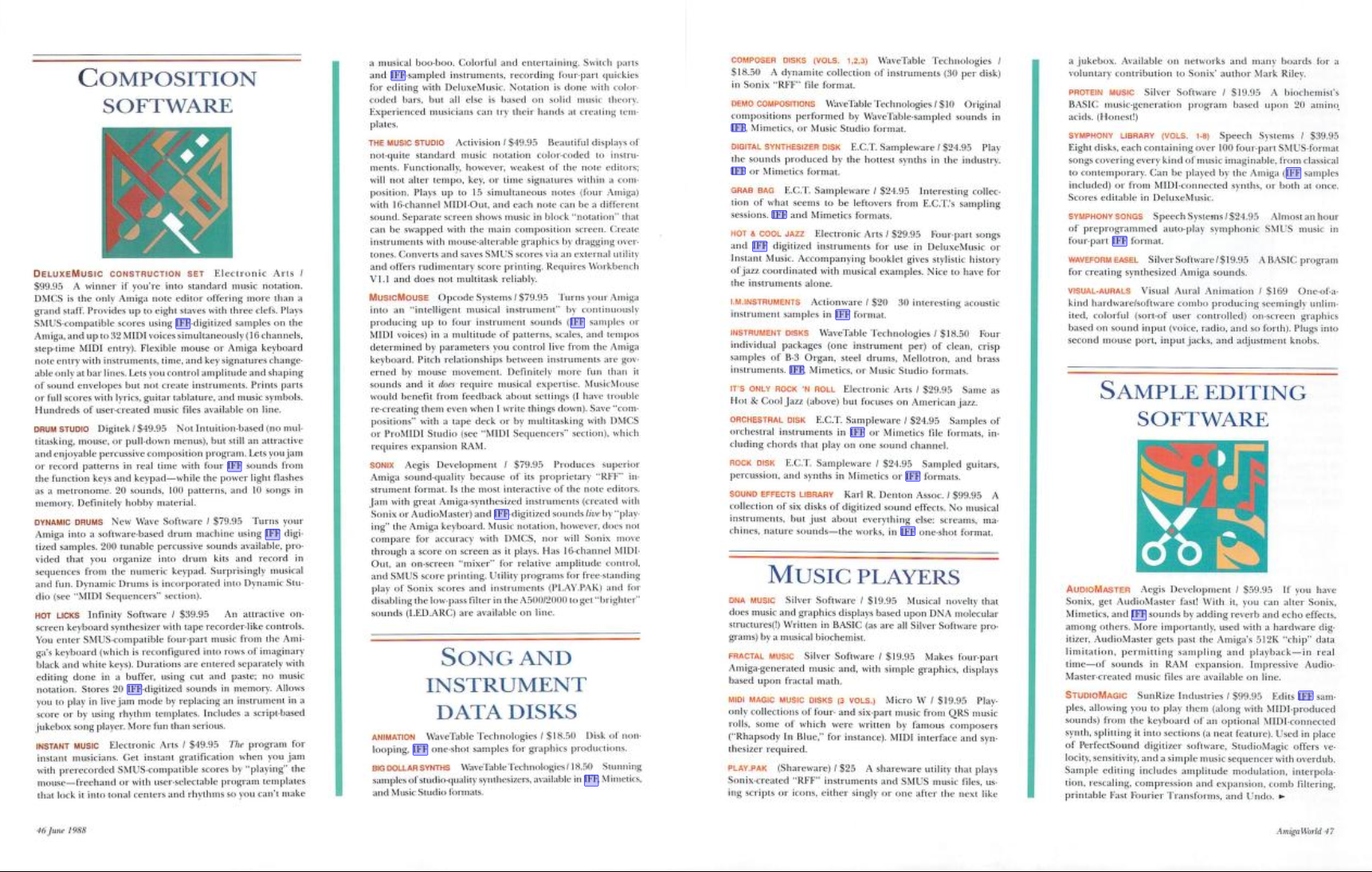

Despite its plain look, what we see when the program launches is richly complex. Anything in purple (or whatever your chosen color scheme uses) is clickable, and if it has its own boundaries it does its own thing. Across the top we have the Scala logo, program title bar, and the Amiga Workbench "depth gadget." Clicking the logo is how we save our project and/or exit the program.

Then we have what is clearly a list, and judging from interface cues its a list of pages. This list ("script") is akin to a HyperCard stack with transitions ("wipes") between cards ("pages"). Each subsection of any given line item is its own button for interfacing with that specific aspect of the page. It's approachable and nonthreatening, and to my mind encourages me to just click on things and see what happens.

The bottom-sixth holds an array of buttons that would normally be secreted away under standard Amiga GUI menus. On the one hand, this means if you see it, it's available; no poking through dozens of greyed-out items. On the other hand, keyboard shortcuts and deeper tools aren't exposed. There's no learning through osmosis here.

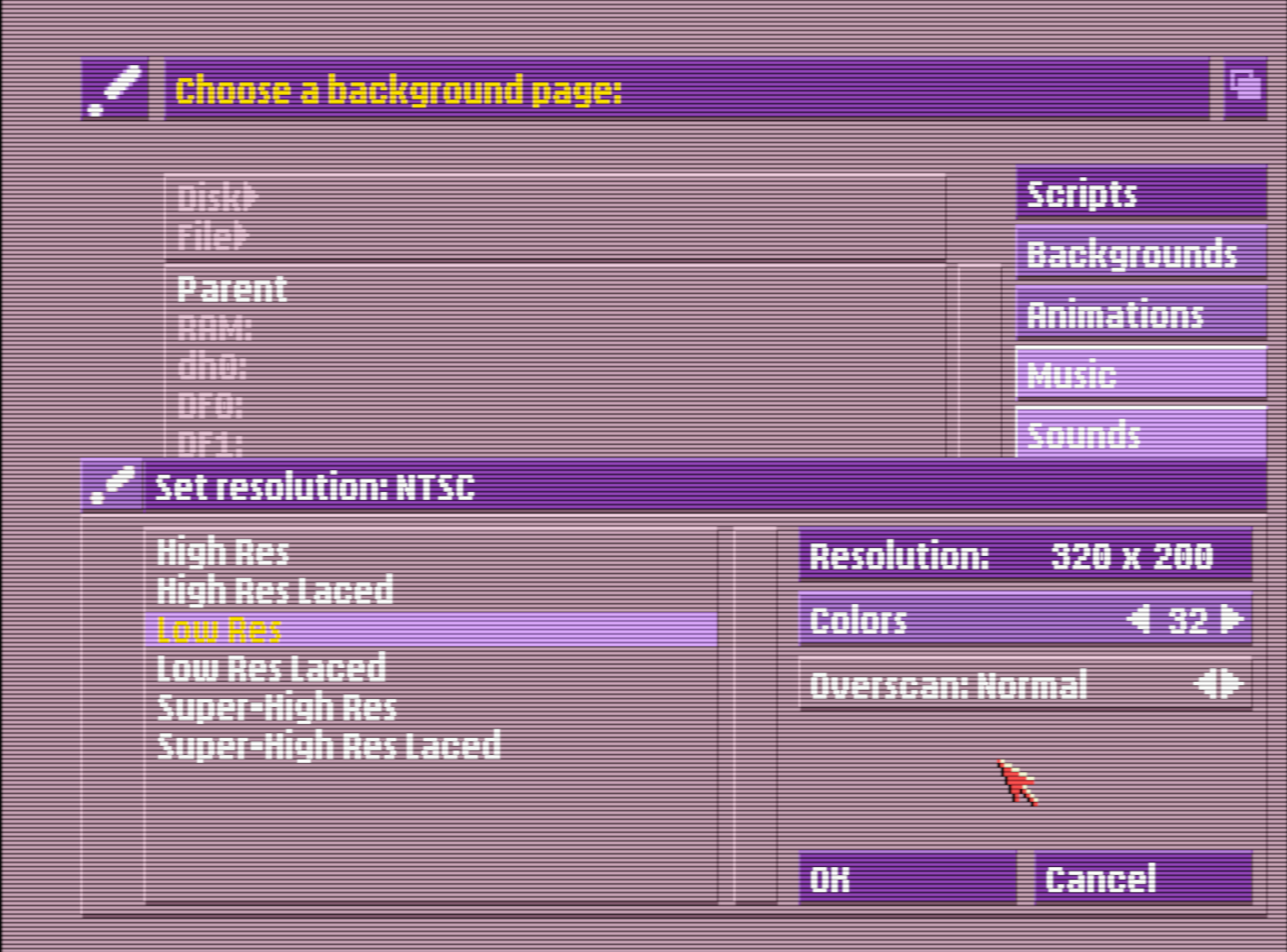

Screen test

Following the tutorial, the first thing to do is define my first "page." Click "New," choose a background as a visual starting point if you like, click "OK", choose a resolution and color depth (this is per-screen, not per-project), and click "OK" to finish. The program steps me through the process; it is clear how to proceed.

The design team for Scala really should be commended for the artistic craftsmanship of the product. It is easy to put something professional together with the included backgrounds, images, and music. Everything is tasteful and (mostly) subdued, if aesthetically "of its time" occasionally. Thanks to IFF support, if you don't like the built-in assets, you can create your own in one of the Amiga's many paint or music programs.

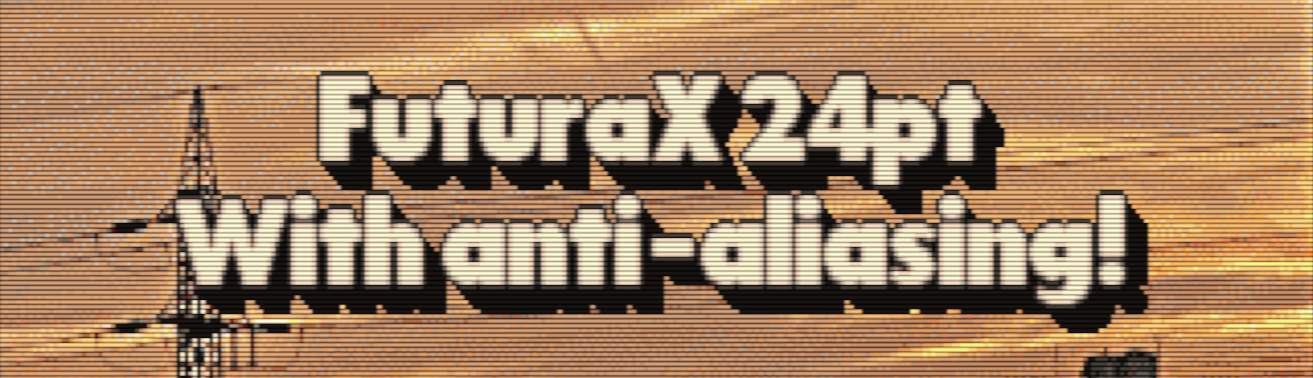

That visual care extends to the included fonts, which are a murderer's row of well-crafted classics. All the big stars are here! Futura, Garamond, Gill Sans, Compact, and more. Hey, is that Goudy I see coming down the red carpet? And behind them? Why it's none other than Helvetica, star of their own hit movie that has the art world buzzing! And, oh no! Someone just threw red paint all over Franklin Gothic. What a shame, because I'm pretty sure that's a pleather dress.

The next screen is where probably 85% of my time will be spent. One thing I've noticed with the manual is a lack of getting the reader up to speed on the nomenclature of the program. This screen contains the "Edit Menu" but is that what I should call this screen? The "Edit Menu" screen? Screen layouts are called "pages." Is this the "Page Edit" screen?

Anyway, the "Edit Menu" gives a lot of control, both fine and coarse, for text styling, shape types, creating buttons, setting the color palette, coordinating object reveals, and more. Buttons with < > hide extra options, for styling or importing other resources, and it could be argued the interface works against itself a bit.

As Scala has chosen to eschew typical Amiga GUI conventions, they walk a delicate line of showing as much as possible, while avoiding visual confusion. It never feels overwhelming, but only just and could stand to borrow from the MacOS playbook's popup menus, rather than < > cycling of options.

Entering text is simple; click anywhere on the screen and begin typing. Where it gets weird is how Scala treats all text as one continuous block. Every line is ordered by Y-position on screen, but every line is connected to the next. Typing too much on a given line will spill over into the next line down, wherever it may be, and however it may be styled.

Text weirdness in the Edit Screen. (I think I had a Trapper Keeper in that pattern.)

The unobtrusive buttons "IN" and "OUT" on the left define how the currently selected object will transition into or out of the screen. Doing this by mouse selection is kind of a drag, as there is no visible selection border for the object being modified. There is an option to draw boxes around objects, but there is no differentiation of selected vs. unselected objects, except when there is. It's a bit inconsistent.

The "List" button reveals a method for assigning transitions and rearranging object timings precisely. It is quickly my preferred method for anything more complex than "a simple piece of text flies into view."

As a list we can define only a pure sequence. Do a thing. Do a second thing. Do a third thing. The end. Multiple items can be "chained" to perform precisely the same wipe as the parent object, with no variation. It's a grouping tool, not a timing tool.

"List" editing of text effect timings. Stay tuned for the sequel: "celeriac and jicama"

I'm having a lot of fun exploring these tools, and have immediately wandered off the tutorial path just to play around. Everything works like I'd expect, and I don't need to consult the manual much at all. There are no destructive surprises nor wait times. I click buttons and see immediate results; my inquisitiveness is rewarded.

Interactive magic

Pages with animation are all good and well, but it is interactivity which elevates a Scala page over the stoicism of a PowerPoint slide. That means it's time for the go-to interaction metaphor: the good ole' button.

Where HyperCard has the concept of buttons as objects, in Scala a button is just a region of the screen. It accepts two events: mouse enter and mouse click, though it burdens these simple actions with the confusing names mark and select. I mix up these terms constantly in my mind.

To add a button, draw a box. Alternately, click something you've drawn and a box bound to that object's dimensions will be auto-generated. Don't be fooled! That box is not tethered to the object. It just happens to be sized precisely to the object's current dimensions and position on screen, as a helpful shortcut to generate the most-likely button for your needs.

Button interactions can do a few things. First, it can adjust colors within its boundaries. Amiga palettes use indexed color, so color swaps are trivial and pixel-perfect. Have some white text that should highlight in red when the mouse enters it? Set the "mark" (mouse enter) palette to remap white to red. Same for "select" (mouse click), a separate palette remap could turn the white to yellow on click. Why am I talking about this when I can just show you?

I intentionally drew the button to be half the text height to illustrate that the button has no relation to the text itself. Color remapping occurs within button boundaries. The double palettes represent the current palette (top), and the remapped palette (bottom).

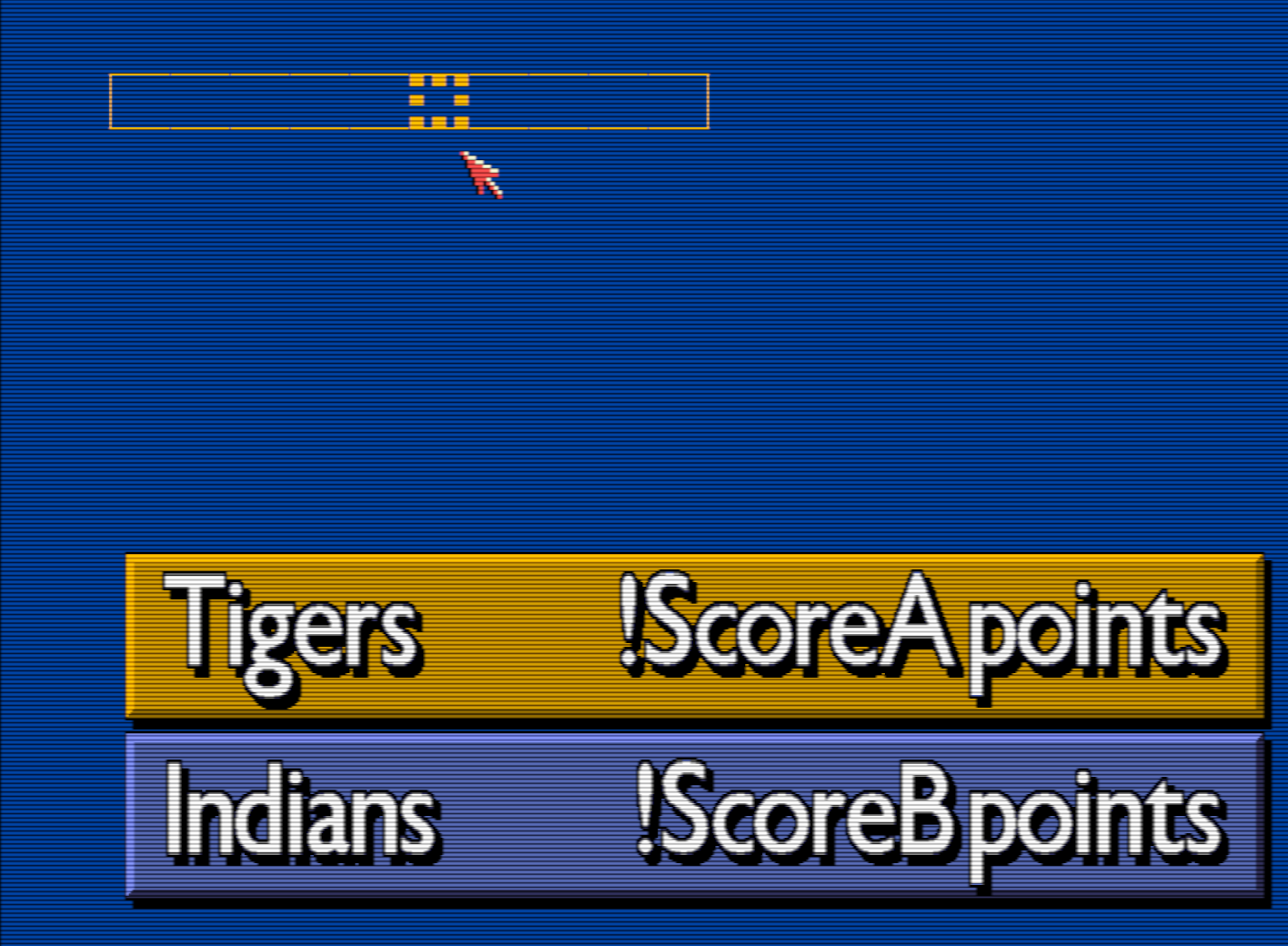

Buttons can also contain simple logic, setting or reading global variable states to determine how to behave at any given moment. IF-THEN statements can likewise be embedded to route presentation order based on those variables. So, a click could add +1 to a global counter, then if the counter is a certain value it could transition to a corresponding page.

If we feel particularly clever with index color palette remapping, it is possible to give the illusion of complete image replacement.

The invisible hand

Buttons do not need any visible attributes, nor do they need to be mouse-clicked to perform their actions. If "Function Keys" are enabled at the Scala "System" level, the first 10 buttons on a page are automatically linked to F1 - F10.

A sample script which ships with Scala demonstrates F-Key control over a page in real-time, altering the values of sports scores by set amounts. This is a clever trick, and with deeper thought opens up interesting possibilities.

If every page in a script were to secretly contain such a set of buttons, a makeshift control panel could function like a "video soundboard" of sorts. F-Keys could keep a presentation dynamic, perhaps reacting to live audience participation. I mention this for no particular reason and it is not a setup for a later reveal. ahem

!ScoreA text shows how variables are ! represented.Script doctor

Once we've made some pages, its time to stitch them together into a proper presentation, a "script" in Scala parlance. This all happens in the "Main Menu" which works similarly to the "List" view when editing page text elements, with a few differences.

"Wipe" is the transition from the previous page to the selected page. If you want to wipe "out" from a page with transition X, then wipe "in" to next page with transition Y, a page must be added in-between to facilitate that.

The quality of the real-time wipe effects surprises me. Again, my video naivete is showing, because I always thought the Amiga needed specialized hardware to do stuff like this, especially when there is video input. The wipes are fun, if perhaps a little staid compared to the Toaster's. In Scala's defense, they remain a bit more timeless in their simplicity.

"Pause" controls, by time or frame count, how long to linger on a page before moving on to the next one. Time can be relative to the start of the screen reveal, or absolute so as to coordinate Scala animations with known timestamps on a pre-recorded video source. A mouse click can also be assigned as the "pause," waiting for a click to continue.

"Sound" attaches a sound effect, or a MOD music file, to the reveal. There are rudimentary tools for adjusting pitch and timing, and even for trimming sounds to fit. An in-built sampler makes quick, crunchy, low-fidelity voice recordings, for when you need to add a little extra pizazz in a pinch, or to rough out an idea to see how it works. Sometimes the best tool for the job is the one you have with you.

New card smell

There are hidden tools on the Main Menu. Like many modern GUI table views, the gap between columns is draggable. Narrowing the "Name" column reveals two hidden options to the right: Variables and Execute.

Now I'm finally getting a whiff of HyperCard.

Unlike HyperCard, these tools are rather opaque and non-intuitive. Right off the bat, there is no built-in script editor. Rather, Scala is happy to position itself as one tool in your toolbox, not to provide every tool you need out of the box. It's going to take some time to get to know how these work, perhaps more than I have allocated for this project, but I'll endeavor to at least come to grips with these.

The Scala manual says, "The Scala definition of variables (closely resembles) ARexx, since all variable operators are performed by ARexx." After 40 years, I guess it's time to finally learn about ARexx.

AWhat?

ARexx is the Amiga implementation of the REXX scripting language. From ARexx User's Reference Manual, "ARexx is particularly well suited as a command language. Command programs, sometimes called "scripts" or "macros", are widely used to extend the predefined commands of an operating system or to customize an applications program."

This is essentially the Amiga's AppleScript equivalent, a statement which surely has a pedant somewhere punching their 1084 monitor at my ignorance. Indeed, the Amiga had ARexx before Apple had AppleScript, but not before Apple had HyperCard.

From the manual, "Double-click: This means to click the left mouse button quickly two times."

Amiga Magazine, August 1989, described it thusly, "Amiga's answer to HyperCard is found in ARexx, a programming and DOS command language, macro processor, and inter-process controller, all rolled into one easy-to-use command language."

"Easy-to-use" you say? Commodore had their heart in the right place, but the "Getting Acquainted" section of the ARexx manual immediately steers hard into programmer-speak.

From the jump we're hit with stuff like, "(ARexx) uses the double-precision math library called "mathieeedoubbas.library" that is supplied with the Amiga WorkBench disk, so make sure that this file is present in your LIBS: directory. The distribution disk includes the language system, some example programs, and a set of the INCLUDE files required for integrating ARexx with other software packages."

I know exactly what I'd have thought back in the day. What is a "mathieeedoubbas?" What is a "library?" Is "LIBS" and "library" the same thing? What is "double-precision?" What is "INCLUDE"? What is a "language system?"

You, manual, said yourself on page 2, "If you are new to the REXX language, or perhaps to programming itself, you should review chapters 1 through 4." So far, that ain't helpin'.

Luckily for young me, now me knows a thing or two about programming and can make sense of this stuff. Well, "sense" in the broadest definition only.

Back to work

What this means for Scala is that we have lots of options for handling variables and logic in our project. The manual says, "Any ARexx operators and functions can be used (in the variable field)." However, a function like "Say," which outputs text to console, doesn't make any sense in a Scala context, so I'm not always 100% clear where lie the boundaries of useful operators and functions.

In addition to typical math functions and simple string concatentation, ARexx gives us boolean and equality checks, bitwise operators, random number generation, string to digit conversion, string filtering and trimming, the current time, and a lot more. Even checking for file existence works, which possibly carried over from Scala's roots as a modem-capable automated remote video-titler.

Realistically, there's only so much we can do given the tiny tiny OMG it's so small interface into which we type our expressions. My aspirations are scoped by the interface design. This is not necessarily a bad thing, IMHO. "Small, sharp tools" is a handy mental scoping model.

Variables are global, starting from the page on which they're defined. So page 1 cannot reach variables defined on page 2. A page can display the value of any currently defined variable by using the ! prefix in the on-screen text, as in !sportsball_score.

I was trying to do Cheifet's melt effect, but I couldn't get animated brushes to work in Scala. Still, I was happy to get even this level of control over genlock/Scala interplay.

Matryoshka

"Execution" in the Main Menu means "execute a script." Three options are available: Workbench, CLI, and ARexx. For a feature that gets two pages in the manual with extra-wide margins, this is a big one, but I get why it only receives a brief mention. The only other recourse would be to include hundreds of pages of training material. "It exists. Have fun." is the basic thrust here.

"Workbench" can launch anything reachable via the Workbench GUI, the same as double-clicking it. This is useful for having a script set up the working environment with helper apps, so an unpaid intern doesn't forget to open them. For ARexx stuff, programs must be running to receive commands, for example.

"CLI" does the same thing as Workbench, except for AmigaDOS programs; programs that don't have a GUI front-end. Maybe open a terminal connection or monitor a system resource.

"ARexx" of course runs ARexx scripts. For a program to accept ARexx commands, it must have an active REXX port open. Scala can send commands, and even its own variable data, to a target program to automate it in interesting ways. I saw an example of drawing images in a paint program entirely through ARexx scripting.

Scala itself has an open REXX port, meaning its own tools can be controlled by other programs. In this way, data can flow between software, even from different makers, to form a little self-enclosed, automation ecosystem.

One unusually powerful option is that Scala can export its own presentation script, which includes information for all pages, wipes, timings, sound cues, etc, as a self-contained ARexx script. Once in that format, it can be extended (in any text editor) with advanced ARexx commands and logic, perhaps to extract data from a database and build dynamic pages from that.

Now it gets wild. That modified ARexx file can then be brought back into Scala as an "Execute" ARexx script on a page. Let me clarify this. A Scala script, which builds and runs an entire multi-page presentation, can itself be transformed into just another ARexx script assigned to a single page of a Scala project.

One could imagine building a Scala front-end with a selection of buttons, each navigating on-click to a separate page which itself contains a complete, embedded presentation on a given topic. Scripts all the way down.

Scala lingo, scala lingo, scala lingo figaro

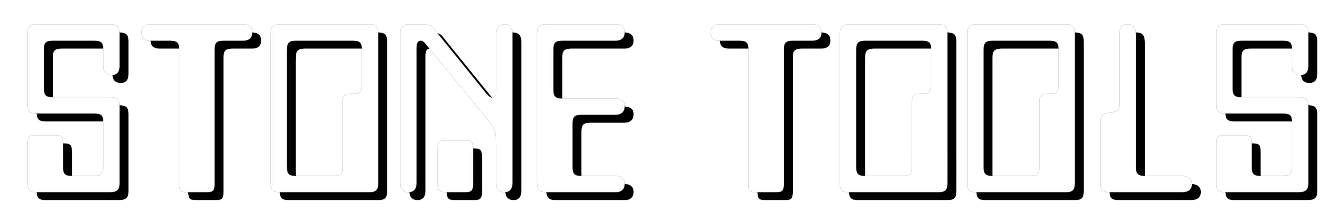

There's one more scripting language Scala supports, and that's its own. Dubbed Scala Lingo (or is it Lingua?), when we save a presentation script we're saving in Lingo. It's human-readable and ARexx-friendly, which is what made it possible to save a presentation as an ARexx script in the previous section.

Here's pure Lingo. This is a 320x200x16 (default palette) page, solid blue background with fade in. It displays one line of white text with anti-aliasing. The text slides in from the left, pauses 3 seconds, then slides out to the right.

V3.0

MOUSE on

FKEYS on

EVENT "page 1"

BLANK 320 200 4 0

WIPE fade speed 5

AACOLOR 038

TABS 50 100 150 200 250

MARGINS on 16 303

PALETTE 038 fff ccc aaa 888 666 444 000 c00 d60 fb0 080 58b 53c a2b f3b

FONT BetonC.font 44

COLOR 1 7 7 7 7 0 1 7 0 1 2 4 7 6 1

ATTRIBUTES remap

STYLE 0 3 4 3 6 1 1 37 5 1 13 0 2 0 1 0 4 4 7

TEXTWIPE dump speed 1

TEXT 15 11 ""

ATTRIBUTES antialias remap center

STYLE 0 3 4 3 6 1 1 37 5 1 13 0 2 2 1 0 4 4 7

TEXTWIPE bob east easeout speed 6

TEXT 54 45 "Stone Tools"

TEXTOUT 2 pause 3

PAUSE -1

ENDHere's the same page as an ARexx script. Looks like all we have to do is wrap each line of Lingo in single quotes, and add a little boilerplate.

/* stonetools:Scala/Scripts/one_page.rexx */

options results

signal on syntax

signal on error

signal on halt

address 'rexx_ScalaMM'

'MOUSE on'

'FKEYS on'

'NUMKEYS off'

'JOYSTICK off'

'POINTER off'

'INTERACTIVE off'

/* page 1 */

'BLANK 320 200 4 0'

'WIPE fade speed 5'

'AACOLOR 038'

'TABS 50 100 150 200 250'

'MARGINS on 16 303'

'PALETTE 038 fff ccc aaa 888 666 444 000 c00 d60 fb0 080 58b 53c a2b f3b'

'FONT BetonC.font 44'

'COLOR 1 7 7 7 7 0 1 7 0 1 2 4 7 6 1'

'ATTRIBUTES remap'

'STYLE 0 3 4 3 6 1 1 37 5 1 13 0 2 0 1 0 4 4 7'

'TEXTWIPE dump speed 1'

'TEXT 15 11 ""'

'ATTRIBUTES antialias remap center'

'STYLE 0 3 4 3 6 1 1 37 5 1 13 0 2 2 1 0 4 4 7'

'TEXTWIPE bob east easeout speed 6'

'TEXT 54 45 "Stone Tools"'

'TEXTOUT 2 pause 3'

'PAUSE -1'

'SHOW'

'CONTINUE'

exit

Syntax:

Error:

Halt:

address 'rexx_ScalaMM'

'SHOW OFF'

exit

Deluxe pain

So, we have Scala on speaking terms with the Amiga and its applications, already a thing that could only be done on this particular platform at the time. Scala's choice of platform was further benefited by one of the Amiga's greatest strengths. That was thanks to the "villain" of the PaperClip article, Electronic Arts.

The hardware and software landscape of the 70s and 80s was a real Wild West, anything goes, invent your own way, period of experimentation. Ideas could grow and bloom and wither on the vine multiple times over the course of a decade. Why, enough was going on a guy could devote an entire blog to it all. ahem

While this was fun for the developers who had an opportunity to put their own stamp on the industry, for end-users it could create a bit of a logistical nightmare. Specifically, apps tended to be siloed, self-contained worlds which read and wrote their own private file types. Five different art programs? Five different file formats.

Data migration was occasionally supported, as with VisiCalc's use of DIF (data interchange format) to store its documents. DIF was not a "standard" per se, but rather a set of guidelines for storing document data in ASCII format. Everyone using DIF could roll their own flavor and still call it DIF, like Lotus did in extending (but not diverging from) VisiCalc's original. Microsoft's DIF variant broke with everyone else, a fact we'll just let linger in the air like a fart for a moment. Let's really breathe it in, especially those of us on Windows 11.

More often than not, especially in the case of graphics and sound, DIF-like options were simply not available. Consider The Print Shop on the Apple 2. When its sequel, The New Print Shop, arrived it couldn't even open graphics from the immediately previous version of itself. A converter program was included to bring original Print Shop graphics into New Print Shop.

On the C64, the Koala file format became semi-standard for images, simply by virtue of its popularity. Even so, there was a market for helping users move graphics across applications on the exact same hardware.

Pain relief

While other systems struggled, programs like Deluxe Video on the Amiga were bringing in Deluxe Music and Deluxe Paint assets without fuss. A cynic will say, "Well yeah, those were all EA products so of course they worked together."

That would be true in today's "silos are good, actually" regression of computing platforms into rent extractors. But, I will reiterate once more, there was genuinely a time when EA was good to its users. They didn't just treat developers as artists, they also empowered users in their creative pursuits.

EA had had enough of the file format wars. They envisioned a brighter future and proposed an open file standard to achieve precisely that. According Dave Parkinson's article "A bit IFFy," in Amiga Computing Magazine, issue 7, "The origins of IFF are to be found in the (Apple) Macintosh's clipboard, and the file conventions which allow data to be cut and pasted between different Mac applications. The success of this led Electronic Arts to wonder — why not generalize this?"

Why not, indeed!

IFF you build it

In 1985, working directly in conjunction with Commodore, the Electronic Arts Interchange File Format 1985 was introduced; IFF for short. It cannot be overstated how monumental it was to unlocking the Amiga's potential as a creative workhorse.

From the Scala manual, "Unlike other computers, the Amiga has very standardized file formats for graphics and sound. This makes it easy to exchange data between different software packages. This is why you can grab a video image in one program, modify it in another, and display it in yet another."

I know it's hard for younger readers to understand the excitement this created, except to simply say that everything in computing has its starting point. EA and the Amiga led the charge on this one.

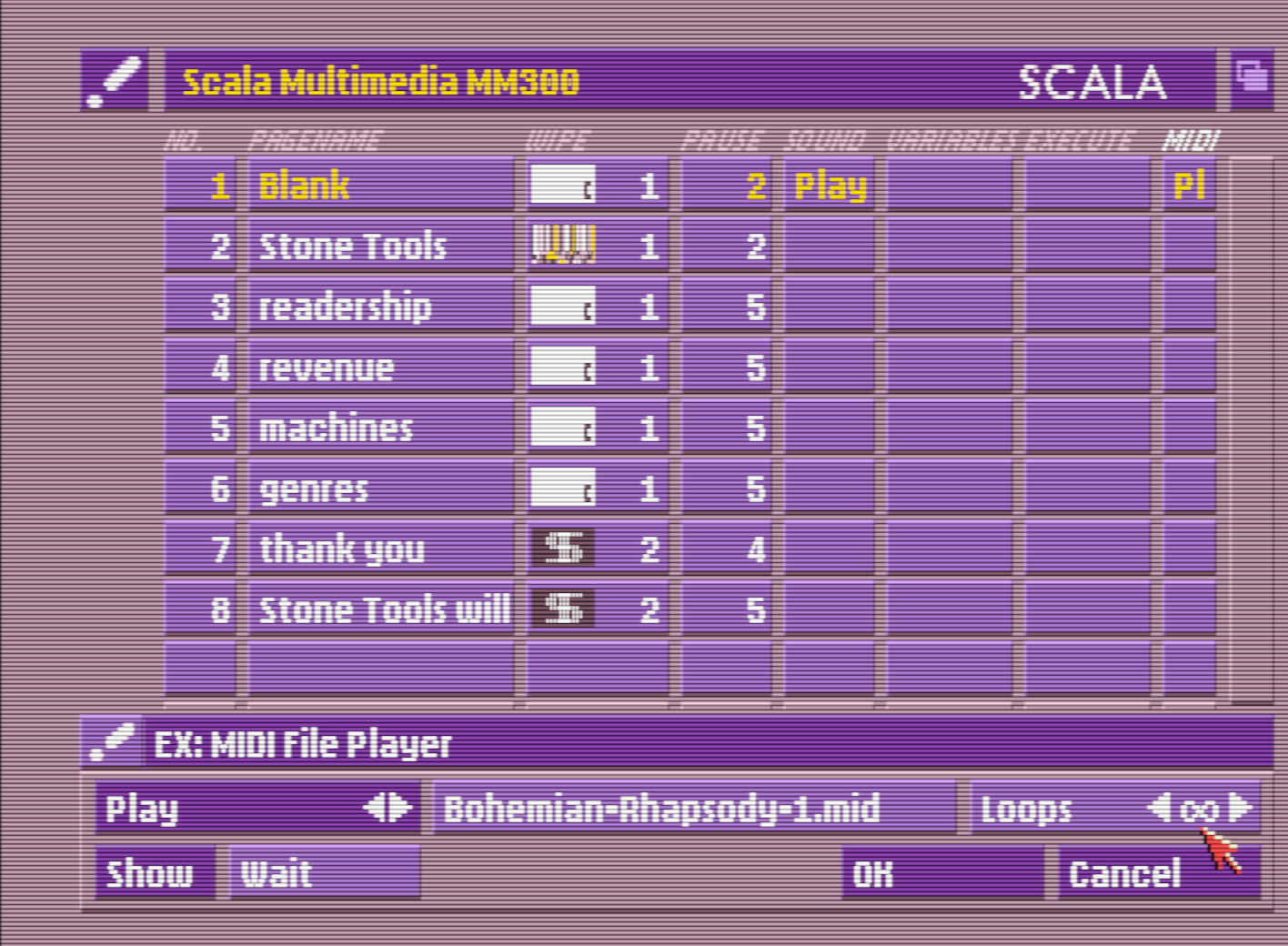

IFF are highlighted in purple. The titles that don't support it are in the minority.What IFF

So, what is it? From "A Quick Introduction to IFF" by Jerry Morrison of Electronic Arts, "IFF is a 2-level standard. The first layer is the "wrapper" or “envelope” structure for all IFF files. Technically, it’s the syntax. The second layer defines particular IFF file types such as ILBM (standard raster pictures), ANIM (animation), SMUS (simple musical score), and 8SVX (8-bit sampled audio voice)."

To assist in the explanation of the IFF file format, I built a Scala presentation just for you, taken from Amiga ROM Kernel Reference Manual. This probably would have been better built in Lingo, rather than trying to fiddle with the cumbersome editing tools and how they (don't) handle overlapping objects well. What's done is done.

I used the previously mentioned "link" wipe to move objects as groups.

IFF is a thin wrapper around a series of data "chunks." It begins with a declaration of what type of IFF this particular file is, known as its "FORM." Above we see the ILBM "FORM," probably the most prevalent image format on the Amiga. Each chunk has its own label, describes how many bytes long it is, and is then followed by that many data bytes. That's really all there is to it. IDs for the FORM and the expected chunks are spec'd out in the registered definition document.

Commodore wanted developers to always try to use a pre-existing IFF definition for data when possible. If there was no such definition, say for ultra-specialized data structures, then a new definition should be drawn up. "To prevent conflicts, new FORM identifications must be registered with Commodore before use," says Amiga ROM Kernel Reference Manual.

In Morrison's write-up on IFF, he likened it to ASCII. When ASCII data is read into a program, it is sliced, diced, mangled, and whatever else needs to be done internally to make the program go. However, the data itself is on disk in a format unrelated to the program's needs. Morrison described a generic system for storing data, of whatever type, in a standardized way which separated data from software implementations.

At its heart, IFF first declares what kind of data it holds (the FORM type), then that data is stored in a series of labelled chunks. The specification of how many chunks a given FORM needs, the proper labels for those chunks, the byte order for the raw data, and so on are all in the FORM's IFF definition document. In this way, anyone could write a simple IFF reader that follows the registered definition, et voila! Deluxe Paint animations are suddenly a valid media resource for Scala to consume.

"File compatibility is easy to achieve if programmers let go of one notion—dumping internal data structures to disk."

- Jerry Morrison, "A Quick Introduction to IFF"

It can be confusing when hearing claims of "IFF compatibility" in magazines or amongst the Amiga faithful, but this does not mean that any random Amiga program can consume any random IFF file. The burden of supporting various FORMS still rests on each individual developer. FORM definitions which are almost identical, yet slightly different, were allowed.

For example, the RGBN image FORM is "almost identical to ILBM" with differences in the BODY chunk and the requirement of a new chunk called CAMG. "Almost identical" is not "identical" and so though both RGBN and ILBM are wrapped in standardized IFF envelopes, a program must explicitly support the ones of interest. Prevalent support for any given FORM type came out of a communal interest to make it standard.

Cooperation was the unsung hero of the IFF format.

"Two can do something better than one," has been on infinite loop in my mind since 1974.

IFF only

How evergreen is that XKCD comic about standards? Obviously, given we're not using it these days, IFF wound up being one more format on the historical pile. We can find vestiges of its DNA here and there, but not the same ubiquity.

There were moves to adopt IFF across other platforms. Tom Hudson, he of DEGAS Elite and CAD-3D, published a plea in the Fall 1986 issue of START Magazine for the Atari ST development crowd to adopt IFF for graphics files. He's the type to put up, not shut up, and so he also provided an IFF implementation on the cover disk, and detailed the format and things to watch out for.

Though inspired by Apple originally, Apple seemed to believe IFF only had a place within a specific niche. AIFF, audio interchange file format, essentially standardized audio on the Mac, much like ILBM did for Amiga graphics. Despite being an IFF variant registered with Commodore, Scala doesn't recognize it in my tests. So, again, IFF itself wasn't a magical panacea for all file format woes.

That fact was recognized even back in the 80s. In Amazing Computing, July 1987, in an article "Is IFF Really a Standard?" by John Foust, "Although the Amiga has a standard file format, it does not mean Babel has been avoided." He noted that programs can interpret IFF data incorrectly, resulting in distorted images, or outright failure.

Ah well, nevertheless.

Side note: One might reasonably believe TIFF to be a successful variant of IFF. Alas, TIFF shares "IFF" in name only and stands for "tagged image file format."

One more side note: Microsoft also did to IFF what they did to DIF. fart noise

Call your EX

The last major feature of note is Scala's extensibility. In the Main Menu list view, we have columns for various page controls. The options there can be expanded by including EX modules, programs which control external systems. This feels adjacent to HyperCard's XCMDs and XFCNs, which could extend HyperCard beyond its factory settings. EX modules bundled with Scala can control Sony Laserdisc controllers, enable MIDI file playback, control advanced Genlock hardware, and more.

Once installed as a "Startup" item in Scala, these show up in the Main Menu and are as simple to control as any of Scala's built-in features. As an EX module, it is also Lingo scriptable so the opportunity to coordinate complex hardware interactions all through point-and-click is abundant.

I turned on WinUAE's MIDI output and set it to "Microsoft GS Wave Table." In Amiga Workbench, I enabled the MIDI EX for Scala. On launch, Scala showed a MIDI option for my pages so I loaded up Bohemian-Rhapsody-1.mid.

Mamma mia, it worked!

I haven't found information about how to make new EXes, nor am I clear what EXes are available beyond Scala's own. However, here at the tail end of my investigation, Scala is suddenly doing things I didn't think it could do. The potential energy for this program is crazy high.

Pivot to video?

No, I'm not going to be doing that any time soon, but boy do I see the appeal. Electronic Arts's documentation quoted Alan Kay for the philosophy behind the IFF standard, "Simple things should be simple, complex things should possible." Scala upholds this ideal beautifully.

Making text animate is simple. Bringing in Deluxe Paint animations is simple. Adding buttons which highlight on hover and travel to arbitrary pages on click is simple. The pages someone would typically want to build, the bread-and-butter stuff, is simple.

The complex stuff though, especially ARexx scripting, is not fooling around. I tried to script Scala to speak a phrase using the Amiga's built-in voice synthesizer and utterly failed. Jimmy Maher wrote of ARexx in The Future Was Here: The Commodore Amiga, "Like AmigaOS itself, it requires an informed, careful user to take it to its full potential, but that potential is remarkable indeed."

While Scala didn't make me a video convert, it did retire within me the notion that the Toaster was the Alpha and Omega of the desktop video space. Interactivity, cross-application scripting, and genlock all come together into a program that feels boundless.

In isolation, Scala a not a killer app. It becomes one when used as the central hub for a broader creative workflow. A paint program is transformed into a television graphics department. A basic sampler becomes a sound booth. A database and a little Lingo becomes an editing suite.

Scala really proves the old Commodore advertising slogan correct, "Only Amiga Makes it Possible."

I'm accelerating the cycle of nostalgia. Now, we long for "four months ago."

BONUS: Streaming like its 1993

The more I worked with Scala, the more I wanted to see how close I could get to emulating video workflows of the day. Piece by piece over a few weeks I discovered the following (needs WinUAE, sorry) setup for using live Scala graphics with an untethered video source in a Discord stream. Scala can't do video switching*, so I'm locked to whatever video source happens to be genlocked to WinUAE at the moment. But since when were limitations a hindrance to creativity?

*ARexx and EX are super-powerful and can extend Scala beyond its built-in limitations, but I don't see an obvious way to explore this within WinUAE.

Step 1: Connect your camera

This is optional, depending on your needs, but its the fun part. You can use whatever webcam you have connected just as well.

Camo Camera can stream mobile phone video to a desktop computer, wirelessly no less. Camo Camera on the desktop advertises your phone as a webcam to the desktop operating system. So, install that on both the mobile device and desktop, and connect them up.

Step 2: Genlock it

WinUAE can see the "default" Windows webcam, and only the default, as a genlock source; we can't select from a list of available inputs. It was tricky getting Windows 11 to ignore my webcam and treat Camo Camera as my default, but I got it to work.

When you launch WinUAE, you should see your camera feed live in Workbench as the background. So far, so good. Next, in Scala > Settings turn on Genlock. You should now see your camera feed in Scala with Scala's UI overlaid.

Step 3: Broadcast as a virtual camera

Now that we have Scala and our phone's video composited, switch over to OBS Studio. Set the OBS "Source" to "Window Capture" on WinUAE. Adjust the crop and scale to focus in on the portion of the video you're interested in broadcasting. On the right, under "Controls" click "Start Virtual Camera." Discord, Twitch, et al are able to see OBS as the camera input for streaming.

When you can see the final output in your streaming service of choice (I used Discord's camera test to preview), design the overlay graphics of your heart's desire. Use that to help position graphics so they won't be cut off due to Amiga/Discord aspect ratio differences.

While streaming, interactivity with the live Scala presentation is possible. If you build the graphics and scripts just right, interesting real-time options are possible. Combine this with what we learned about buttons and F-Keys, and you could wipe to a custom screen like "Existential Crisis - Back in 5" with a keypress.

Headline transitions were manually triggered by the F-Keys, just to pay off the threat I made earlier in the post. See? I set'em up, I knock'em down. I also wrote a short piece about Cheifet, because of course I did.

Sharpening the Stone

Ways to improve the experience, notable deficiencies, workarounds, and notes about incorporating the software into modern workflows (if possible).

Emulator Improvements

- Nothing to speak of. The "stock" Amiga 1200 setup worked great. I never felt the need to speed boost it, though I did give myself as much RAM as possible.

- I'll go ahead and recommend Deluxe Paint IV over III as a companion to Scala, because it supports the same resolutions and color depths.

- If you wind up with a copy of Scala that needs the hardware dongle, WinUAE emulates that as well. Under

Host > IO ports > Protection Dongleare the "red" (MM200) and "green" (MM300 and higher) variants - I'm not aware of any other emulators that offer a Genlock option.

Troubleshooting

- I did not encounter any crashes of the application nor emulator.

- One time I had an "out of chip RAM" memory warning pop up in Scala. I was unclear what triggered it, as I had maxed out the chip RAM setting in WinUAE. Never saw it again after that.

- I did twice have a script become corrupted. Scripts are plain text and human-readable, so I was able to open it, see what was faulting, and delete the offending line. So, -6 points for corrupting my script; +2 points for keeping things simple enough that I could fix it on my own.

- F-Keys stopped working in Scala's demonstration pages. Then, it started working again. I think there might have been an insidious script error that looked visually correct but was not. Deleting button variable settings and resetting them got it working again. This happened a few times.

- I saw some unusual drawing errors. Once was when a bar of color touched the bottom right edge of the visible portion of the screen, extra pixels were drawn into the overscan area.

- Another time, I had the phrase "Deluxe Paint" in Edit Mode, but when I viewed the page it only said "Deluxe Pa". Inspecting the text in "List" mode revealed unusual characters (the infinity symbol?!) had somehow been inserted into the middle of the text.

Getting Your Data into the Real World

- I outlined one option above under "Bonus: Streaming Like Its 1993" above.

- OBS recording works quite well and is what I used for this post.

- WinUAE has recording options, but I didn't have a chance to explore them.

- I don't yet know how to export Scala animations into a Windows-playable format.

What's Lacking?

- For 2026, it would surely be nice to have native 16:9 aspect ratio support.

- Temporary script changes would be useful. I'd love to be able to turn off a page temporarily to better judge before/after flow.

- It can be difficult to visualize an entire project flow sometimes. With page transitions, object transitions, variable changes, logic flow, and more, understanding precisely what to do to create a desired effect can get a little confusing.

- Scala wants to maintain a super simple interface almost to its detriment. Having less pretty, more information dense, "advanced" interface options would be welcome. I suppose that's what building a script in pure ARexx is for.

- I'd like to be able to use DPaint animated brushes. Then I could make my own custom "transition" effects that mix with the Scala page elements. Maybe it's possible and I haven't figured out the correct methodology?

- The main thing I wanted was a Genlock switch, so I could do camera transitions easily. That's more of a WinUAE wishlist item though.

Fossil Record