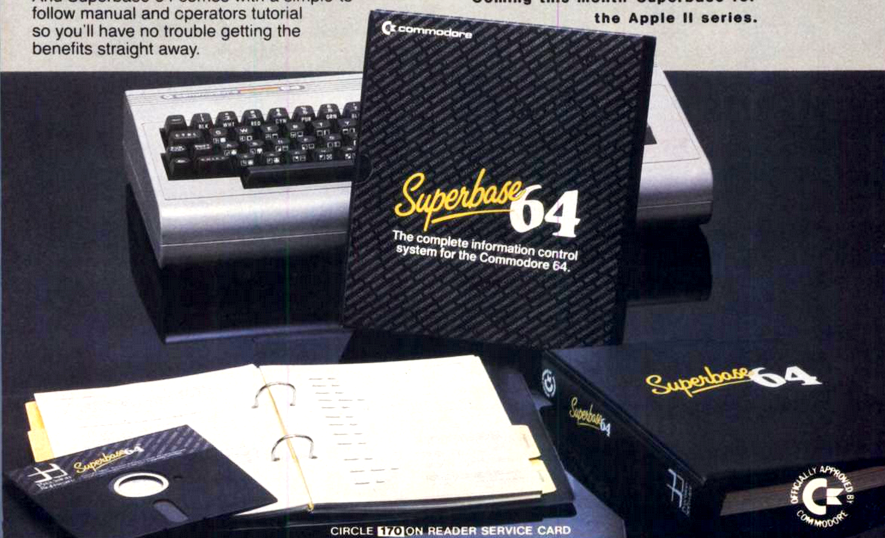

Superbase on the Commodore 64

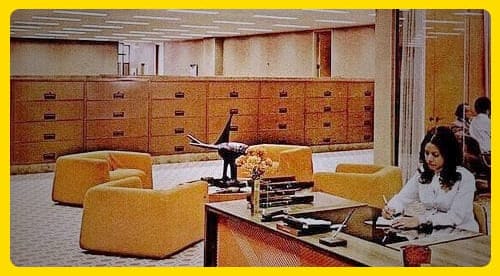

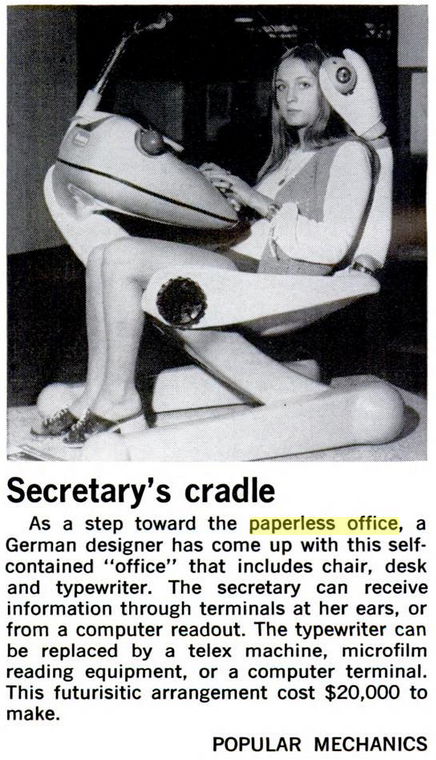

Into the 80s, the promise of a "paperless office" sat always out of reach, but definitely almost here, so long as your office never grows past 1999

When it comes to databases, I've never been much more than a dabbler.

I remember helping dad with PFS:File so he could do mail merge. I remember address books and recipe filers. I once tried committing my comic book collection to ClarisWorks. Regardless of the actual efficacy of those endeavors, working with database management systems never stopped feeling important. I was "getting work done," howsoever illusory it may have been.

These days, the average consumer probably shies away from any kind of hardcore database software. Purpose-built apps which manage specific data (address books, invoicing software) do most of our heavy lifting, and basic spreadsheets (Google Sheets, Notion, Airbase) tend to fill in the remaining niche gaps.

The industry was hell-bent on transforming rapidly improving home computers into productivity powerhouses and database software promised to unlock a chunk of that power. Superbase on the Commodore 64 was itself put to work in forensic medicine in England and to help catch burglars in Florida. Maybe it can help me keep track of who borrowed my VHS copy of Gremlins 2: The New Batch.

Historical Context

My Testing Rig

- VICE v3.9 (64-bit, GTK3) on Windows 11

- x64sc ("cycle-based and pixel-accurate VIC-II emulation")

- drive 8: 1541-II; drive 9: 1581

- model settings: C64C PAL

- printer 4: "IEC device", file system, ASCII, text, device 1 to .out file

- x64sc ("cycle-based and pixel-accurate VIC-II emulation")

- Superbase v3.01 (multi-floppy, 1581-compatible)

Let's Get to Work

The manual has a three-part tutorial, the first two parts of which have an audio component (ripped from cassette tapes). I will absolutely use it for an authentic learning experience. I'm looking forward to some pre-YouTube tutorial content, "What's up everyone, it's ya boy Peter comin' atchu with another Superbase tutorial. If you're enjoying these audio tapes, drop a like on our answering machine and subscribe to AHOY! Magazine."

From first boot, I feel the pain.

After the almost instantaneous launching of trs80gp into Electric Pencil last blog, getting Superbase launched in VICE is annoyingly slow. I appreciate a pedantic pursuit of accuracy as much as anyone, but two full minutes to load Superbase is ridiculous, for my 2025 interests.

Luckily VICE has a "WARP" mode which runs some 1500% faster, bringing boot time to under 10 seconds. A C64 one could only dream of is a keyboard stroke away, to enable or dismiss on a whim. How spoiled we are!

What we talk about when we talk about filing cabinets

Here I am, a businessman of 1983, knitted tie looking sharp with my mullet, ready to thrust my 70s HVAC business into the neon-soaked future of 80s information technology. (The company must pivot or die!) First things first, “What is a database?” I wonder, sipping a New York Seltzer.

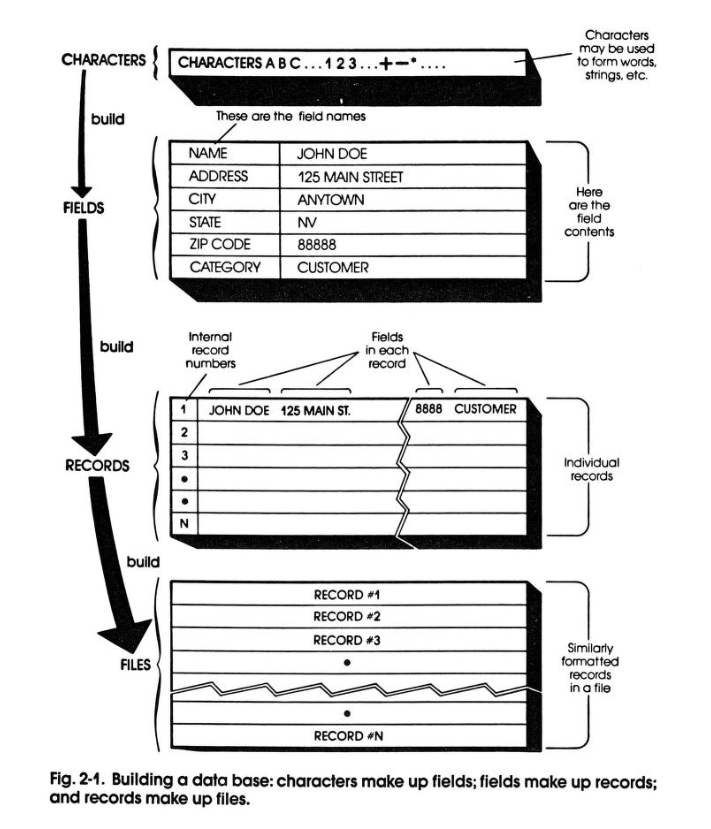

According to the very slow audio tutorial, "It's an electronic filing cabinet!" So far, so good.

"And just as in an ordinary filing cabinet, information is stored in batches called 'files'. and you can think of Superbase as an office containing a number of electronic filing cabinets." OK, so if Superbase is my office, and my office currently contains seven filing cabinets with 150 files/per, I’ll make seven databases to hold my information?

"Superbase will allow you to hold up to 15 files in each database."

OK, I'm not sure I heard that correctly. Rather than having seven cabinets with 150 files each, I instead have 70 cabinets with 15 files each? Is this the "office of the future?"

Come to think of it, are we even using the same definition of the word "file?" When I ask Marlene to bring me "the Doogan file" I receive a file folder filled with Doogan-related stuff: one client, one file.

"Each of the files is made of bits of information known as RECORDS. For example, you may have a file containing names of companies. In that case each company name would be one RECORD." A file which contains only the names of companies?

Now I'm learning that records are made of FIELDS. But we were just told that a RECORD is "a bit of information" like a company name. This filing cabinet metaphor is falling apart and I'm only five minutes into a 60-minute tutorial.

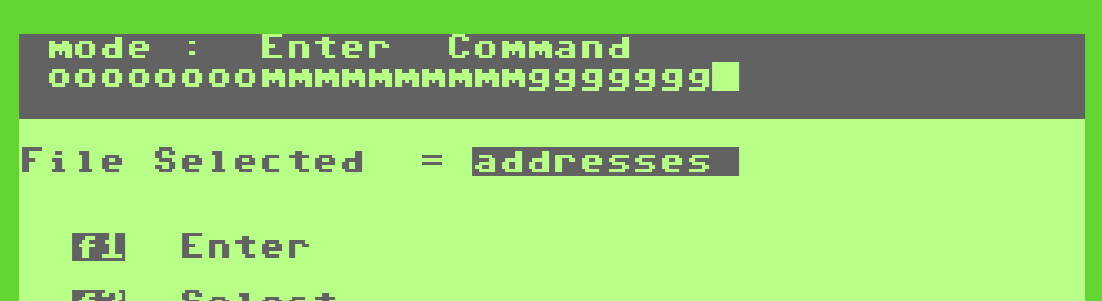

From the manual, "Look at the screen and you'll see the cursor; that's the small flashing square which marks where you are on the screen."

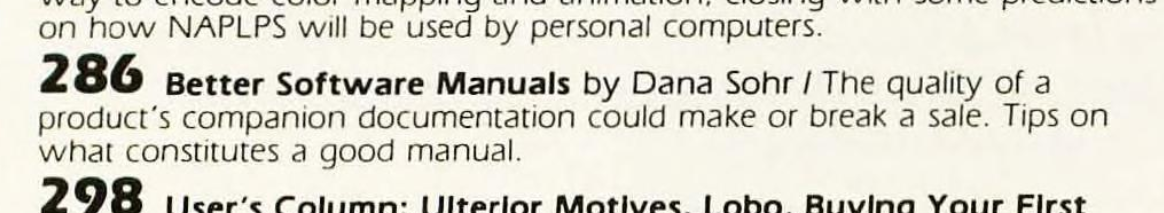

A good manual is hard to find

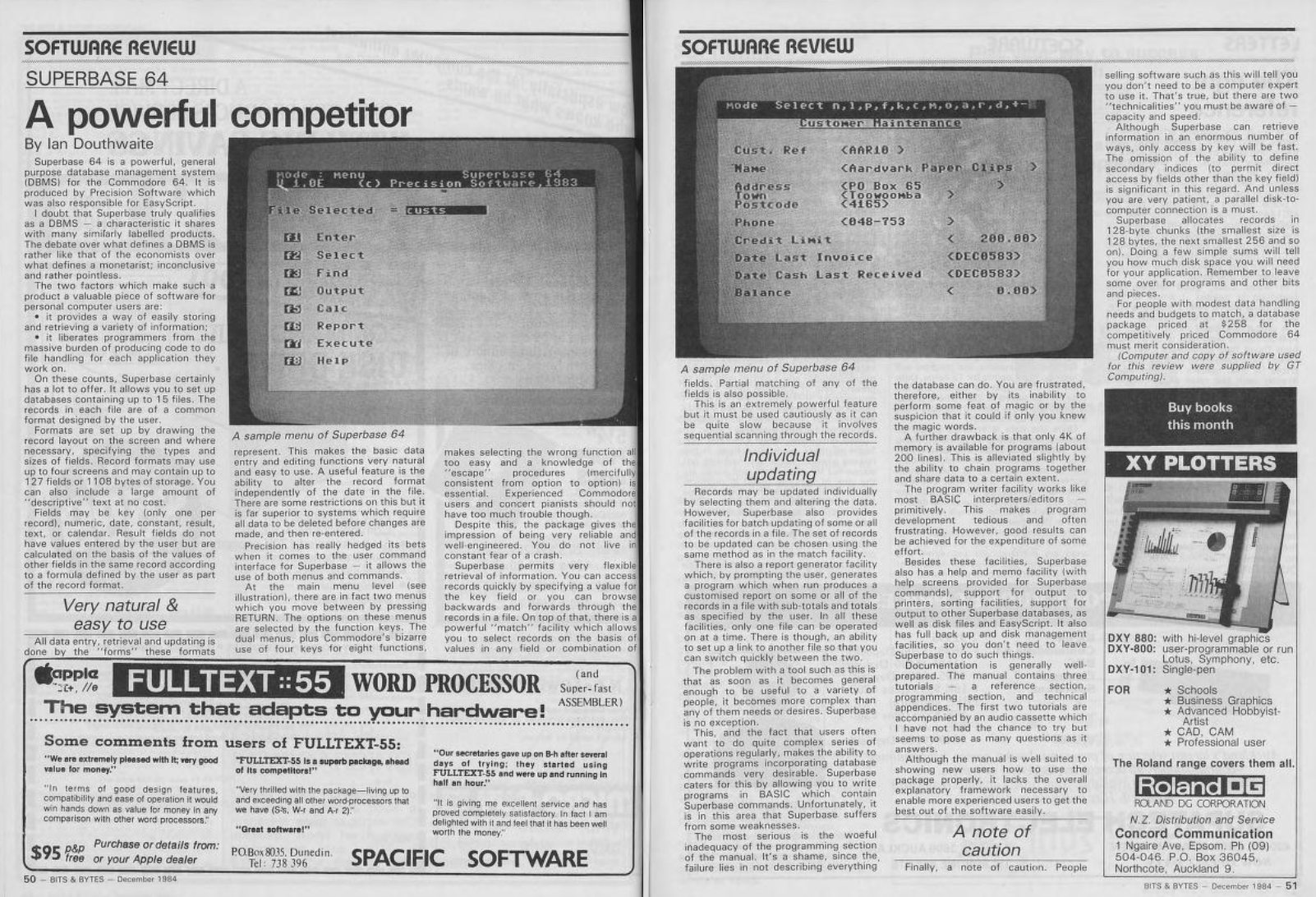

Not only did society have to learn how to create new tools for moving into the information age, we also had to learn how to teach one another how to use those tools. In Superbase's case, I find the manual mostly OK. It offers a glossary, sample code, and a robust rundown of each menu and command.

What's missing here is an explanation of the mental shift required in moving from analog to digital files. Where a traditional filing cabinet is organized by relation, our C64 will discover relations (though this is not a relational database); a kind of inversion of the physical filing cabinet strategy. Without my 2025 understanding of such things, I would be completely lost right now about how Superbase and databases work.

A $5000 phone directory

At any rate, working through the tutorial, I do find the operation of the software quite simple so far. Place the cursor where you want to add a field name or field input area and start typing. F1 and RETURN set the start and end points of a field, which doubles as a visual way to set the length of that field. The field's reference name is only ever the word to the immediate left of the field entry area. Simple, if inflexible.

Setting field types is also easy enough, even if the purpose and usage of the "key" field is never made explicitly clear. It is only ever described as being the field that records will be sorted on by default. Guidance on choosing an appropriate key field and how to format it is essentially nonexistant.

Querying records is straightforward, though there is definitely a learning curve. Partials, wildcards, absence of a value, value sets and ranges, and comparatives (values <100, for example) are all possible and chainable. The syntax is relatively clear, even if conventions (?? is the wildcard token) have subtly changed.

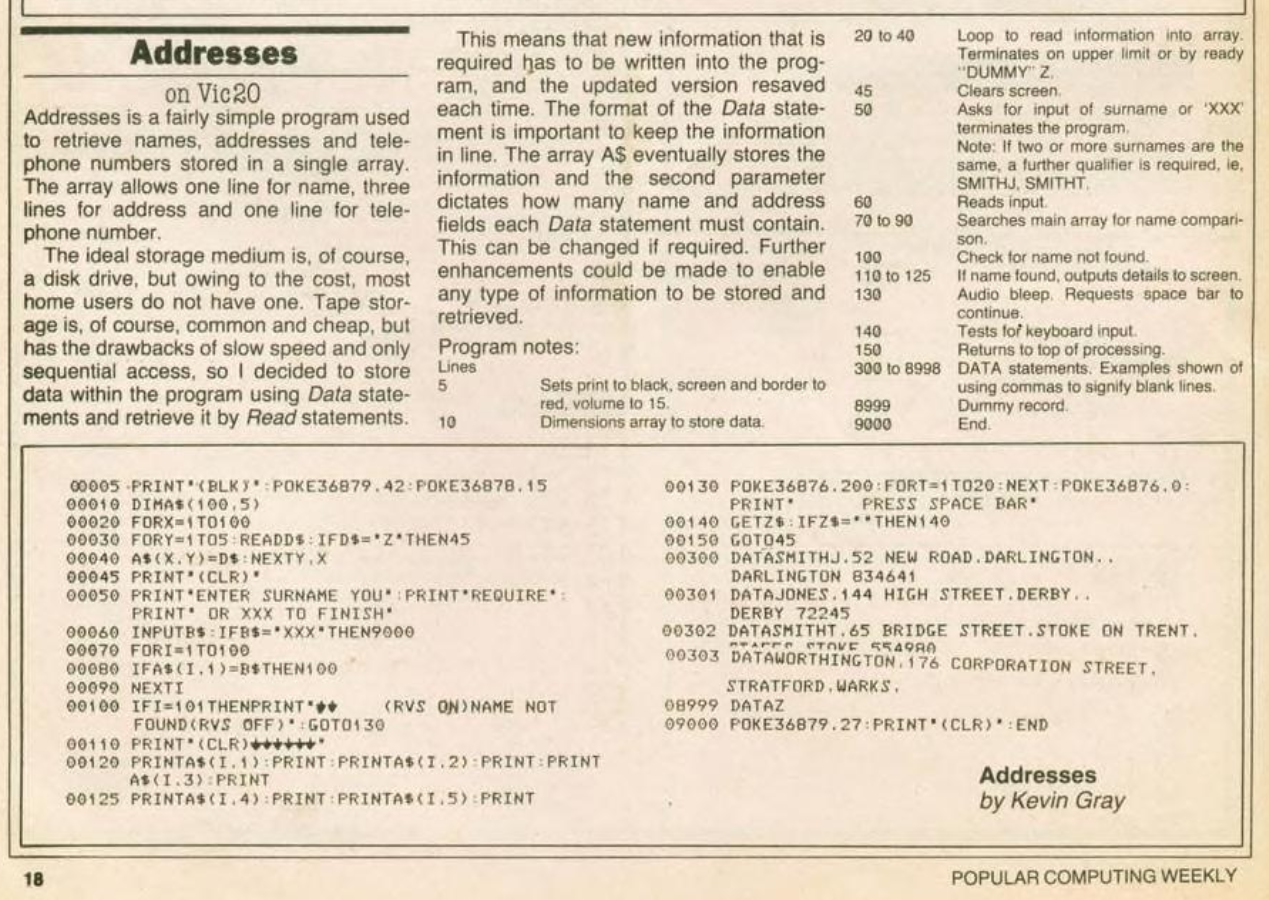

I've now built something like a phone book and entered some sample data. This usage of the database matches my mental model of the object being replaced and I'm feeling somewhat confident. But this is also something I could have built with a type-in BASIC program from Popular Computing Weekly.

If I put myself in the mindset of someone reading a contemporary book like Business Systems on the Commodore 64 by Susan Curran and Margaret Norman, it is quite unclear how my filing cabinet data and organizational structure translates to floppy disk. With floppy drives, a printer, and more I have spent almost $5000 (in 2025 money) on this system. For that outlay of cash, am I really asking too much for someone to help guide me into a "paperless office?"

Speaking of which.

Who do we blame for the "paperless office?"

George Pake of Xerox PARC (yes, that Xerox PARC) gave an interview to Businessweek in June 1975 in which he spoke of his vision for a "paperless office." The later spread of that concept into larger circles seems to owe a lot to F.W. Lancaster. In 1978, Lancaster published Toward Paperless Information Systems and spent a full chapter contemplating what a paperless research lab might look like in the year 2000.

Lancaster's vision paralleled a fair amount of what we know today as the internet. To readers of the time it was all brand new conceptually, so he spent a lot of time explaining concepts like "keeping a journal on the computer" and how databases could just as easily be located 5000 miles away as 5 feet away. He couldn't quite envision high resolution video displays, and expected graphic data to remain in microfilm/fiche. He could envision "pay as you go" for data access, however.

What even is a "paperless office?"

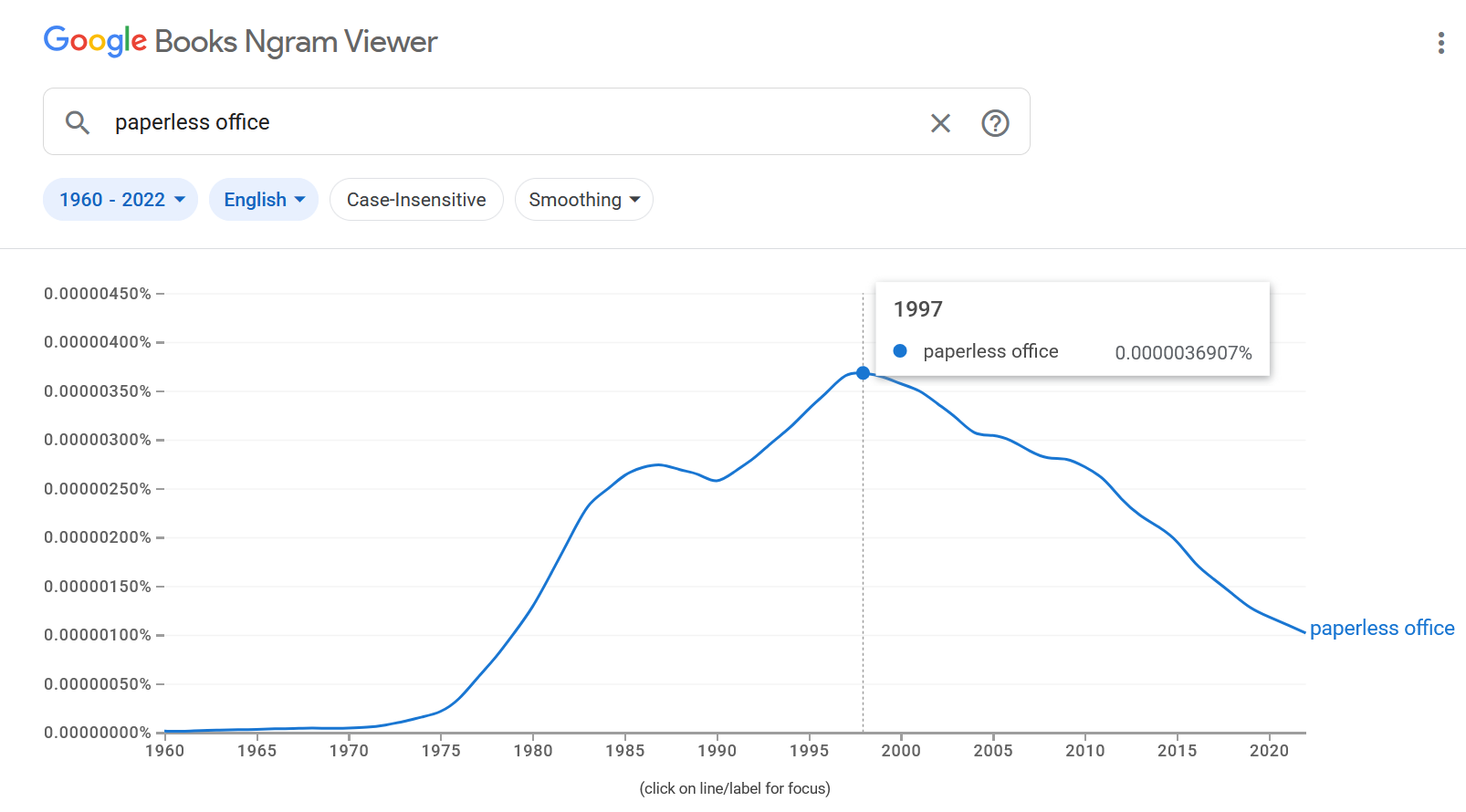

It should be noted that the phrase "paperless office" does not appear in Lancaster's book (it does in his previous book). That phrase had already started an upward trend since before the Pake interview, but in my research it does seem that Lancaster really helped mainstream the concept.

Lancaster identified three main functions of computer use in a paperless office.

- Create information

- Transmit information

- Receive information

Especially in the 80s, transmit and receive were a long way from being cheap and ubiquitous enough to replace paper between two parties. That sounds obvious, but hype around the "paperless office" made it easy to overlook such flaws. Besides, wasn't it a matter of time before the flaws were resolved? Wasn't everyone working toward the same paperless vision?

Well that's hard to say, given the slightly mixed messaging of the time. 1983's The Work Revolution by Gail Garfield Schwartz PhD and William Neikirk says explicitly, "we are at the brink of the paperless office." 1982's The Word Processing Handbook by Russell Allen Stultz cautions us, "The notion of a 'paperless office' is just that, a notion." But May 1983's Compute Magazine keeps the dream alive with a multi-page article, "VICSTATION: A Paperless Office" as though it had already arrived and was waiting for you to catch up.

Computer magazines and academic investigations were typically cold on the idea of the "paperless office" ever coming to fruition. Rather they saw (quite correctly) that if everyone had simple, easy-to-use publishing tools at their fingertips paper usage would increase. The mainstream, ever one to latch onto a snappy catch phrase, really did seem to push the idea to the masses as an inevitability.

- "Ultimately, the workstation configuration will probably replace the usual office furnishings as the organization evolves toward the 'paperless office'"

- The Office of the Future, Ronald P. Uhlig, 1979 - "Transformation of the office into a paperless world began in the early 1980s. Computers have been an integral component of the paperless office concept."

- OMNI Future Almanac, 1982 - "This information revolution is transforming society through basic changes in our jobs and lifestyles. Indeed, the paperless office of the future and computerized home communications centers are information age miracles not to be hoped for, but expected."

- America Wants to Know: The Issues and the Answers of the Eighties, George Horace Gallup, 1983

A CEO in 1983 really couldn't be blamed for buying into the hype. To not have bought into it would have felt tantamount to corporate negligence. I asked ChatGPT for a modern parallel and all it said was, "Time is a flat circle."

You, alright?! I learned it by watching YOU!

Building out anything more advanced than the most rudimentary of rolodexes required a lot of patience and forbidden knowledge. As noted earlier, the manual only gets you so far. There was a decent stream of books published during the early 80s which tried to fill various knowledge gaps. Some would tackle general "using your computer for business" while others would target specific software + hardware combinations.

Database Management for the Apple from 1983, the release year for Superbase, has some great illustrations and explanations about databases and how they work conceptually. It digs into how to mentally adjust your thinking from manual filing to electronic filing. It also includes fully commented source code in BASIC for an entire database program. A bargain for $12.95 ($40 in 2025), but probably ignored by C64 Superbase users?

Unfortunately for us in 1983, the book we Superbase users desperately need won't be published for three more years.

Superbase: The Book, by Dr. Bruce Hunt, was published by Precision Software Ltd, the very makers of Superbase itself in 1986 for $15.95 ($47 in 2025). It straight up acknowledges the lack of help over the years in making the most of Superbase.

"Since Superbase 64 was first released in 1983 there have been many requests for a 'Book of the Program'. We have been promising one for almost as long... However, at last, here it is, a book which although it cannot lay claim to being definitive, has at least the merit of filling a gap."

"Part I: Setting Up a System" addresses almost every single thing I complained about in the tutorial. It contains a mea culpa for failing to help users build anything beyond the most rudimentary of address books.

"Many people...have designed their systems in such a way that (the) powerful features cannot be used. (We) receive many a plea for help. The following pages try to remedy this situation."

It then moves into "the most important discussion in the book." A conceptual framework for thinking about your existing files, and how to translate them into data that leverages Superbase's power, is well explained with concrete examples. As well, it works diligently to show you that the way files and fields were set up in the tutorials that shipped with Superbase was woefully inadequate for making good use of Superbase. We learned it by watching you!

As an example, what was just "firstname" and "lastname" fields in the tutorial are considered here more thoroughly. We are given a proper mental context for why a name is more complex than it first looks. As data, it is better broken into at least five fields: title, initials, first name, surname, suffix. Heck, I'd throw "middle" in the mix as well.

Then Dr. Hunt explains what is actually a very powerful idea: record fields don't have to exist exclusively for human-readable output purposes. That is true, and almost counter to the shallow ways fields are treated in the manual, which only ever seemed to consider field data as output to the screen or a printer.

"The crucial realization is that you don't need to restrict the fields in the record to the ones that will be printed." Many examples of private data that you might want to attach to a customer record (for example) are given, as well as ways to use fields solely for the purpose of increasing the flexibility of Superbase's query tools.

Lastly, in what felt like the book had thoroughly invaded my mind and read my thoughts directly, an entire section is devoted to understanding key values, how they work, and ideas for generating robust, flexible keys. The remainder of the book continues on in the same fashion, providing straightforward explanations and solutions to common user issues and confusions.

It's a solid B+ effort, even if the Apple database book feels more friendly and carefully designed. I'd give this book an A had Precision Software not made its customers wait three years for it.

A villain returns!

Here in 2025, the further into the tutorial I delve, the more the word "deal-breaker" comes up. I'll start with the format of the "Date" field type, and maybe you can spot the problem? We can enter the date in two ways:

- ddMMMyy

- MMMddyy

yy means a two-digit year and ONLY two-digits. This restricts our range of possible years to 1900 - 1999. That's right, returning after a 30 year absence: it's the Y2K problem!

Not only does this prevent us from bringing Superbase into the future, but we also cannot log even the recent (relative to 1983) historical past. I had a great-grandmother alive at that time who was born in the late 1800s, yet Superbase cannot calculate her age.

Moving on, a feature I enjoy in modern databases (or at least more sophisticated than Superbase) is input validation. Being able to standardize certain field data against a master file, to ensure data consistency, would be really nice.

It's also a bit of a drag that a record's key value can only ever be a text string, even if you only use numbers. The manual gives a specific workaround for this issue which is to pad a number string with leading zeros. This basically equates to no auto-increment for you.

With great power comes great wait times

Something I very much appreciate is that the entire program can be run strictly through textual commands; no F-keys or menus necessary. In fact, I dare say the menus hide the true power of the system, functioning as a "beginner's mode" where the user is expected to graduate to command-line "expert mode" later. Personally, I say just jump straight into expert mode.

We can use a [field_name] convention in a command to read and write values from records. BASIC-style variables can store those values for further processing inside longer, complex commands. As a developer, I'm happy. As a non-developer, this would be an utter brick wall of complexity for which I'd probably hire an expert to help me build a bespoke database solution.

"Batch" is similar to "Calc" (itself a free-form or record-specific calculator) which works across a set of records. We can perform a query, store the result as a "list," then "Batch" perform actions or calculations on every record in that list. Very useful, but it comes with a note.

Superbase takes a while to work its way through all the records

"Takes a while" is just south of an outright lie. I must remember that this represents many users' first transition to electronic file management. Anything faster than doing work by hand had already paid for itself; that's true even today.

That said, consider this. I ran "Batch" on eight (8!) records to read a specific numeric field, reduce that value by 10%, then write that new, lower value back into each record.

- Base C64: 1 minute, 6.88 seconds

- In WARP: 6.22 seconds

Now, further consider that a C64 floppy can hold about 500 records, which seems like a perfectly reasonable amount of data for a business to want to process.

- Base C64: 1.25 hours

- In WARP: 6 minutes

ONE AND A QUARTER HOURS! Look, I know it was magical to type a command, hit a button, and have tedious work done while you took a long lunch. I once tasked a Macintosh to a 48-hour render in Infini-D. Here in 2025, I'm balking even at the 6 minute best case scenario in VICE. On real hardware, we must also heed the advice from the book Business Systems on the Commodore 64:

One well-known problem with the machine is its tendency to overheat. It is not designed to be run all day, every day, as are conventional business computers, and if the computer is kept on for long periods overheating may well occur.

Building a better Superbase

In fairness, most of the things I'd want to do are simple lookups and record updates from time to time. Were I stuck on 1982 hardware, it would be possible to mitigate the slow processing by working processing-time into my weekly work schedule. I wouldn't necessarily be "happy" about that situation, and may even start to question my investment if that were the end of the features.

Luckily, Superbase offers a killer feature which offsets the speed issue: programmability. The commands we've been using so far are in reality one-line BASIC programs, and more complex, proper programs can be authored in the "Prog" menu.

We are now unbound, limited only by our knowledge of BASIC (so I'm quite limited) to extend the program, and work around the "deal-breakers" I encountered earlier. Not every standard BASIC command is available (we can't do graphics, for example), but 40 of the heavy hitters are here plus 50 Superbase-specific additions.

I don't want to sound naive, but I was shocked at the depth and robustness, yes even the inclusion of its programming language. It's far more forward thinking than I expected for $99 on a 64K machine. But I also cannot credit the manual with giving too much help with these functions. It's quite bare-bones.

After all is said and done, the simple form building and robust search tools have won me over, but the limitations are frustrating. Whether I could make this any kind of a daily driver depends on what I can make of the programmability. It's asking a lot of me to become proficient in BASIC here in 2025.

But the journey is its own reward. I press onward.

Dropped table

Initially I thought I would build a database of productivity software for the Commodore 64, inspired by Lemon64. The truth is, after my training to-date I am still a fair distance from accomplishing that, though I can visualize a path to success.

There are two main issues I need to solve within the confines of Superbase's tools and limitations. Doing so will give more confidence that it is still useful for projects of humble sizes.

- I want to constrain some data to a standardized set of fixed values.

- I want to solve the Y2K problem.

Make a list, check it twice

Thinking of a Lemon64-alike, to constrain the software "genre" field (for example), I need a master list against which to validate my input. Superbase has some interesting commands that appear to do cross-file lookups:

setlink: select a second file in the same database only whose records you want to look up (no cross-database lookups)link: specify the specific field in the file against which you want to do lookupsrlink: close the link to the second fileelink: "reverse" the linked files; the linked becomes primary and vice versa

The code examples are not particularly instructive, at least not for what I want to do. The linking feature needs a lot more careful attention and practice to leverage.

Rethinking my approach to the problem of data conformity, I have come to realize that the answer was right in front of me. All I really need is the humble checkbox.

There is no such UI element on a machine which pre-dates the Macintosh nor has a GUI operating system, but I can mimic one with a list of genre field names each of a single-character field length. Type anything into a corresponding field to designate that genre. When doing a query for genre, I can search for records whose matching field is "not empty." Faking it is A-OK in my book.

Solving Y2K in Y2K25 like its Y1K983

Without a working date solution, my options for using Superbase in 2025 are restricted. I can either only track things from the 20th century, or only track things that don't need dates. Neither is ideal.

Working on UNIX-based systems professionally all day long, I think it would be nice to get this C64 on board the "epoch time" train. Date representation as a sequential integer feels like a good solution. It would allow me to do easy chronologically sorting, do calendar math trivially, and standardize my data with the modern world.

However, the C64's signed integers don't have the numeric precision to handle epoch time's per-second precision. A "big numbers" solution could overcome this, but that is a heavy way just to track the year 2000. If I limit myself to per-day precision (ignoring timezones, ahem), that would cover me from 1970 - 2059. Not bad!

I poked around looking for pre-existing BASIC solutions to the Y2K problem and came up empty-handed. Hopping into Pico-8 (my programming sketchpad of choice) I roughed out my idea as a proof of concept. Then, after many "How do I fill an array with data in BASIC?" simpleton questions answered by blogs, forum posts, and wikis I converted my Lua into a couple of BASIC routines which do successfully generate an epoch date from YYYY and back again.

2020 if isleap=0 then yd=yd+1

2030 return

2999 REM the epoch calculation, includes leap year adjustments

3000 ty=y-1900

3010 p1 = int((ty-70)*365)

3020 p2 = int((ty-69)/4)

3030 p3 = int((ty-1)/100)

3040 p4 = int((ty+299)/400)

3050 ep=yd+p1+p2-p3+p4-1

3060 return

4999 REM days passed tally for subroutine at 2000

5000 data 0,31,59,90,120,151Snippet from my date <-> epoch converter routines; now it's 2059's Chris's problem.

Click here only if you're REALLY into BASIC...

1 REM human yyyy mm dd to epoch day format

5 REM set up our globals and arrays

10 y=2025:m=8:d=29

11 isleap=0:yd=0:ep=0

15 dim dc%(12)

16 for i=1 to 12

17 read dc%(i)

18 next

99 REM this is the program proper, just a sequence of subroutines

100 gosub 1000

200 gosub 2000

300 gosub 3000

400 print "epoch: ";ep

900 end

999 REM is the current year (y) a leap year or not? 0=yes, 1=no

1000 if y-(int(y/4)*4) >0 then leap=1:goto 1250

1050 leap=0

1100 if y-(int(y/100)*100) > 0 then goto 1250

1150 leap=1

1200 if y-(int(y/400)*400) = 0 then leap=0

1250 isleap = leap

1300 return

1999 REM calculate number of days that have passed in the current year

2000 yd = dc%(m)

2010 yd= yd+ d

2020 if isleap=0 then yd=yd+1

2030 return

2999 REM the epoch calculation, includes leap year adjustments

3000 ty=y-1900

3010 p1 = int((ty-70)*365)

3020 p2 = int((ty-69)/4)

3030 p3 = int((ty-1)/100)

3040 p4 = int((ty+299)/400)

3050 ep=yd+p1+p2-p3+p4-1

3060 return

4999 REM days passed tally for subroutine at 2000

5000 data 0,31,59,90,120,151

5001 data 181,212,243,273,304,334

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

5 REM epoch date back to human readable format

10 y=0:m=0:d=0

11 isleap=0:yd=0:ep=20329

15 dim md%(12)

16 for i=1 to 12

17 read md%(i)

18 next

100 gosub 2000

200 print y, m, d

900 end

999 REM is the current year (y) a leap year or not? 0=yes, 1=no

1000 if y-(int(y/4)*4) >0 then leap=1:goto 1250

1050 leap=0

1100 if y-(int(y/100)*100) > 0 then goto 1250

1150 leap=1

1200 if y-(int(y/400)*400) = 0 then leap=0

1250 isleap = leap

1300 return

1999 REM add days to 1970 Jan 1 counting up until we reach our epoch (ep) target

2000 y=1970:dy=0:td=ep

2049 REM ---- get the year

2050 gosub 1000

2100 if isleap=0 then dy=366

2200 if isleap>0 then dy=365

2300 if td>dy or td=dy then td=td-dy:y=y+1:goto 2050

2399 REM ---- get the month

2400 m=1:dm=0

2500 dm=md%(m)

2700 if m=2 and isleap=0 then dm=dm+1

2800 if td>dm or td=dm then td=td-dm:m=m+1:goto 2500

2899 REM add in the remaining days, +1 because calendars start day 1, not 0

2900 d=td+1

3000 return

4999 REM days-per-month lookup array data

5000 data 31,28,31,30,31,30

5001 data 31,31,30,31,30,31

Maybe, kinda, sorta good enough-ish?

I'm hedging here as I've had a kind of up-and-down experience with the software. I have the absolute luxury of having the fastest, most tricked out, most infinite storage of any C64 that ever existed in 1983. Likewise, I possess time travel abilities, plucking articles and books from "the future" to solve my problems. I have it made.

There are limitations to be sure, starting with the 40-column display. But I also find the limitations kind of liberating? I can't do anything and everything, so I have to focus and zero in on what data is truly important and how to store that data efficiently. The form layout tools are as simplistic as it gets, which also means I can't spend hours fiddling with layouts.

Even if the manual let me down, the intention behind its design unlocks a vast untapped power in a Commodore 64. It's almost magical how much it can do with so little. I can easily see why it won over so many reviewers back in the day.

Though the cost and complexity would have frustrated me back in the day, in the here and now with the resources available to me, it could possibly meet my needs for a basic, occasional, nuts-and-bolts database. It would require learning a fair bit more BASIC to really do genuinely useful things, but overall it's pretty good!

Sharpening the Stone

Ways to improve the experience, notable deficiencies, workarounds, and notes about incorporating the software into modern workflows (if possible).

Emulator Improvements

While Warp mode in VICE is very handy, it's only truly useful when I hit slowness due to disk access. I'm sure I'll find more activities that benefit as this blog progresses, but for text-input based productivity tools, warp mode also warps the keyboard input. Utterly unusable.

Basically I just use the system at normal speed. When I commit to a long-term action like loading the database, sorting, or something, I temporarily warp until I get feedback that the process is complete.

Superbase The Book tells us that realistically a floppy will accommodate about 480 records. However, 1Mb and 10Mb hard drives are apparently supported, so storage should be fine with a proper VICE setup.

Troubleshooting

- Key input repeating like the system is demon possessed? Warp mode is probably still on.

- A snapshot saves the C64 state, but not the emulator state. So if you have a disk in the drive when you take a snapshot, that disk will not be inserted when you restore state. Save your snapshot with a name that reminds you which diskette should be inserted in which drive to continue smoothly from the snapshot.

Getting Your Data into the Real World

- Superbase developers understood that data migration and interoperability are critical. We cannot have our data locked down into a proprietary format with no option to move to a different system. Print and Export accept formatting parameters which allow us to effectively duplicate CSV format.

- Printing with VICE generates an ASCII file. Exporting puts the data onto our virtual disk image. To get data off that disk image into our host operating system, we need to be able to browse disk contents and extract files.

- On Windows, DirMaster works nicely.

- For macOS and Linux, the DirMaster dev created dm, a command-line utility for browsing and working with C64 disk image files.

What's Lacking?

- Speed. I'm spoiled, I admit it. For standard searches it's snappy enough, but batch operations are tedious.

- Superbase isn't particularly easy to use with multiple floppies. The manual addendum for v3.01 says that a two-drive setup is supported, but I didn't really see how to do that. The initial data disk formatting routine offered no opportunity to point to drive #9, for example.

- I wish VICE would show the name of each .d64 file currently inserted into the virtual floppy drives.

- It's a little tough not having access to modern GUI elements in the form builder, like pull-down menus.

- "Build Your Own" is a powerful, flexible, time-consuming process using Superbase's programming tools. Getting around limitations of the pre-built fields, forms, etc seems possible with enough BASIC knowledge, time, and desire to commit to Superbase. Once that data is in there, it's honestly easier to let it stay there than try to work out some export/import function. This may be an issue for your use case.

From the Archives